Retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor dead at 93

'FOX News Sunday' anchor Shannon Bream joined 'America's Newsroom' to discuss the life and legacy of the retired Supreme Court justice.

Retired Associate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court, has died, the high court announced. She was 93.

O'Connor died Friday morning in Phoenix of complications related to advanced dementia, probably Alzheimer's, and a respiratory illness, the Supreme Court said in a news release.

She is remembered as a history-making woman, a Westerner, a pragmatic conservative, a keen legal mind and a beloved mother and grandmother.

"We all bring with us to the Court or to any task we undertake, our own lifetime of experiences and background," O'Connor told Fox News in a 2003 interview. "My perceptions might be different than some of my colleagues, but at the end of the day, we ought to all be able to agree on some sensible solutions to the problem."

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor is shown before administering the oath of office to members of the Texas Supreme Court in Austin, Texas, on Jan. 6, 2003. (AP Photo/Harry Cabluck)

"Sensible solutions" may best describe how the jurist approached thorny legal questions, and how she carved out her important role as the plain-speaking "swing vote" on the Supreme Court. A pioneer in both her upbringing in the high desert of the Southwest and throughout her professional career, O'Connor stood out from the moment she arrived as the first woman on the nation's highest court.

"She was arguably the most influential woman in the United States," said Edward Lazarus, author of "Closed Chamber: An Inside Account of the Supreme Court." "Her power was hard-earned and completely of her own making."

O'Connor stepped down in 2006 from the bench, but remained an active and public voice for a variety of causes, including judicial independence and civics education. In 2018, the then 88-year-old revealed in a letter released to the public that she was in the early stages of dementia.

The Swing Vote

In a statement, Chief Justice John Roberts praised O'Connor as a history-making justice with a fierce independent streak.

"A daughter of the American Southwest, Sandra Day O’Connor blazed an historic trail as our Nation’s first female Justice. She met that challenge with undaunted determination, indisputable ability, and engaging candor," Roberts said.

"We at the Supreme Court mourn the loss of a beloved colleague, a fiercely independent defender of the rule of law, and an eloquent advocate for civics education. And we celebrate her enduring legacy as a true public servant and patriot."

SANDRA DAY O'CONNOR, FORMER SUPREME COURT JUSTICE, SAYS SHE HAS ‘BEGINNING STAGES OF DEMENTIA’

Supreme Court nominee Sandra Day O'Connor speaks before a Senate hearing on her nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court on Sept. 9, 1981. (AP Photo/ John Duricka)

O'Connor was the first woman to be appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court after she was nominated by President Ronald Reagan in 1981.

A crucial swing vote, O'Connor's power to help tip the balance on important rulings — and thereby shape the law and larger society — was subtly evident, but not lost on her colleagues. "Often you'd see in oral argument that Justice Kennedy and Justice O'Connor were actually being courted by the other justices," said Andrew McBride, a former O'Connor law clerk. "She was often the first justice to pose a question in important court arguments, thereby quickly setting the tone for the back-and-forth debate to follow."

By moderating the conservative Rehnquist court's impact on issues like abortion and affirmative action, O'Connor was long a source of frustration to some Republicans. Her power lay in her judicial philosophy: while O'Connor agreed with the conservative majority most of the time, she frequently wrote her own, more narrow concurrences. That often had the effect of blunting a ruling's impact.

"Her view of judicial restraint led her to produce more moderate, limited, and fact-bound, detailed opinions," said Carolyn Frantz, a former O'Connor law clerk and now a private attorney.

President Ronald Reagan presents his Supreme Court nominee Sandra Day O'Connor to members of the press in the White House Rose Garden in Washington, D.C., on July 15, 1981. (AP Photo)

But her reputation as an independent-thinking moderate drew criticism from both the right and the left. She was accused of watching how other justices voted in closed-door conference before stepping in and placing herself in the "swing-vote" center, thereby tipping the balance to her judicial ideology. Former clerks and other colleagues strongly reject that assertion.

