One of the questions facing Americans these days is whether we live in a culture of honor or a culture of victimization. Though these two cultures share the same land and history, they could not differ more vastly in how one lives life.

To live in the culture of honor, the emphasis is always on self-mastery: make something of yourself. This culture believes the more the individual develops oneself, the stronger of an asset the individual is to society. It is often these men and women who lead productive lives, contribute wisely, and even make history.

On the other hand, to live within the culture of victimization, the individual lives in a world largely defined by horrific deeds that took place in the past. This form of existence derives its power not from individual agency but by invoking the specter of past horrors. Within this culture, the emphasis is often placed on loyalty to the group over the individual.

When I arrived in Atlanta in the middle of the ongoing voter-bill controversy, I felt a strong connection to the culture of honor that built and shaped this city. As I drove on the tree-lined freeways and streets, I saw endless tributes to civil rights leaders, including Ralph Abernathy and Martin Luther King, Jr. Seventy years ago in segregated Atlanta, these honors would have been unimaginable.

But these men and women had refused to accept the fate of inferiority assigned to them by Whites and the local, state, and federal governments. Instead, these self-made individuals lived within the culture of honor and it was their display of unimpeachable morality that forced many racists into a reckoning with their un-American hypocrisies. These resilient people changed America.

As I thought of them, I felt a strange sense of disconnect. I came to Atlanta because the new voting bill signed by Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp had been called "Jim Crow 2.0." One could argue that the timing of the bill was questionable, coming on the heels of one of America’s oddest elections. Nearly all of the fraud charges had been dismissed and it was easy to see why many Georgians would be skeptical of the need to change voting rules. But were these rules worthy of the Jim Crow 2.0 label?

President Biden meets with members of the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus Executive Committee in the Oval Office at the White House on April 15, 2021 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Doug Mills-Pool/Getty Images)

Growing up in a civil rights family, I was fairly young when I learned about voter suppression during the Jim Crow era.

To this day, I have never passed the literacy tests that often required Blacks to answer 30 questions correctly and under 10 minutes in order to vote. Here are two questions: "Write every other word in the first line and print every third word in the same line, but capitalize the fifth word that you write" and "Divide a vertical line into two equal parts by bisecting it with a curve horizontal line that is straight at the point of bisection of the vertical." Imagine how many Americans today would be disenfranchised if they had to pass such a test.

And this was not even the worst form of voter suppression by far. On Election Day in 1920, two wealthy Black landowners, July Perry and Mose Norman, tried to vote along with other Black people in the small central Florida town of Ocoee. By the next morning, Perry was lynched, Norman disappeared, and all 500 Blacks, except for one, were ran out of Ocoee, which remained virtually all-White until the 1980s.

Perhaps that is why my strange feeling of disconnect only intensified as I listened to President Biden denounce the water restrictions, an act so pernicious that it warranted a name bigger than Jim Crow: "Jim Eagle." I read through the bill and did not see the horrors of the past sneaking into the present. People may hand out water as long as they are 150 feet away from the polls. There will be two Sundays for "souls to the polls" voting.

To eliminate the five-hour waits to vote, the bill mandates more voting equipment and access. As for the controversial voter ID requirements, the long list of acceptable IDs includes utility bills. There were certainly some questionable items in the bill, including the removal of the secretary of state from the elections board, but nothing that resembled Jim Crow or Jim Eagle.

GOP STATE LEGISLATURES MOVE AHEAD WITH ELECTION SECURITY BILLS AMID OUTRAGE OVER GEORGIA LAW

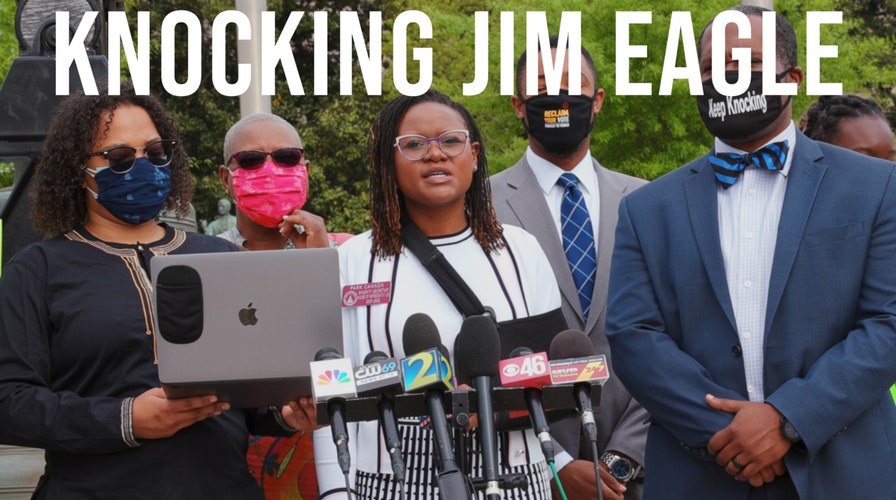

I then learned that Georgia State Rep. Park Cannon was giving a news conference in Liberty Park across the street from the state Capitol. Cannon had been arrested two weeks prior for refusing to stop knocking on Kemp’s door as he signed the voting bill.

I wanted to hear from Cannon what exactly was Jim Crow 2.0 about the new bill. Instead, Cannon spent the next 10 minutes describing her arrest and the bill with provocative terms: "nooses around our necks," "lynchings," "apartheid," "good ole boys," "racists," and on. (See the accompanying video to hear Cannon in her own words.)

It was not until several hours later that I realized that Cannon was speaking to us from within the culture of victimization. If this bill was indeed Jim Crow 2.0, then would it not be prudent to point to the exact specifics so that the citizens of Georgia may lead a recall effort against Gov. Kemp? Instead, the use of the past Jim Crow horrors by Cannon and her counterparts, including Stacey Abrams, had the intended effect of casting a dark cloud over the state, raining down confusion.

Workers load an All-Star sign onto a trailer after it was removed from Truist Park in Atlanta, Tuesday, April 6, 2021. (John Spink/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP) (AP)

The allure of the culture of victimization lies in its ability to grant power to those willing to cast the other side as oppressors by donning the cloak of victimhood. It matters none that Cannon, born in 1991, never suffered the evils of Jim Crow directly. She knows that if anyone questions her all she has to do is levy the charge of racism in return and that is a tremendous power to possess in today's America.

But this power is a limited one. By choosing to live within the culture of victimization, Cannon will always be beholden to this power — why give up this power when the culture of honor promises nothing in return?

The most unfortunate result of this racial confusion was the decision by Major League Baseball to move the All-Star game from majority-Black Atlanta to mostly White Denver. Many have estimated this loss to be in the millions of dollars. As I spoke with Atlantans, such as Shelley Wynter of WSB radio and Marvil Rodney of Rodney's Jamaican Soul Food, it became clear that the wage-earners would be mostly affected. Wynter pointed out that many locals saw the All-Star Game as a way to overcome losses from the pandemic. Rodney said in addition to that he would have to do things like cancel a $20,000 order for meat that he had planned for that week of festivities. Both men were self-made men who were looking forward to hosting Americans from all over in the city shaped by legends like Ralph Abernathy and Martin Luther King.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

In other words, the folks who lived within the culture of honor would have to pay for the follies of those who live within the culture of victimization, as well as those who fear the power of these people. It speaks volumes to where we are as a country.

Eli Steele is a documentary filmmaker and writer. His latest film is "What Killed Michael Brown?" Twitter: @Hebro_Steele