US scientists release report on climate change

The federal report by dozens of U.S. government scientists concludes climate change is real and is driven almost exclusively by human activity.

Scientific studies used by the Obama administration to help justify tough environmental regulations are coming under intensifying scrutiny, with critics questioning their merit as the Trump EPA reverses or delays some of those rules.

In one case, agencies determined the research used to prop up a ban on a pesticide was questionable. On another front, the Environmental Protection Agency never complied with a congressional subpoena for the data used to justify most Obama administration air quality rules.

“EPA regulations are based on secret data developed in the 1990s,” Steve Milloy, who served on President Trump’s EPA transition team, told Fox News. “For the EPA, coming up with cherry-picked data is standard operating procedure.”

Milloy, author of “Scare Pollution: Why and How to Fix the EPA,” was previously a lawyer for the Securities and Exchange Commission and is among critics who accuse federal agencies of carefully selecting scientific research to fit a political agenda.

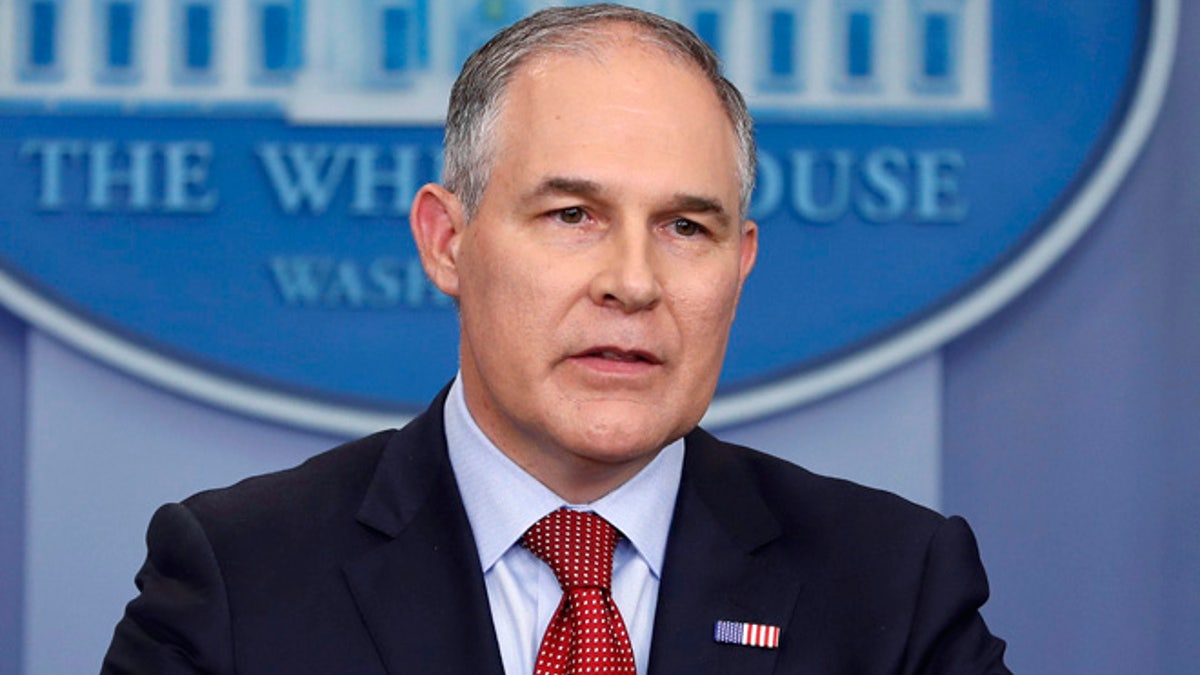

In October, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt issued a directive to ensure that individuals serving on EPA advisory committees don’t get EPA grants and are free from potential conflicts of interest.

“Whatever science comes out of EPA, shouldn’t be political science,” Pruitt said in a statement. “From this day forward, EPA advisory committee members will be financially independent from the agency.”

