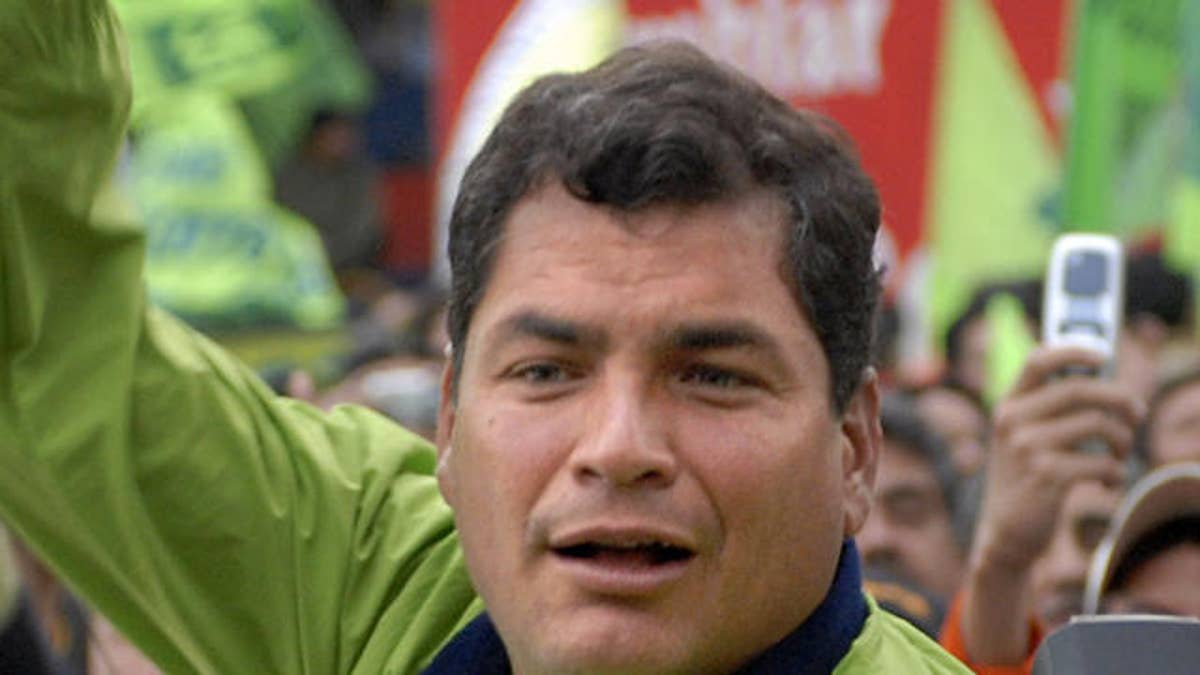

Ecuadorean Presidential candidate Rafael Correa greets supporters during his closing campaign rally in Quito, Ecuador, on Thursday, Oct. 15, 2006. Elections will be on Sunday Oct. 15. (AP Photo/Cecilia Puebla)

It now appears that Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa has won voters’ approval to further consolidate his control over two institutions essential to the functioning of any healthy democracy: a free press and an independent judiciary.

While the vote tallies on the pertinent questions in the May 7th national referendum were no doubt closer than Correa expected, they unfortunately give his latest power grab a patina of legitimacy.

Like Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Correa has viewed a free press as an obstacle to his radical political project that must be defeated. In August 2009, he declared the Ecuadorean press “the biggest adversary with a clear political role, though without any democratic legitimacy.”

It is not just a war of words, either. In December 2010, an elite police unit raided the offices of the Ecuadorean periodical Vanguardia, which had been investigating corruption in the Correa government. Recently, President Correa filed a criminal defamation complaint against a leading daily, El Universo, and several of its officers for column critical of his job performance.

The Correa government has also used tax laws to take over privately owned stations and regularly threatens to shut down others. At last count, the government controlled some twenty media companies, including three popular television stations (accounting at the time for about 40 percent of the country’s nightly news audience) seized from the Isaias Group, a business conglomerate against which Correa has waged a particularly harsh vendetta.

Now, the President is in a position to pull the noose tighter on a free press. Voters approved permission to establish a communications law that would allow the government to strictly regulate media content and even hold individual journalists responsible for any violations.

President Correa also intends to prohibit an owner of any type of outside business from owning a media entity of any sort. This would force a number of the remaining owners of independent media entities to divest themselves from such entities or their other businesses. Clearly, freedom of expression and opposition access to the media will be severely curtailed if Correa has his way.

On the second major issue of the referendum pertaining to the judiciary, President Correa, apparently unsatisfied with the provisions on selecting judges in his own rewritten constitution of 2008, wants to change the rules again. Now, he wants to abolish the Supreme Court and, rather than judges being selected by an independent body, he wants the Executive (himself), Legislative (which his party controls), and the Judicial branches to form a commission on appointing judges.

Given the skewed representation, the new provision will effectively give Correa free rein to name his own judges, further undermining rule of law in Ecuador and placing the courts at the service of the President.

To be sure, Ecuador’s struggle to establish a viable judicial system predates Correa’s administration by years, but it is difficult to see how allowing the Chief Executive such discretion in appointing judges will improve matters in any way.

In addition to their deleterious effects on Ecuadorean democracy, the upheavals in the media and judicial sectors come at a particularly critical point in relation to broader regional security matters.

As Germany’s Deutsche Welle reported last year, as a result of corruption, weak institutions and anti-money laundering laws, and lax anti‐terror financing laws, “Ecuador is emerging as a focus for transnational criminal groups, according to U.S. and European officials. Colombian and Mexican drug traffickers as well as Chinese and African human traffickers use it as a business hub.”

This month, a senior DEA official told Reuters that Ecuador was becoming a “United Nations” of organized crime with drug traffickers of various nationalities establishing bases of operation there. “We have cases of Albanian, Ukrainian, Italian, Chinese organized crime all in Ecuador, all getting their product for distribution to their respective countries,” he said.

An increasingly politicized judiciary and a cowed media are no ways to confront this growing menace.

The gutting of democratic institutions and the undermining of separation of powers are hallmarks of Hugo Chávez’s so-called Bolivarian Alliance, as are the use of referendums to aggrandize power in the presidency and seek perpetual re-election. Correa, Chávez, and Bolivia’s Evo Morales play on the majority of their peoples’ deep-seated desire for change, but can only offer up anachronistic authoritarian solutions that have failed time and time again to benefit anyone but those in power.

It is a cruel hoax being played on populations with legitimate grievances. One hopes that Ecuadorean voters will soon recognize that Correa’s autocratic behavior is no prescription for economic growth, security, or stability. It is also incumbent on the United States not be seen as enabling this destructive process. Instead, the United States should consistently counter the radical populist siren song, speak out against abuses of power and threats to democracy and rule of law, demonstrate solidarity with true Ecuadorean democrats, and emphasize the growing threats to regional security posed by international criminal groups.

Indeed, with Hugo Chávez dominating headlines with his outrageous antics, it is easy to overlook the anti-democratic actions of Rafael Correa. It is time more attention is paid to the steady of erosion of fundamental rights and freedoms occurring today in Ecuador.

José R. Cárdenas served in several foreign policy positions during the George W. Bush administration (2004-2009), including on the National Security Council staff. He is a consultant with Vision Americas in Washington, D.C., and edits the website www.interamericansecuritywatch.com and blogs at http://shadow.foreignpolicy.com/.

Follow us on twitter.com/foxnewslatino

Like us at facebook.com/foxnewslatino