Why impeachment talks are dangerous for Democrats

Panetta: Democrats should hold off on impeachment. How the impeachment debate will play out heading into midterm elections.

Democrats are increasingly whispering about the possibility of impeaching President Trump if they regain control of the House of Representatives in November, even as top Republicans openly suggest the move would backfire politically.

The wait-and-see approach to drafting articles of impeachment comes as voter pressure from the base rises. A late-August Washington Post-ABC poll found nearly 50 percent of Americans support immediate impeachment proceedings against the president. Four in 10 residents of Ohio, which Trump carried in the 2016 presidential election, said this week that the House should consider impeaching Trump, according to a Suffolk University poll.

But Democrats are mindful of alienating moderate and conservative voters in several key states they will need to win over in order to take the House and Senate, analysts say. (A PBS poll in April found that 47 percent of voters wouldn't back a congressional candidate who wanted Trump impeached, and Fox News polling indicates the GOP is pulling away in pivotal Senate contests even as Democrats make apparent gains in the House.)

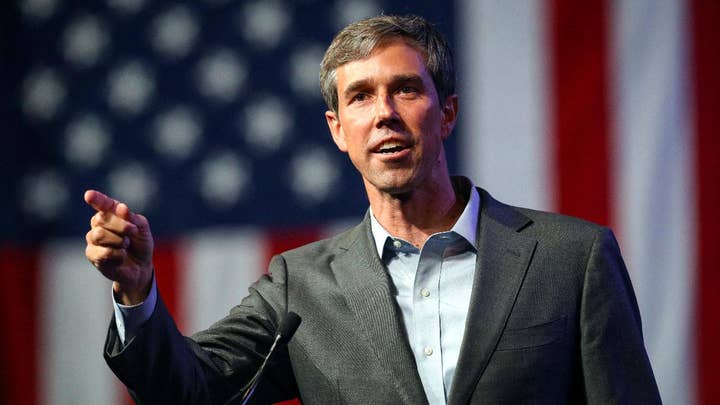

Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke, whose well-funded longshot bid to unseat GOP Sen. Ted Cruz has faltered in the polls in recent weeks, has emerged as one of the clearest examples of the Democrats' strategy.

“Impeachment, much like an indictment, shows that there is enough there for the case to proceed,” O’Rourke has said, “and at this point there is certainly enough there for the case to proceed.” However, the 46-year-old has clarified that although he would vote for impeaching Trump, he's also not in favor of actually initiating impeachment proceedings at the moment.

His even-handed approach on impeachment highlights the political tightrope Democrats must often walk in their effort to retake Congress this year. Even though no Democrat has won a statewide election in deep-red Texas in more than two decades, progressives poured a record-setting $38 million into O'Rourke's campaign last quarter because of his unique cross-party appeal.

Key Democrats have echoed O'Rourke's give-and-take stance. House Minority Whip Steny Hoyer, D-Md., called Trump's summer news conference with Russian President Vladimir Putin "treasonous," but said impeachment proceedings would be a "distraction." There would, he added, "be time for that" later.

"We need to get through this election; we need to deal with the economic issues; we need to deal with the health-care issues of the American people," he said.

During a Labor Day parade in Brooklyn, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., told a bystander who asked when Trump would be impeached, "The sooner the better. ... We gotta get a few Republicans. Democrats are on your side." A Schumer spokesperson later claimed the senator thought he was being asked when Democrats would "defeat" Trump.

Meanwhile, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., has said impeachment is "not a priority," at least until Special Counsel Robert Mueller announces the conclusions of his probe into the Trump administration's alleged dealings with Russia.

“Impeachment has to spring from something else,” Pelosi said. “If and when the information emerges about that, we’ll see. It’s not a priority on the agenda going forward unless something else comes forward.”

While O'Rourke, Schumer, and Pelosi have been noncommittal, other top Democrats and operatives have been more overt.

Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., said in a video posted last month that people have told her not to discuss impeachment yet. “And when they say that, I say ‘impeachment, impeachment, impeachment, impeachment, impeachment, impeachment, impeachment,'" Waters said in the video. She previously has advocated for her supporters to confront Trump's Cabinet members in public and "push back" on them.

A key obstacle for Democrats: As Trump himself has taken to pointing out, it's unclear what the basis for impeaching the president would be. And, while they determine how to proceed, Trump has shown no reluctance to hammer them as "low IQ" and "crazy" partisans.

"I don't even bring it up," Trump said at a recent rally in Montana. "Because I view it as something that, you know, they like to use the impeach word. Impeach Trump. Maxine Waters, 'We will impeach him.' But he didn't do anything wrong. 'It doesn't matter, we will impeach him. We will impeach.' But I say, how do you impeach somebody that's doing a great job that hasn't done anything wrong?"