Environmental groups blasted the decision.

“For Pruitt, anything that helps corporate polluters make money is good and science and facts are just roadblocks he wants to tear down,” said Michael Brune, executive director of the Sierra Club.

Pruitt has become one of the most controversial members of the Trump administration in its first year, cast by his detractors as battling the kinds of regulations his agency is supposed to be upholding. But his office suggests many of those rules were flawed from the start.

Here’s a look at some of the most controversial studies behind those regulations:

Pesticide Ban

Pruitt recently reversed the 2015 ban on the insecticide chlorpyrifos for agricultural use, amid questions over the process.

The Obama administration’s EPA had originally justified the ban based on a study by the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health, which said the insecticide was linked to childhood developmental delays. While it was already banned for home use since 2000, the decision put the U.S. at odds with over 100 countries that allow the chemical for agricultural purposes.

Government agencies later questioned the findings.

EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt has been rolling back key Obama-era regulations. (AP)

The EPA Scientific Advisory Panel’s meeting report said: “[T]he majority of the Panel considers the Agency’s use of the results from a single longitudinal study to make a decision with immense ramifications based on the use of cord blood measures of chlorpyrifos as a PoD for risk assessment as premature and possibly inappropriate.”

The USDA stated it had “grave concerns about the EPA process...and severe doubts about the validity of the scientific conclusions underpinning EPA’s latest chlorpyrifos risk assessment.”

The center also gets EPA funding, noted Angela Logomasini, senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a free-market think tank.

“Agencies shouldn’t be able to cherry-pick. It’s a problem with administrative procedures across the board,” Logomasini told Fox News. “When money goes to politically active research groups, it’s government funding of the science.”

Harvard Study

The Obama administration’s EPA used the 1993 Harvard Six Cities Study to justify air quality regulations on particulate matter, or particles of pollution in the air. The regulations—linked to devastating the coal industry—also affect automobiles, power plants and factories.

In 2013 the House Science, Space and Technology Committee subpoenaed the EPA for data from the study, which links particulate air pollution to infant mortality.

'The American people should be confident that when agencies regulate, they rely on up-to-date, accurate, and unbiased information.'

But in 2014, then-EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy told the committee the agency couldn’t produce either the Harvard study or information from a 1994 American Cancer Society study—claiming the EPA didn’t own the information.

Congress tried to get information from then-EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy on the science behind the agency's air regulations. (AP)

“We did a very large analysis for California, which has arguably the most detailed database in the U.S. of mortality, and couldn't find any acute deaths due to PM2.5, even during the raging wildfires of 2007, when levels went through the roof,” Hank Campbell, president of the American Council on Science and Health, told Fox News.

For its part, Harvard argues regulations that stemmed from the report’s recommendations saved lives and were cost-effective.

Global Warming Hiatus?

The House science committee also is investigating the process behind a 2015 report from a team of scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, led by Thomas Karl, director of the agency’s National Climate Data Center.

Committee Chairman Lamar Smith, R-Texas., said the timing of the global warming report was curious because it lined up with the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan and the Paris Climate Conference (both of which the Trump administration now plans to abandon).

Karl denied the paper was released for political reasons, but critics linked it to a period between 1998 and 2013 known as the climate change “hiatus” -- when the rate of global temperature growth slowed.

John Bates, former principal scientist at the National Climatic Data Center in Asheville, N.C., said the study was issued with the purpose of discrediting any hiatus. Another scientist, Judith Curry, formerly of Georgia Tech, asserted that NOAA, a division of the Commerce Department, excluded certain data from their study in order to reach their preferred conclusion.

Commerce Department spokesman James Rockas said the matter is under review. In response to lawmakers’ concerns, “and in the interest of assuring the highest scientific standards, Commerce engaged outside experts to evaluate Department processes with regard to the production of scientific studies,” Rockas told Fox News.

