Attempts to drill for oil in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge have for years faced stiff opposition from some groups of Native Alaskans, who consider the land sacrosanct and say drilling would destroy a delicate environment.

But not all indigenous Alaskans think this way. With a Congress and White House that look at drilling more favorably, some Alaska Native corporations are now looking to cash in on any future oil revenues.

The Arctic Slope Regional Corp., the only regional Native corporation that has rights to future oil revenues from the subsurface land it owns beneath ANWR, has demanded that other corporations stop asking Congress to require the company to share any of its oil wealth, according to a letter obtained by the Alaska Dispatch News.

"We also indicated our unhappiness at attempts by a few to re-open a long-resolved issue and attempt to undermine a settlement agreement from years ago,” Ty Hardt, ASRC's director of communications, said in an email to the newspaper. The ASRC represents around 13,000 Iñupiat Eskimo shareholders in northern Alaska.

The Alaska Native Corporations is a group of 12 regional corporations that was established in 1971 when Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, which settled land and financial claims made by the Alaska natives.

In the letter – dated Feb. 10 – the president of Arctic Slope Regional Corp., Rex Rock Sr., asked Bering Straits Native Corp. President Gail Schubert to stop lobbying Congress to pass legislation requiring Rock’s company to share any future oil revenues from ANWR with the other corporations.

Rock’s letter comes at a time of high hopes from the Native Corporations – and Alaska’s congressional delegation – that the four decade-long ban on oil exploration in ANWR will be lifted under President Trump and a Republican-controlled Congress.

Trump’s appointment of Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt to lead the Environmental Protection Agency, Exxon Mobil CEO Rex Tillerson as secretary of state and Montana Rep. Ryan Zinke as Interior Secretary buoyed the hopes of many energy industry insiders and Alaskan lawmakers who have seen attempts to drill the ANWR thwarted during President Obama’s time in office.

"As we work with members of our Congressional delegation to finally conclude more than four decades of effort to authorize a responsible oil and gas program in ANWR, we understand that you are attempting to enlist Congress' assistance in taking private property owned" by ASRC, Rock said in his letter. “ASRC and its shareholders strongly oppose this proposed taking.”

A polar bear sow and two cubs are seen on the Beaufort Sea coast within the 1002 Area of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in this undated handout photo provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Reuters)

