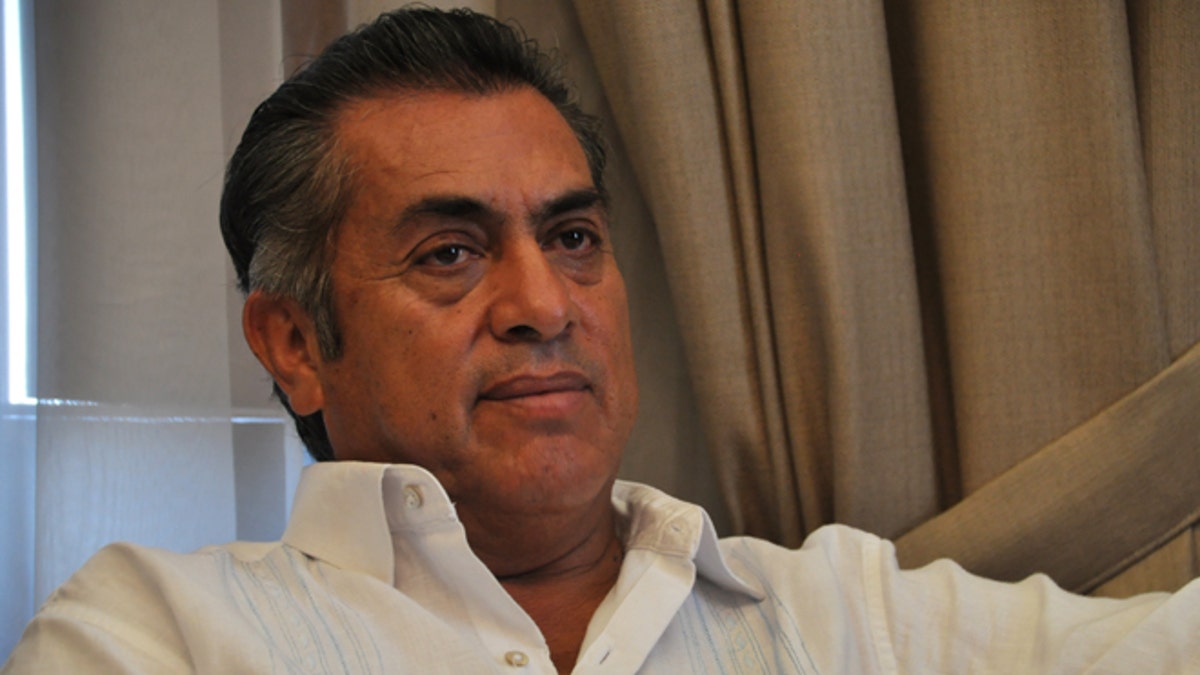

Mexican Gov. Jaime Rodriguez Calderon, aka "El Bronco." (Jan-Albert Hootsen/Fox News Latino)

MONTERREY, Mexico – A year after Jaime Rodríguez Calderón, an independent, rose to power as governor of Mexico’s wealthiest state, he still radiates the confidence that helped sweep him into office in a wave of populist anger.

Rodriguez, Nuevo León’s top official since October 2015, is the proud standard bearer for those dismayed by the country’s three leading political parties.

“Ask me whatever you want to ask,” he said, smiling. “And I will answer as I please.”

A former mayor, Rodríguez is widely known by his nickname “El Bronco,” a reference to his somewhat unwieldy temperament. He ran on a non-partisan platform, supported by Monterrey’s powerful business community and vowing to bring down the traditional political parties, which are considered by many in Mexico to be the most corrupt and least accountable institutions.

“I don’t owe anything to vested interests or political parties, only to civil society,” Rodríguez told Fox News Latino. “People are sick and tired of the old system.”

The governor recently announced that he will run for the presidency in 2018.

Showing FNL some stats of his social media presence, he said he believes he can be competitive in the elections against more traditional candidates like PRD leader Andrés Manuel López Obrador and conservative Margarita Zavala, the wife of former PANista president, Felipe Calderón.

“The social network is my favorite tool. It allows me to be everywhere without actually being anywhere,” he said.