Formaldehyde Findings

Under Pruitt, the EPA also moved the compliance date back for a 2010 rule setting emission standards for formaldehyde in composite wood products. Formaldehyde is a potential carcinogen.

The regulation was driven by the EPA’s office of Integrated Risk Information System, or IRIS, which produces chemical risk assessments to identify potential health hazards that other agency programs use to set standards.

“IRIS studies raised a whole host of questions with the formaldehyde regulation,” CEI’s Logomasini said.

The National Research Council—part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine—urged the EPA to reform IRIS and, in 2011, found the IRIS conclusions on formaldehyde had “[p]roblems with clarity and transparency of the methods” that “appear to be a repeating theme over the years.”

Pre-Diabetes ‘Epidemic’

Last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched a website, “DoIHavePreDiabetes.org.”

The CDC designated 5.7 percent for the average blood sugar level, or A1C, as being a “pre-diabetic” condition. This would mean 85 million Americans are pre-diabetic, said Campbell, of the American Council on Science and Health.

“Basically, CDC created an arbitrary standard that the rest of the world refuses to recognize as valid,” Campbell said. “The government hoped to scare people into changing their diets.”

Campbell pointed to National Institutes of Health numbers that only about 5 percent to 10 percent of people with that blood sugar level will develop diabetes. The World Health Organization and the International Diabetes Federation effectively stopped talking about prediabetes in 2014.

Health leaders around the world are working to address both prediabetes and diabetes, said CDC spokeswoman Alaina Robertson.

“The prediabetes category is very diverse and includes varying levels of elevated blood glucose,” Robertson told Fox News in an email. “This includes those with fewer risk factors and lower blood glucose (those closest to 5 percent); and those with significant risk factors and more elevated glucose levels (those closer to, and in some cases exceeding, 10 percent).”

Vaping Danger

Because the nicotine in e-cigarettes is derived from tobacco, the Food and Drug Administration can regulate it and the CDC issues warnings. Campbell and others stress research overwhelmingly shows that vaping helps smoking cessation and poses nowhere near the same risk as smoking.

The CDC’s own 2015 National Health Interview Survey found a majority of former smokers, 63 percent in 2014 and 66 percent in 2015, vaped every day. But Campbell said the agency tends to de-emphasize cessation and focus on e-cigarette addiction.

“The CDC's use of surveys to undermine the harm reduction and smoking cessation viability of e-cigarettes is junk science,” Campbell said.

However, there is good reason for caution, CDC spokesman Joel London told Fox News.

“The bottom line is that e-cigarettes have the potential to benefit adult smokers who are not pregnant if used as a complete substitute for regular cigarettes and other smoked tobacco products,” London said. “At present, the scientific evidence is insufficient to recommend e-cigarettes for smoking cessation, and e-cigarettes are not currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a quit smoking aid.”

Congressional Action

Some members of Congress back legislation to require agencies to rely on the “best available science” and consider a body of research, rather than a single study backing up a pre-existing decision. The bill also requires agencies to make the data available to Congress and the public.

The Better Evaluation of Science and Technology Act, or “BEST Act,” is sponsored in the House by Republican Reps. Ralph Norman of South Carolina and Paul Gosar of Arizona and in the Senate by Sen. James Lankford, R-Okla.

A coalition of 10 conservative organizations signed a letter to Congress backing the bill.

“The American people should be confident that when agencies regulate, they rely on up-to-date, accurate, and unbiased information,” Lankford told Fox News.

However, such oversight could “cripple the ability of agencies … to rely on scientific evidence to issue public health and safety safeguards,” Yogin Kothari, Washington representative for the Center for Science and Democracy, said in a statement earlier this year.

“Likewise, the tobacco industry would have been able to cast doubt on the link between cigarettes and lung cancer,” Kothari wrote. “The list goes on. Today, you can imagine the fossil fuel industry using the vague language to attack climate science as a justification for slowing down solutions that prevent global warming.”