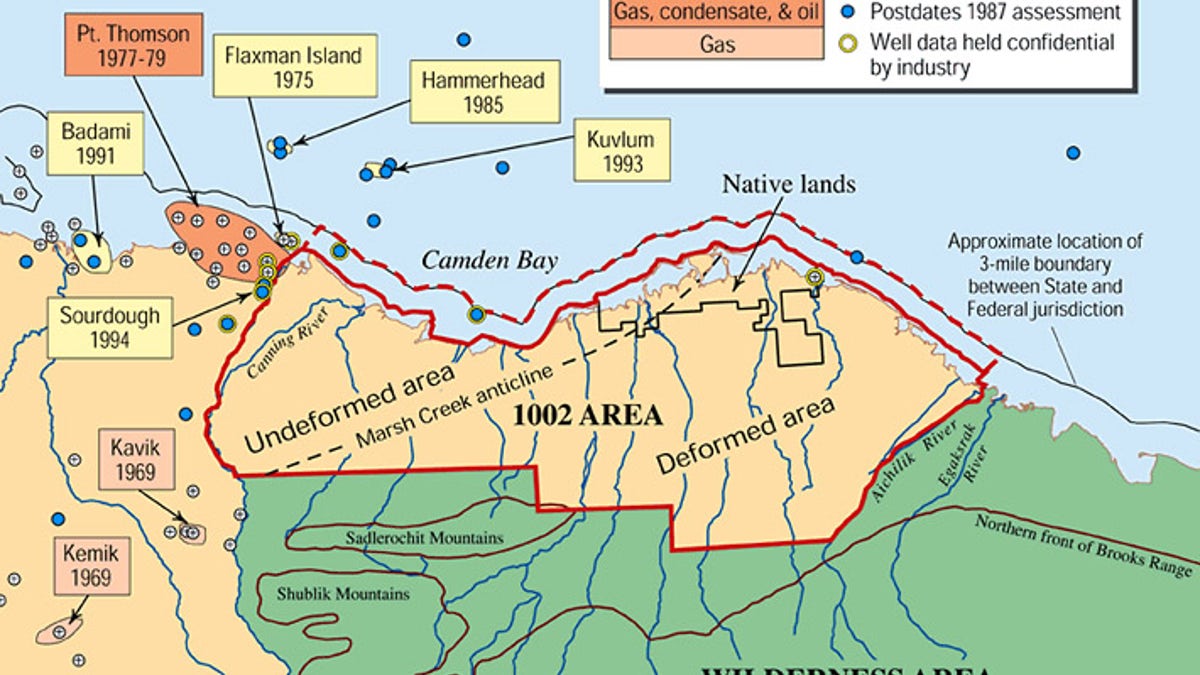

At the heart of the battle over ANWR – a 19 million-acre tract of land flanked by the Brooks Range to the south, the Beaufort Sea to the north and Canada’s Yukon province to the east – is a section of the refuge called the coastal plain, or section 1002.

On one side of the debate: Alaska’s Republican lawmakers, its Native corporations and a fossil fuel industry that sees the estimated 7.7 billion barrels of oil under the coastal plain a boon to the state’s flagging economy that has suffered from low oil prices on the global market and a decline in crude flowing through the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

On the other side: Environmental groups and the indigenous Gwich'in people, who consider the coastal plain sacred land and say oil drilling would ruin a fragile habitat for gray wolves, polar bears, porcupine caribou and more than 200 species of migratory birds.

“ANWR is a national treasure and an amazing piece of land,” Nicole Whittington-Evans, the Wilderness Society’s Alaska regional director, told Fox News. “It is not a place where oil and gas development should be allowed.”

The refuge was created in 1980 as part of comprehensive public-lands legislation signed into law by President Jimmy Carter that put more than 100 million federal acres in Alaska under conservation protection. Lawmakers at the time recognized the potential for oil drilling on the coastal plain, but they prohibited leasing or other development on the land unless authorized by a future Congress.

ANWR Facts

- Refuge was created in 1980 under Carter Adminstration

- Encompasses 19 million acres along Alaska's northesatern border with Canada

- Home to polar bears, porcupine caribou, gray wolves and over 200 species of migratory birds

- There are an estimated 7.7 billion barrels of oil under ANWR's coastal plain

That is basically where the issue has stood for the past 37 years as Alaskan lawmakers’ and oil industry executives’ advances have been thwarted in Congress.

In 1995, the Alaskan delegation inserted a provision opening ANWR to development in a budget reconciliation bill, but the bill was vetoed by President Bill Clinton. In 2005, despite having the Senate, House and White House all in Republican hands, a push to open ANWR was also unsuccessful as a number of moderate Republicans voted against it

But with a more polarized Congress in 2017 – and little willingness from either party to cross the aisle – both supporters and opponents of drilling in ANWR see drilling as a very real possibility.

One option available to Alaskan lawmakers – and a scenario that increasingly concerns environmental groups – is repeating their move in 1995 and attaching an ANWR provision to a budget reconciliation bill. This only requires 51 votes, cannot be filibustered and, unlike in 1995, won’t face the threat of a veto by a Democratic president.

“Republicans may try to put drilling in the Arctic into the budget reconciliation bill,” Athan Manuel, the director of the land protection program at the Sierra Club, told Fox News. “So we have our work cut out for us to win over some Republicans.”

Whether or not ANWR makes it into a budget reconciliation bill anytime soon is still unclear, but what is clear are the divisions between the Alaska Native Corporations that have boiled up to the surface in light of the prospect of drilling in the region.

Arctic Slope Regional Corp. has already pulled out of the Inuit Arctic Business Alliance – a group that, along with Bering Straits Native Corp., it helped found in 2015 to ensure that each corporation benefited from development in the Arctic.

Rock said that his company’s departure from the group had nothing to do with the conflict over ANWR, but the move came three weeks after his sharply worded letter in which he called Schubert’s lobbying to Congress “a breach of terms and obligations.”

"I therefore request that you cease these efforts immediately and desist from any further efforts that would result in an infringement of ASRC's property rights," Rock wrote. "Otherwise, ASRC will take any and all legal remedies available to rectify the situation."