‘Extremely unlikely’ new SCOTUS justice could be confirmed before election: Expert

WSJ Supreme Court correspondent Jess Bravin on the possible election outcomes that could impact the future of the Supreme Court.

The confirmation of the next Supreme Court justice will hinge on two things: timing and math.

How fast can President Trump settle on a nominee? How fast can the administration vet that individual? How fast can the Senate consider the nominee and provide Constitutionally-mandated “advice and consent?” Finally, would a nominee have enough votes?

For starters, everything is on the cusp – ranging from the timing of a confirmation hearing to the roll call vote itself.

TRUMP SAYS SUPREME COURT PICK WILL ‘MOST LIKELY’ BE A WOMAN

It is extraordinary to have a Supreme Court vacancy this close to an election. And, past is prologue. Supreme Court nomination battles are always intense. But the melee over the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh exacerbated an already malignant situation. Kavanaugh’s confirmation brawl, augmented by allegations leveled by Christine Blasey Ford, propelled Capitol Hill into a political morass not seen since the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas in 1991. And before that, the failed confirmation vote on the floor of Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork in 1987.

You get the idea.

To wit:

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia passed away suddenly in February, 2016. It was an election year.

The Senate was in recess that week.

But within hours, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., made a unilateral decision: The Senate wouldn’t consider a nominee from President Obama. That decision should be left up to the new President in early 2017.

Mr. Obama eventually tapped District of Columbia Circuit Court Judge Merrick Garland to succeed Scalia. But despite Democratic exhortations for months, the Senate, under Republican control, never granted Garland a hearing.

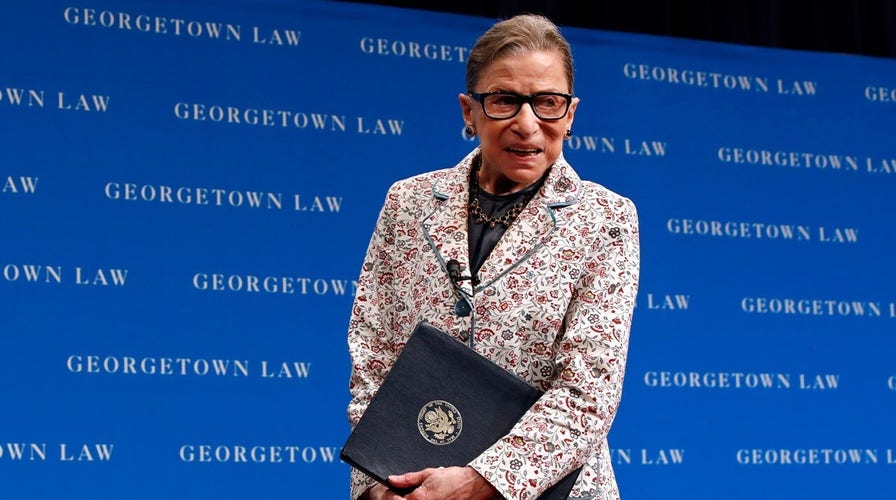

SUPREME COURT JUSTICES SHARE THOUGHTS OF LOSS AND PRAISE AFTER RBG DEATH

In the process, Garland emerged as a cause celebre of the left. An icon of what Democrats viewed was wrong with Republicans, and, specifically, the Majority Leader. Democrats felt McConnell’s gambit cheated their side out of a rightful seat on the Supreme Court. In turn, McConnell invoked something he dubbed “the Biden Rule.” McConnell’s contrivance certainly isn’t any sort of procedural regulation or part of the Standing Rules of the Senate. McConnell simply appropriated something Joe Biden said three decades ago about opposing filling vacant Supreme Court seats in an election year. McConnell made it sound like Biden’s musing was embossed on a stone tablet from Sinai.

But there is a caveat to McConnell’s 2016 resistance to confirm Garland. It was an election year. But McConnell notes Garland was the nominee of a Democratic President to a GOP-controlled Senate. The supposition today is that the Senate is in Republican hands during a Republican presidency. So, McConnell’s reasoning is that the Senate should fill the seat – soon.

This is where we enter the time and math equation.

In modern history, most Supreme Court nominees require 40-45 days from when the President submits their name to the Senate until they receive a confirmation hearing. Granted, the Trump Administration has already pre-vetted a number of prospective nominees. But this phase takes things to another level. Moreover, senators of both parties demand meetings with the nominee. Confirmation of a justice to the nation’s highest court is one of most hallowed responsibilities afforded a U.S senator. They take this responsibility very seriously. And don’t forget, Supreme Court nominations sometimes spill off the tracks.

The Senate ultimately confirmed Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh. But not after revolting, political fracases. President George W. Bush nominated White House Counsel Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court in 2005. But Miers ultimately withdrew within a month. Senators from both parties were surprised at the lack of depth in some of Miers’s answers to questions and “insulting” responses on her judicial questionnaire.

The Senate rejected Bork’s nomination on the floor, 58-42. Bork’s surname became a “verb.” The idea of “Borking” a nominee emerged as a parliamentary pastime on Capitol Hill.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

President Ronald Reagan then tapped Douglas Ginsburg as his Supreme Court pick. But that nomination collapsed as well. Ginsburg withdrew days later after it was reveled he smoked pot as a professor. Reagan finally settled on Justice Anthony Kennedy.

So, anything can happen once the president picks a nominee. Supreme Court nominations can self-destruct over weird things. And even when they don’t, political dramas can erupt. Such were the cases with Thomas and Kavanaugh.

McConnell could face resistance from some GOPers who want to be more deliberative about the pacing of a nomination. The average period from the nomination to floor confirmation for a Supreme Court Justice is 67-71 days. So that could mean a vote in late November or early December.

And, what will happen if we know in late November or December that President Trump is a lame duck? Or, that the Senate is switching control in January? Or both?

This ultimately boils down to whether a nominee scores the votes for confirmation on the floor. It’s always about the math on Capitol Hill.

The Senate breakdown is thus: 53 Republicans and 47 senators who caucus with the Democrats. Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, doesn’t want to move a nominee now. She faces a competitive re-election bid this fall. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, isn’t on the ballot in November. But, Murkowski also indicated the Senate should refrain from considering Supreme Court nominees until after the inauguration. Murkowski was the lone GOP senator to “technically” oppose Kavanaugh in 2018. As it turned out, Murkowski voted “present” to offset what would have been a “yea” vote by Sen. Steve Daines, R-Mont. Daines was absent that day two falls ago to attend the wedding of his daughter in Montana. Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, could also be in play. Romney cast the lone GOP ballot to convict President Trump on one article of impeachment.

Senators don’t like to be told what to do, be it by Mr. Trump or McConnell.

GOPers can lose two votes and still confirm a nominee. They can lose three votes and have Vice President Mike Pence break the tie. Never before has a vice president broken a tie to confirm a Supreme Court nominee. In fact, no vice president had ever broken a tie to confirm any executive branch appointment until Pence.

In 2017, Pence broke a tie to confirm Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. In 2018, Pence broke a tie to confirm former Sen. Sam Brownback, R-Kan.,as Ambassador for International Religious Freedom. A few days later, Pence broke a third tie to confirm Russ Vought as Budget Director.

All of this is set against the backdrop of a pandemic. In fact, Supreme Court nomination fights have grown so hyperkinetic, this could well overtake coronavirus as one of the defining issues of the fall.

Timing and math are key to this entire process.

And one more ingredient: unprecedented toxicity in the Senate hallways.