"It was a practical approach, but one that was really grounded in legal principles and respect for what the judiciary means to our form of American democratic government," said Ruth McGregor, O'Connor's first Supreme Court law clerk in 1981, and herself the former chief justice on the Arizona Supreme Court.

SANDRA DAY O'CONOR WAS PROPOSED TO BY LATE SUPREME COURT CHIEF JUSTICE, BIOGRAPHER REVEALS

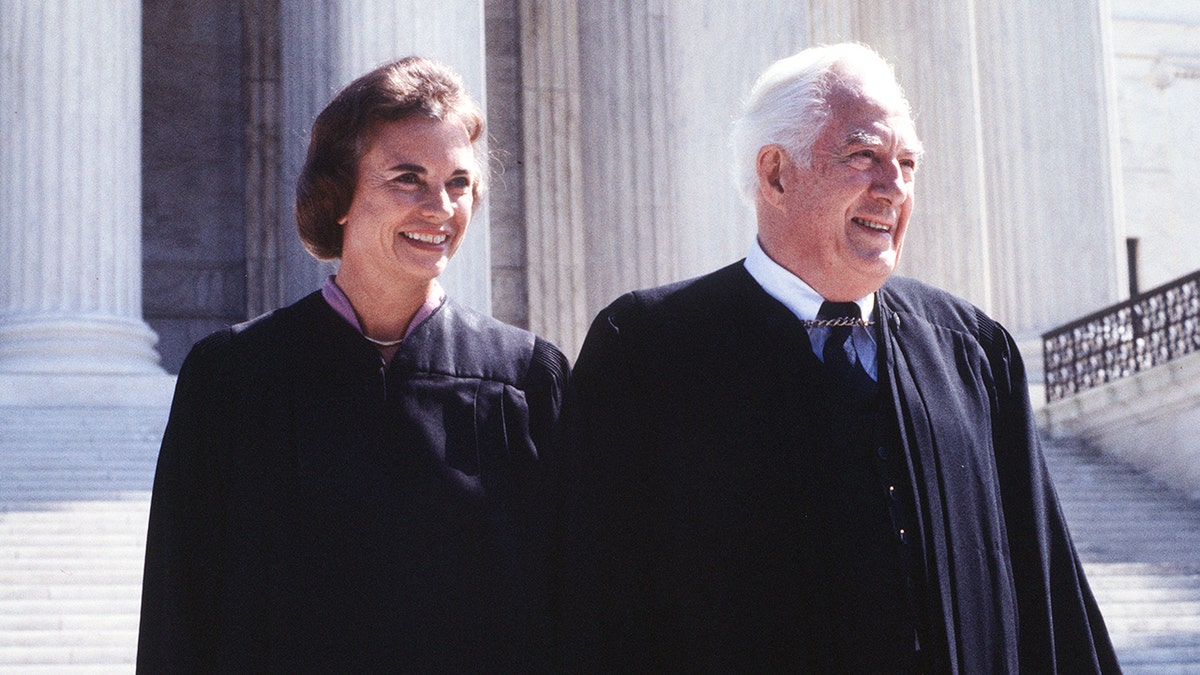

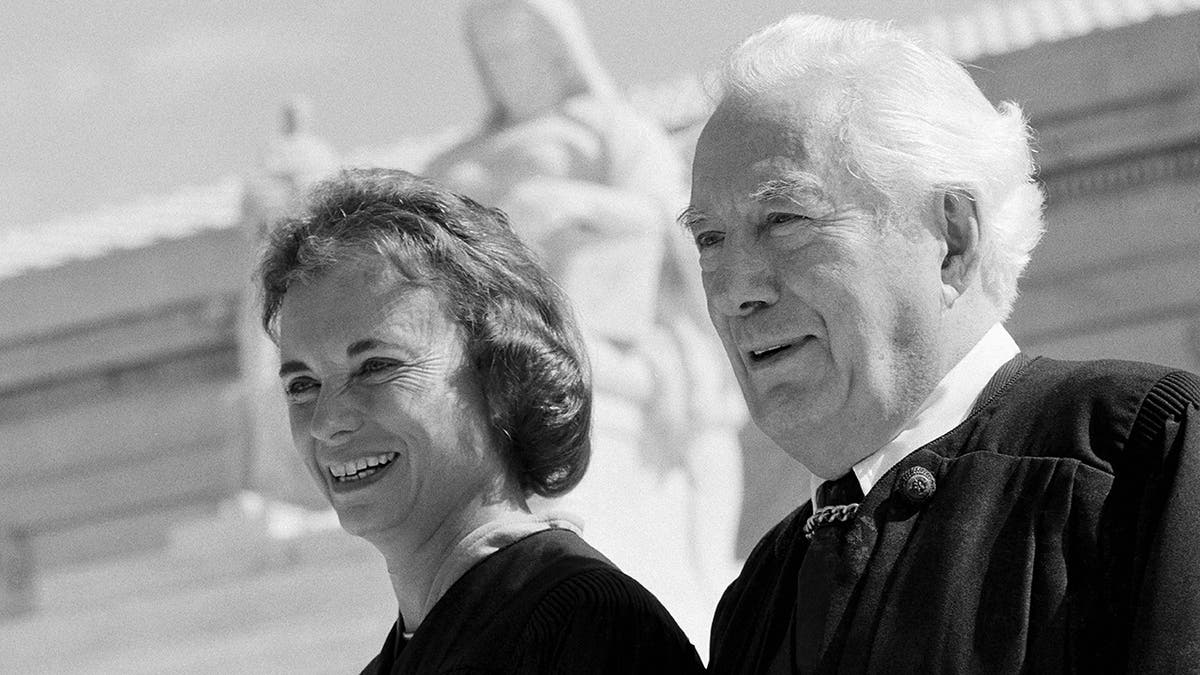

Supreme Court Associate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor poses with Chief Justice Warren Burger after her swearing in at the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 25, 1981. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds)

Some legal scholars also note her rulings lack any over-arching ideology, or a "grand unified theory" to use her phrase, that would provide a judicial roadmap on future laws and cases.

Colleagues contend O'Connor was guided more often than not by a cautious, measured approach to constitutional precedent. "She looked simply at the law, doing as little as she can to satisfy the law, trying to get that right," said Frantz.

That judicial minimalism had its critics. "She didn't give much guidance to other courts in her rulings, there was a lack of consistency, distinctiveness," said legal analyst Lazarus, himself a former Court law clerk. "Often it seems her opinions were too narrow, reflecting only how it strikes just Justice O'Connor, what she personally thought."

Despite that reputation, O'Connor in public remarks asked tough questions about the broader impact laws had on society, involving cases past and future, including the government's response to the war on terror.

Shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks, she spoke about how the country would have to balance national security with long-established individual rights and protections. "Can a society that prides itself on equality before the law treat terrorists differently than ordinary criminals?" O'Connor asked. "And where do we draw the line between them?"

Life on the "Lazy B"

Born in El Paso, Texas, on March 26, 1930, O'Connor was the daughter of Harry Alfred Day, a rancher, and Ada Mae (Wilkey). The details of her early life were lovingly recalled in her 2002 memoir, "The Lazy B," in which O'Connor wrote about life on nearly 200,000 acres of rural Arizona ranchland, 25 miles from the nearest town, living without running water or electricity until she was 7. By then she was roping, riding, and repairing fences with the cowboys, and she knew how to shoot a gun and steer a pickup. She grew up possessed with a strong will, self-reliance and ambition.

Gifted with a brilliant intellect, O'Connor enrolled at Standord University at the age of 16 and graduated magna cum laude with a B.A. in economics in 1950. She went on to receive her law degree from Stanford in 1952.

While at law school, O'Connor served on the Stanford Law Review under its then-editor-in-chief, future Supreme Court chief justice William Rehnquist. He finished first in their class of 102; she, third. The pair dated in 1950 and Rehnquist proposed marriage in 1951, although she ultimately turned down the proposal and broke off the relationship after moving to Washington, D.C. It was one of four proposals she turned down during her time at Stanford before marrying John Jay O'Connor III in 1952.

WHO ARE THE SUPREME COURT JUSTICES?

