A series of rituals usually unfold on Capitol Hill when a candidate wins a special election and joins the House in the middle of a Congress.

At that moment, they’re just a face in the crowd. But soon they’ll be a member of Congress.

The rookies show up on Capitol Hill wide-eyed, not knowing their way to the restrooms let alone the path to the House floor. There’s usually a small reception for supporters and family members, featuring punch and finger foods in the bare-bones, stripped-down Capitol Hill office that belonged to their predecessor. Then the victor heads across the street from the House office buildings to the Capitol for a mock swearing-in with the speaker of the House.

Family members clamor around the congressman-elect for the photo-op. An official photographer snaps photos of the speaker posing with the family. The speaker usually jokes around and makes light conversation. The lawmaker-elect fumbles with the family Bible and inevitably raises the wrong hand before the speaker corrects them. Finally everyone stands up straight and smiles for the money shot.

A few local reporters sometimes fly in from the politician’s home state. They furiously scribble down “color” in their notebooks for their pieces about the lawmaker-elect’s day.

“P. Ryan taller in person” jotted down an out-of-town, female correspondent at one recent ceremony. Sometimes a camera crew or two shoots a few frames of video. The networks may show up. Maybe not. Then the speaker’s staff escorts the newbie to the House floor for the official swearing-in.

That’s where the real thing happens. The House is almost always in the middle of a vote series. The swearing-in comes between the first and second roll call tally. The speaker climbs to the dais to preside. Bipartisan members from the congressman-elect’s state squeeze into the well of the chamber. Sometimes the state’s senators walk across the Capitol to observe.

The most-senior member of the delegation usually makes a few glowing remarks about the latest addition to the House. The speaker then asks the member-elect to present himself or herself in the well and raise their right hand. The speaker administers the oath of office. Everyone cheers. The speaker then asks the now congressman or congresswoman to deliver a short speech.

The most-junior member of the House thanks a lot of people. They hope they can work with members from both sides of the aisle to get things done. They discuss what an honor it is to become a House member.

They acknowledge their family members sitting in the gallery above the floor. Then it’s over. The speaker announces the updated membership of the House and the body returns to voting. Someone has to instruct the new representative how to use the voting machine because, well, they’re now a member of Congress and voting is kind of important around here.

This ritual plays out multiple times each Congress following a special election victory. Some newly-minted lawmakers arrive on Capitol Hill with “celebrity” status. That may command a few more reporters and cameras if someone emerges victorious from a high-pitched special election. Their win could represent a political bellwether or forecast a trend for the next election.

The formalities to swear-in Rep. Warren Davidson, R-Ohio, received sizable attention in June of last year. Davidson won a special election to take the Ohio House seat vacated by former GOP House Speaker John Boehner.

Not as many reporters and cameras materialized in November of last year to swear-in Reps. James Comer, R-N.Y., Dwight Evans, D-Pa., and Colleen Hanabusa, D-Hawaii.

That trio was elected to fill out terms of members who either resigned due to scandal or died. Comer and Evans were brand-new to the Capitol. Hanabusa returned to the House after an unsuccessful Senate bid.

But these customs usually don’t garner much attention amid the daily political maelstroms that consume Capitol Hill. The new members usually fade into congressional oblivion unless they’re a known figure. A case in point was the 2013 return to elected office by Rep. Mark Sanford, R-S.C.

The South Carolina legislature censured Sanford after lying about his affair and covert trip to Argentina to visit his paramour, Maria Belen Chapur while he was governor. Sanford then succeeded now-Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., in the House -- a position he held previously for six years.

There was a little bit of press for the ersatz swearing-in of Rep. Ron Estes, R-Kansas, this spring to succeed CIA Director and former Rep. Mike Pompeo, R-Kansas. That’s because Democrats made the right-leaning district somewhat competitive in hopes of stealing the seat.

