Fox News Flash top headlines for April 26

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

The Supreme Court Tuesday heard arguments over whether or not the Biden administration can properly do away with the Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), commonly known as the "remain in Mexico" policy, which allowed the U.S. to send migrants back over the border to await immigration hearings.

The crux of the case is whether the federal government can use discretion in carrying out the program, or if, as Texas and Missouri are arguing in their lawsuit, the policy is needed to comply with federal law that says migrants cannot be released into the U.S. because the country lacks resources to detain everyone.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar argued against the idea that the remain in Mexico policy was needed to follow the law.

Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt talks to reporters with Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton after the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in their case about Title 42 on April 26, 2022 in Washington, D.C. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

"On this reading, every presidential administration in an unbroken line for the past quarter century has been in open violation of the [Immigration and Nationality Act]," she said, adding that "if Congress wanted to mandate those results, it would have spoken clearly."

Much of the talk during arguments dealt with statutory language. Prelogar pointed to 8 U.S.C. 1225(b)(2)(c), which says that the attorney general "may return" aliens from contiguous territory back to that territory while they await a hearing, which Prelogar argued was "not a mandate."

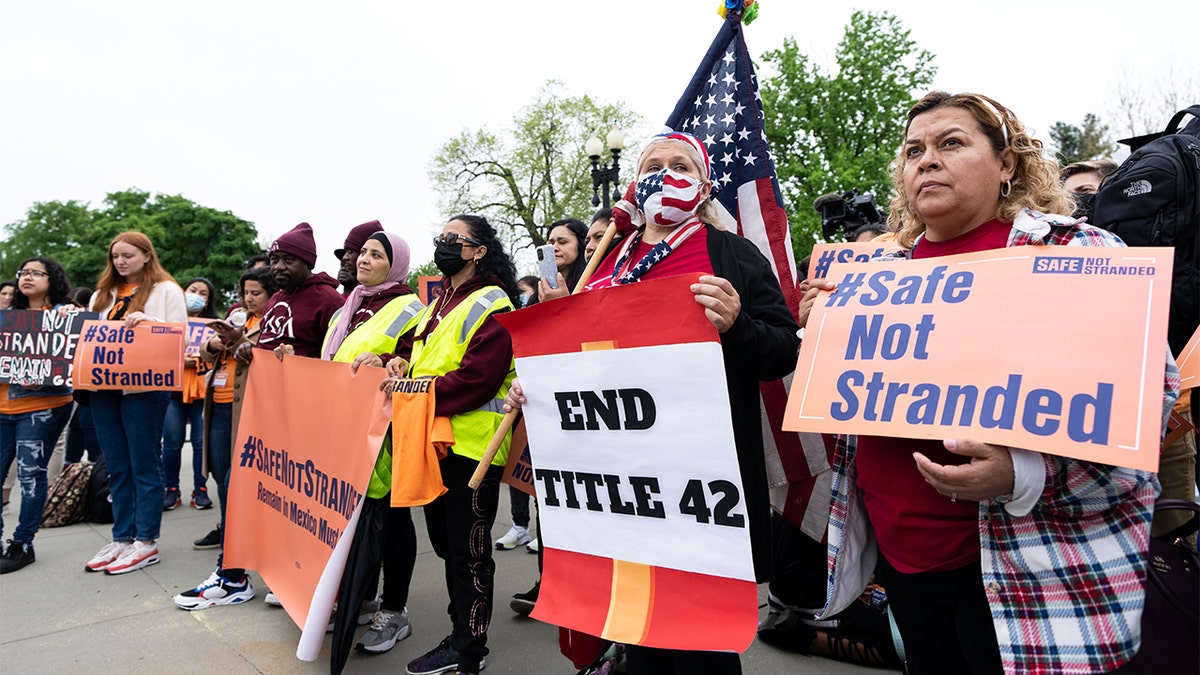

Immigration activists demonstrate in front of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington on Tuesday, April 26, 2022, as the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in the Biden v. Texas case. (Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

Justice Clarence Thomas was quick to point to an earlier part of the statute, 8 U.S.C. 1225(b)(2)(a), which says that if an immigration officer determines that a migrant "is not clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to be admitted" to the U.S., the migrant "shall be detained."

SUPREME COURT AGREES TO HEAR APPEAL FROM TEXAS DEATH ROW INMATE RODNEY REED

"The ‘shall,’ I think, they see as a baseline and then the others are—there’s limited discretion to parole or to do other things," Thomas said in reference to Texas, Missouri, and other states that are fighting to keep the policy. "It seems as though they think discretion is consumed by the ‘shall.’"

The parole and "other things," are discussed in 8 U.S.C. 1226(a), which says that in a case where a migrant is arrested and faces possible removal, the government has three options where they "may" detain them or release them on bail or parole.

Immigration activists demonstrate in front of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington on Tuesday, April 26, 2022, as the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in the Biden v. Texas case. (Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

Chief Justice John Roberts addressed the idea of the government not being able to comply with the law.

"If you have a situation where you’re stuck because there’s no way you can comply with the law and deal with the problem there, I’m just wondering why’s that our problem?" he asked.

Prelogar acknowledged that this was not the court’s problem, but that the court need not do anything but look at the lower court’s interpretation of the "may return" language of the statute, which resulted in an injunction keeping the administration from eliminating MPP.

"All the court needs to say in this case is that the contiguous territory return provision does not carry the meaning that justified the district court’s injunction in this case," Prelogar said. Any other question of statutory meaning in other sections do not require the Supreme Court’s attention here, she argued.

Judd Stone of the Texas Attorney General’s office argued before the court that the only ways to satisfy federal requirements regarding migrants: detain them, parole, or return them to the countries they came from.

Justice Thomas, echoing what Prelogar said earlier, asked Stone if "any administration ever complied with 1225 under your reading?"

"I assume not," Stone said. When Thomas asked if it was "odd" for Congress to pass a law that the government could not follow, Stone said no, and that there has been a mandatory detention requirement "for over a century."

If Congress did not provide the resources for an administration to fully comply, it was up to the executive branch "to do the best it can."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The case is being heard at a time when the Biden administration is in the process of reversing another Trump-era immigration border policy, the Title 42 public health order that allows for expedited removal of migrants arriving from countries affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

President Biden said he was lifting Title 42 as of May 23, resulting in a lawsuit from a number of states. On Monday, a federal judge issued a temporary injunction blocking the administration from rescinding the order.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.