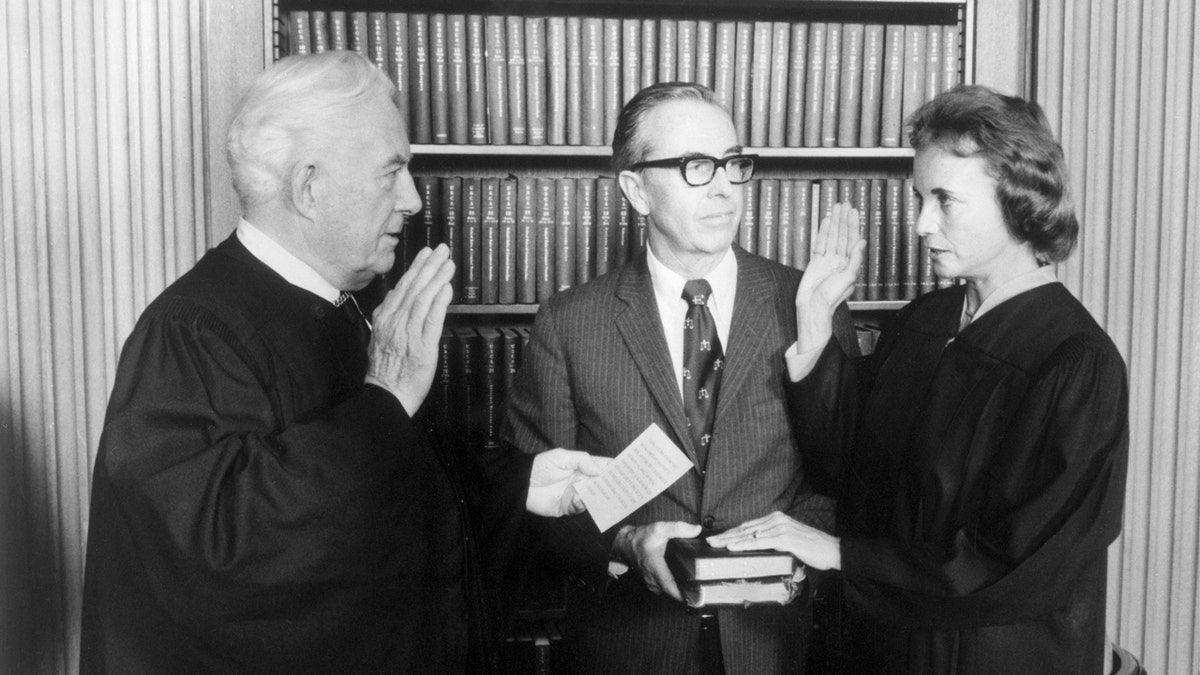

Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the first female justice of the Supreme Court, is sworn in by Chief Justice Warren Burger in the court's conference room in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 25, 1981. Justice O'Connor's husband, John, holds two family Bibles. (AP Photo/The White House, File)

After graduation, the reality of being a woman in the world of law set in. No firm would hire her, except one, which wanted O'Connor only as a legal secretary. She eventually found her way, and her calling, by becoming a deputy county attorney in California. The job "influenced the balance of my life," she recalled, "because it demonstrated how much I did enjoy public service."

Her early career was varied: a civilian lawyer for the U.S. Army in Germany; co-founder of a small law firm; assistant state attorney general in Arizona; state senator, eventually becoming the body's majority leader — the first woman to do so in any state; then election to a state judgeship, and later Arizona's Court of Appeals. She also passed up a chance to run for governor in 1978.

Despite her statewide successes, she had very little national profile. O'Connor and the nation were shocked when President Reagan chose her in July 1981 to fill a high court vacancy, fulfilling a campaign pledge to nominate a woman. Mr. Reagan described her at the time as "truly a person for all seasons, possessing qualities of temperament, fairness, intellectual capacity and devotion to public good."

An Independent Streak

Supreme Court Associate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor poses for a photo in 1982. (AP Photo)

O'Connor, deliberately or not, became the well-known "swing" justice, her moderately conservative views often the deciding factor in close 5-4 votes. She dismissed the label, telling Fox News once, "That's something the media has devised as a means of writing about the Court, and I don't think that has a lot of validity."

