Fox News Flash top headlines for January 26

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

- The Minnesota Legislature initiated debate on whether the state should permit physician-assisted suicide.

- A House health committee held a hearing ahead of the legislative session.

- Democratic Rep. Mike Freiberg, the lead sponsor, cited positive experiences in states like Oregon and Washington with similar laws.

The Minnesota Legislature kicked off debate Thursday on whether the state should join the list of those that allow physician-assisted suicide.

A House health committee took the unusual step of giving the bill a hearing even before the legislative session formally convenes Feb. 12. The lead sponsor, Democratic Rep. Mike Freiberg, of Golden Valley, who first introduced a similar proposal in 2015, said at a news conference beforehand that he was confident it will pass at least the House this year. Years of experience in states with similar laws such as Oregon and Washington, show that they work as intended, and they are used only by a narrow group of patients with terminal illnesses, he said.

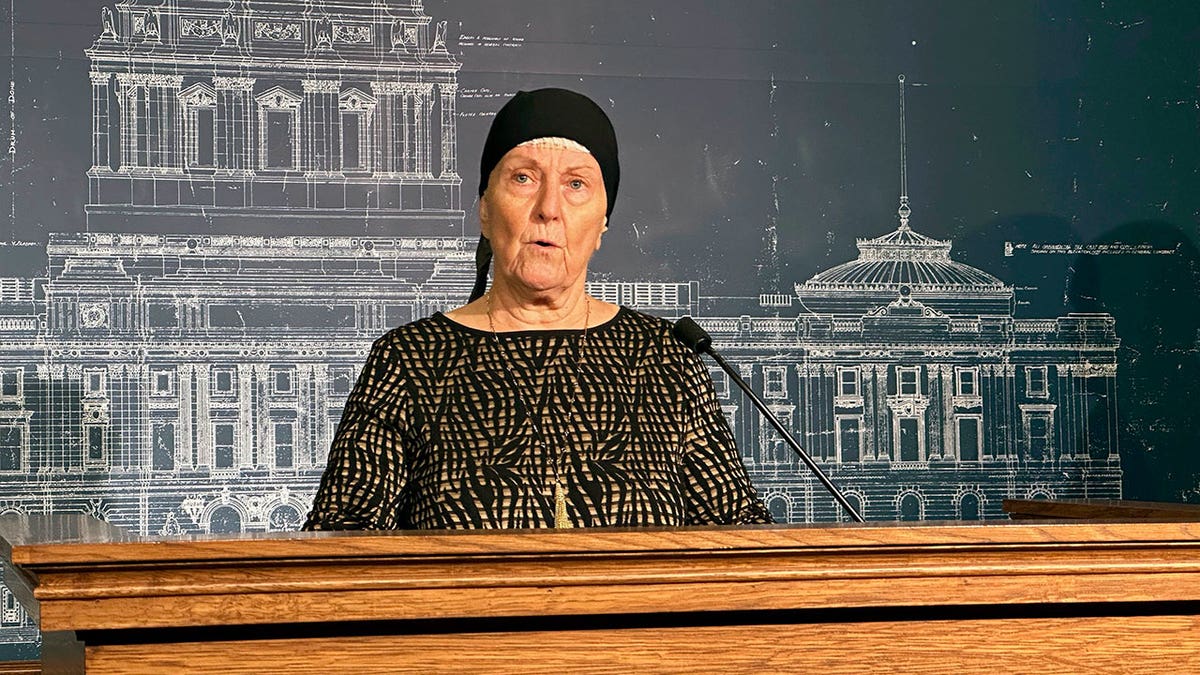

Nancy Unde, of Corcoran, who was diagnosed with an aggressive form of brain cancer in late 2022, told reporters that she wants the right to choose a peaceful, painless death on her own terms.

"This bill has been in front of the Minnesota legislature for 10 years already. It’s time to act," Unde said. "As I imagine the end of my life, I would like to be able to say my goodbyes and go peacefully. I’m thankful that we have hospice as an option. I will use it for the maximum comfort I can. But if it’s not enough, in the end, I want the option to die gently in my sleep."

Nancy Unde, of Corcoran, Minn., who was diagnosed with an aggressive form of brain cancer in late 2022, speaks on Jan. 25, 2024, at the State Capitol in St. Paul, Minn. Ten states and the District of Columbia already allow some form of physician-assisted suicide, while proponents are planning fresh pushes to pass it this year in several other states. (AP Photo/Steve Karnowski)

Ten states and the District of Columbia already allow some form of physician-assisted suicide, while proponents are planning fresh pushes to pass it this year in several other states. Oregon became the first state to legalize it in 1994. Vermont dropped its residency requirement last May, while Oregon did so in 2022.

While a New York bill has stalled for years, it is slowly gaining momentum with more lawmakers signing on as sponsors. Supporters in Connecticut held a news conference two weeks ago to announce a renewed effort after it passed one committee last year but stalled in another. A terminally ill Connecticut woman made news earlier this month by traveling to Vermont to end her life.

The Minnesota bill would allow patients age 18 and older who are suffering terminal illnesses and have less than six months to live obtain drugs they could take to end their own lives. The safeguards include a requirement that two providers, one of whom must be a physician, would have to certify that the patient meets the criteria. Patients would have to have the mental capacity to make their own health care decisions and provide informed consent, so those with dementia would not qualify. They would have to take the drugs themselves. The bill does not require that patients be Minnesota residents.

Freiberg said he is optimistic because his bill already has around 25 cosponsors, and that it's "consistent with legislation that advances bodily autonomy" — abortion and trans rights bills — that became law last year. But its prospects are less clear in the Senate, where Democrats hold just a one-seat majority and one Democratic senator, John Hoffman, of Champlin, has already come out against the proposal.

Freiberg said he was hopeful of getting some Republican support. But no GOP lawmakers on the committee were present at the start of the hearing, which drew an overflow crowd and a long list of testifiers, though they arrived later and offered amendments aimed at softening the impact of the bill.

ASSISTED DEATHS MAY SOON BE A REALITY FOR THOSE SUFFERING FROM MENTAL ILLNESS IN CANADA

"Intentionally ending a human life is wrong. It doesn’t matter what name we call it," testified Chris Massoglia, of Blaine, representing Americans United for Life. "Suicide is not health care. And it’s completely unnecessary due to the advances in palliative and end-of-life care."

Nancy Utoft, president of the Minnesota Alliance for Ethical Healthcare, said at a news conference beforehand that the legislation lacks sufficient safeguards to protect the elderly, disabled and other vulnerable people. Current law already gives people the right to make legally binding end-of-care health care directives, the right to hospice and palliative care, and the right to refuse care, she said.

"If these rights were better known and executed, we wouldn’t hear the heartbreaking stories of over-treatment often shared by assisted suicide proponents," Utoft said. "Let’s prioritize policies that promote better care for everyone."