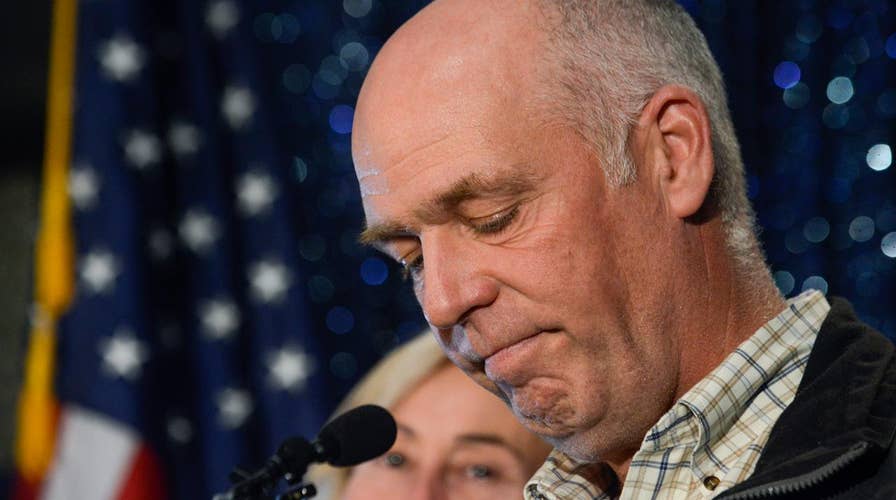

But brace yourself for what will unfold when Rep.-elect Greg Gianforte, R-Mont., arrives on Capitol Hill to be sworn-in come early June.

The speaker’s office hasn’t yet set the date to swear-in Gianforte. It’s likely to be June 6 or 7. But reporters may well be staking out suite 1419 Longworth vacated by Interior Secretary and former Rep. Ryan Zinke, R-Mont., now just to holler a few questions at Gianforte.

One can only imagine how many cameras will cram into the speaker’s ceremonial office for the mock swearing-in, to say nothing of those rubbering into the press gallery for the real thing.

How will lawmakers interact with Gianforte? Will Republicans shun him? How jocular will House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis., be with Gianforte compared to other special election winners? What will Gianforte say to the House? Will a din of applause and cheering swell in the House chamber once Gianforte takes the oath?

Will Montana’s two senators, Sens. Jon Tester, a Democrat, and Steve Daines, Republican, appear for the ceremony? The absence of either or both would be noticeable.

Montana sends but a three-person delegation to Washington, and Gianforte will be the only House member. How does Gianforte comport himself after he’s here? Does he deliberately fade from the public view? It’s hard to become a member of the “Invisible Caucus” on Capitol Hill when you’ve done something as visible as Gianforte.

Gianforte is expected in court sometime in the next few days after the Gallatin County, Montana Sheriff’s Department issued a misdemeanor citation for body-slamming reporter Ben Jacobs of The Guardian. Don’t think that Democrats -- who are trying to put the House into play in 2018 -- won’t notice with whom Gianforte associates.

“He's going to learn very quickly that once you’re a member, it is a lot harder to run away from your party or a tough vote,” said a senior House Democratic aide.

How will Gianforte’s relations with the press play out? In 2014, then-Rep. Michael Grimm, R-N.Y., threatened to throw a New York TV reporter off a ledge in the Cannon House Office Building. “I’ll break you in half … like a boy,” boasted Grimm. Grimm later resigned and did time, convicted of corruption charges.

Gianforte never issued a threat. He just upended Jacobs.

Ryan declared he wouldn’t stand in the way of seating Gianforte.

“I’m going to let them decide who they want,” he said. “It’s not our choice.”

But it is.

Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution grants both the House and Senate the right to “be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members.”

There hasn’t been a big brouhaha over seating a House member since 1984-85. Democrats ignored the Indiana election certification of Republican Rick McIntyre over Rep. Frank McCloskey, D-Ind., in 1984.

Democrats refused to seat either candidate until a bipartisan task force investigated the matter. Months later, the Democrat-controlled House decided McCloskey won the race by four votes. GOPers cried foul. The House voted along party lines to seat McCloskey.

There’s no active effort to oppose seating Gianforte.

The House’s Code of Conduct requires lawmakers to “behave at all times in a manner that shall reflect creditably on the House.”

Moreover, the bylaws of the House Ethics Committee allows that panel “to undertake an inquiry or investigation” to probe a member’s conduct. The incident with Jacobs unfolded prior to Gianforte’s membership in the House.

House rules and precedents limit the scope of a possible investigation to only when someone is a member. The House has rules about barring members from sitting on committees or voting if they’ve been convicted of a felony. So far, Gianforte hasn’t been convicted of anything and the charge is just a misdemeanor.

It’s possible the quasi-governmental Office of Congressional Ethics (OCE) could receive a complaint from a member of the public to probe Gianforte. But the OCE may encounter the same problems as the formal Ethics Committee since Gianforte’s alleged transgression happened prior to his Congressional service.

Freshmen House members always face the challenge of standing out from their colleagues. It’s even tougher for special election winners. It’s hard enough to distinguish yourself from a pack of 434 other people. Gianforte won’t suffer from that problem. And he’ll be a lot more than just a face in the crowd.