The cases where her vote made the difference were long and notable: limiting affirmative action, permitting public aid and vouchers to religious and parochial schools, and in several abortion-related cases, where a woman's reproductive rights were narrowly re-affirmed. Despite criticism from conservatives, O'Connor never backed down from her insistence that states place "no undue burden" on the fundamental right to abortion.

Her concurrences established legal boundaries on several major issues, such as striking down a state-mandated "moment of silence" in schools, and reducing obstacles to capital punishment. And she wrote the 1989 opinion restricting minority set-asides for government contracts. But her nuanced ruling in that case offered significant legal wiggle room, allowing such race-based preferences to correct past discrimination.

ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE WARNING SIGNS AND PREVENTION

In Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), O'Connor agreed with the majority that a city-sponsored nativity scene did not violate the constitutional ban on government support of religion. In doing so, she proposed the "endorsement" test, which established a judicial standard to measure the limits of church-state interaction.

"What is crucial is that a government practice not have the effect of communicating a message of government endorsement or disapproval of religion," she wrote. "It is only practices having that effect, whether intentionally or unintentionally, that make religion relevant, in reality or public perception, to status in the political community."

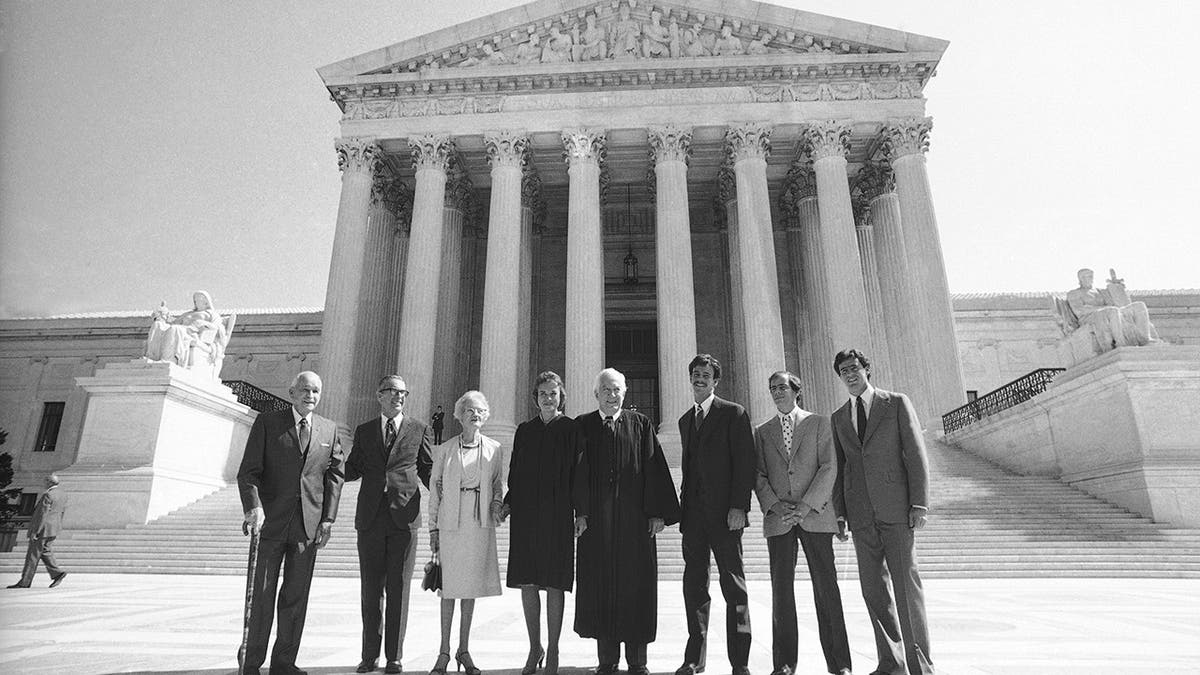

Justice Sandra Day O'Connor poses for photos on the steps of the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., before being sworn in with her family on Sept. 26, 1981. From left are: Justice O'Connor's father, Harry Day; her husband, John J. O'Connor; her mother, Ada Mae Day; O'Connor; Chief Justice Warren Burger; and her sons, Brian, Jay and Scott. (AP Photo/Bob Daugherty)

And she sided with her more conservative colleagues in the Bush v. Gore dispute of 2000. While some legal experts and politicians believe that ruling did not actually decide the election, O'Connor bluntly thought otherwise. In her 2003 book, "Majesty of the Law," she wrote the decision "held unconstitutional Florida's presidential election recount procedures, and thereby determined the outcome of the election."