“I believe we can organize a campaign without much money,” he added. “López Obrador is traveling through the country and Zavala is organizing a traditional campaign, using Mexicans’ money. That’s perverse.”

Whether he actually stands a chance in 2018 is an open question.

According to Mauricio Sada, a one-time member of PAN who now supports independent candidates, El Bronco is overestimating the success he had in Nuevo León.

“He’s trying to extrapolate that to a national level, but I think it’ll be very difficult for him," Sada said.

Once a rancher and a horse breeder who grew up poor, Rodriguez was in the Party of the Institutional Revolution, or PRI, for more than 30 years before going independent.

It’s clear that Rodríguez, 58, would never have gone rogue and broken with the PRI had the party not snubbed him as a gubernatorial candidate.

Before winning the governorship, he was at least as famous for having survived two assassination attempts when he was mayor of the city of García and for suffering through the kidnapping and murder of one of his sons, as for any policies he pursued.

Once at the helm of Nuevo León, Rodríguez became the most high profile elected official among the first batch of independent candidates who took advantage of Mexico’s recently revised electoral laws, which allowed individuals not bound to the traditional party system to run for office.

Besides Rodríguez, two notable independents won office last year: Manuel Clouthier gained a seat in the federal chamber of deputies, and Pedro Kumamoto was elected to the state legislature of Jalisco.

“I believe that part of what I wanted to achieve, first as an independent candidate and now as an independent governor, is something that the political society wasn’t used to,” Rodríguez told FNL. “But society as a whole wanted change, and it happened here in Nuevo León.”

The appearance of independents on the Mexican political scene spurred enthusiasm and interest, but the politicians have little in common with each other apart from not being bound to any party.

“The independents aren’t actually a movement,” Jeffrey Weldon, a political scientist at Mexico City’s ITAM university, told FNL. “They got together a few times during the campaign on behalf of common interests, but they’re all very different people. They arose from a general discontent with the political parties.”

The entrenched political parties – the PRI, the ruling party of Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto, the leftist Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD), and the conservative National Action Party (PAN) – immediately responded to the independents as a serious threat. Since Rodríguez’s election, a number of states across Mexico, controlled by different parties, have passed laws requiring unaffiliated candidates to gather the signatures of 3 percent of registered voters to qualify and barring them from having been members of a political party for three years before running as independents.

Such laws are known in the press as “anti-Bronco laws.”

‘Something you can flaunt’

In large part, Rodríguez’s gubernatorial campaign was built on discontent over the disastrous administration of the outgoing governor, Rodrigo Medina, a member of PRI.

Medina left the state’s finances in shambles with historically high budget deficits, while violent crime spiked during his administration. Moreover, Medina and many of his closest associates have been accused of corruption and graft. Rodríguez’s main campaign promise, along with making Nuevo León safer and its government more accountable, was to put Medina behind bars and get back the money he says the former governor stole from the public coffers.

After a year in office, however, the governor, critics say, has done little to fulfill his promises. According to a recent poll, his approval rating has dropped below 50 percent.

Critics concede that Rodríguez has shored up Nuevo León’s finances, lowering the budget deficit while simultaneously creating a more transparent government.

In other areas, however, his government has accomplished little; violent crime remains a pervasive part of life, while promises like free public transportation haven’t materialized.

“He hasn’t achieved all that much. Balancing the budget is important, but it’s not something you can flaunt. On most other areas he has so far disappointed,” Mauricio Sada, a one-time member of PAN who now supports independent candidates, told FNL.

As for Rodríguez’s promise to put his predecessor behind bars, a judge recently dismissed fraud charges against Medina. A new trial on of abuse of power charges is now being prepared.

“We’re working on it,” Rodríguez told FNL. “It’s not something we want to rush.”

He went on, “We’re fighting to make this case go to court. Unfortunately, a governor cannot influence the judiciary, and the judiciary also suffers from the inertia of the past. But we are going to do this, I am not discouraged.”

The generally slow pace of change under his administration is no problem at all, he insists.

“I’ve said we would handle all these problems during my government, and my government has only been in power for one year,” he told FNL. “When you do things calmly, you do them better.”