But O'Connor's independence was evident on several key issues, many involving limits on government power. In Atwater v. City of Lago Vista (2001), she broke from her conservative colleagues, dissenting on a ruling allowing the arrest and brief incarceration of a mother who failed to put seatbelts on her two young children, considered a misdemeanor usually punishable by a fine.

"As the recent debate over racial profiling demonstrates all too clearly, a relatively minor traffic infraction may often serve as an excuse for stopping and harassing an individual," wrote O'Connor. "After today, the arsenal available to any officer extends to a full arrest and the searches permissible concomitant to that arrest. An officer's subjective motivations for making a traffic stop are not relevant considerations in determining the reasonableness of the stop."

A Practical Approach

In court, O'Connor's demeanor was serious, studied, her questions spare and pointed to the practical effect of laws. This exchange from the 2000 Bush v. Gore Florida ballot recount was typical: "Isn't there a big red flag out there [saying] 'watch out'?" she asked Al Gore's lawyer about whether the Florida high court usurped the role of the state legislature when it ordered a new recount to commence.

Privately, friends and colleagues all remembered O'Connor was fun to be around. "She was a great role model both personally and professionally," said Frantz. "She showed me the importance on how to balance all aspects of life. She expected us to work hard, but also cared about us. When I would be there late at night, she might come in and say, 'What are you doing here? You really ought to go home.'"

Sandra Day O'Connor and Chief Justice Warren Burger pose for pictures at the U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 25, 1981. (AP Photo)

O'Connor was known for her intensity, her desire to be in control, and was a stickler for detail.

Colleagues fondly recall a 2003 reunion in Arizona of her former clerks, where O'Connor's people skills shined — remembering all the names of spouses and children of clerks from years past. For them, she organized potluck suppers, ski outings, mandatory trips to museums and musical jam sessions in her chambers with friends and court employees.

Opening Doors

When O'Connor joined the high court bench, women were all but invisible in the frontlines of American law. Just 8% of lawyers then were female, and only 5% were federal judges.

"It's been something that opened so many doors for other women that it really is a joy to know that it did happen," she told us in 2003.

"She shattered the glass ceiling of the judicial branch, an equal branch of power," said Sarah Suggs, president of the O'Connor Institute for American Democracy, founded by the justice in 2006. "Think about how profound that is."

Her toughness and her dry, Western wit were on display when O'Connor was diagnosed in 1988 with breast cancer. She was back on the bench within weeks after treatment, and recalled years later, "The worst was my public visibility, frankly. There was constant media coverage: 'How does she look?' 'When is she gonna step down and give the President another vacancy on the Court?' 'You know, she looks pale to me, I don't give her six months.'"

O'Connor not only survived, but thrived in both life and the law.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

In her 2003 book "The Majesty of the Law," O'Connor wrote an open letter to her granddaughter Courtney, telling her, "A nation's success or failure in achieving democracy is judged in part by how well it responds to those at the bottom and the margins of the social order ... The very problems that democratic change brings — social tension, heightened expectations, political unrest — are also strengths. Discord is a sign of progress afoot; unease is an indication that a society has let go of what it knows and is working out something better and new."

O'Connor is survived by her three sons, Scott (Joanie) O'Connor, Brian (Shawn) O'Connor, and Jay (Heather) O'Connor; six grandchildren: Courtney, Adam, Keely, Weston, Dylan and Luke; and her beloved brother and co-author, Alan Day, Sr. Her husband, John O'connor, preceded her death in 2009.