The Constitution technically prescribes impeachment only for treason, bribery, and "high crimes and misdemeanors," a broad term of art that virtually all legal scholars agree encompasses more than just criminal offenses.

The framers knowingly appropriated the phrase from their English root. In the 17th and 18th centuries it had served as the basis for a variety of impeachments for behaviors by officeholders that, while objectionable, were not criminal. (India's governor general, Warren Hastings, was impeached in May 1787 -- the same month the Constitutional Convention convened in Philadelphia. Hastings was charged with criminal and non-criminal offenses, according to the Smithsonian Institution.)

WALMART PULLS 'IMPEACH 45' CLOTHING FROM WEBSITE AFTER MASSIVE BLOWBACK

However, constitutional attorney Ron Fein, who co-authored the book "The Constitution Demands It: The Case for the Impeachment of Donald Trump," has said it would be a mistake to believe former President Gerald Ford's claim that "[a]n impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history."

"Ford's [statement] may be a description of raw power, but it's not faithful to the Constitution," Fein, who also serves as legal director of Free Speech For People, told Fox News. (His book makes a nonpartisan case for impeaching Trump based on arguments by the founders, contemporaneous writings, legal precedents, and other sources.)

At the urging of delegates George Mason and James Madison, the scope of impeachable offenses was broadened at the Constitutional Convention from treason and bribery -- but only to a point.

While Madison wanted impeachment to encompass wrongs such as a president "betray[ing] his trust to foreign powers" and other misdeeds, he pointedly opposed permitting impeachment for presidents who committed the offense of "maladministration." So "vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during pleasure of the Senate," Madison argued.

And Charles Pinckney, one of the signers of the Constitution who served as a governor, representative and senator from South Carolina, warned that allowing Congress to impeach and remove a president would undermine the fundamental separation of powers between the three branches of government. Congress, Pinckney said, could wield the impeachment authority "as a rod over the Executive and by that means effectually destroy his independence."

There is, then, evidence the Constitution's framers did not endorse a limitless impeachment power because they worried about the effects such a process would have on the separation of powers -- although political partisanship may not have been on their minds.

GOP ENTHUSIASM INCREASES ACROSS THE BOARD IN WAKE OF KAVANAUGH SLUGFEST

"The founders didn't really talk about impeachment being a partisan issue, because they didn't anticipate political parties as we have them now. ... The concern that they talked about in the debates were the branches of government," Fein told Fox News.

Fein added that there are several viable grounds for Trump's impeachment. He said that Trump's "businesses all over the world that are receiving favors from foreign governments," for instance, could be an impeachable violation of the Constitution's Emoluments Clause.

That clause, which has never been interpreted definitively by the courts, ostensibly prevents Trump from "accept[ing] ... any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State."

"We have a sitting president who will undoubtedly be impeached."

In July, a federal judge allowed a lawsuit against the Trump administration on Emoluments Clause grounds to proceed. The ruling was the first time a federal court ever attempted to define "emolument," which is not defined in the Constitution.

"Plaintiffs have plausibly alleged that the President has been receiving or is potentially able to receive 'emoluments' from foreign, the federal and state governments in violation of the Constitution," the D.C. district court judge, Peter Messitte, wrote in his denial of the Justice Department's motion to dismiss the case.

However, Fein said, it's not necessary for Congress to wait on courts to decide the issue.

"Impeachment is entrusted to Congress," Fein told Fox News, adding that the Emoluments Clause is, by its own terms, in the domain of Congress. "That's not to say the court case can't have value."

Fein and others have cited additional potential grounds for impeachment. Some analysts, for example, have cited potential obstruction of justice, though some legal experts have questioned how Trump could be said to have obstructed justice by performing constitutionally permissible actions such as firing FBI Director James Comey.

“The cover-up is always worse than the crime, and this one is very shady,” said Andrew Hall, who represented a top adviser to then-President Richard Nixon during Watergate. "We have a sitting president who will undoubtedly be impeached."

Even assuming Democrats obtain the majority in the House of Representatives needed to secure impeachment, though, analysts have warned it would be virtually impossible to secure the two-thirds vote necessary in the Senate to remove the president from office. But some nevertheless suggested it shouldn't be an obstacle to pressing onward.

"If you look at Nixon, and tried to count noses in terms of who was in favor of impeachment at the beginning, it would have been close to zero," Fein said. "And if you looked at public support for impeaching Nixon, it was in the 30s, and didn't rise up to 50 percent until the House Judiciary Committee went ahead and approved articles of impeachment.

"We could see the same thing with Trump," he added, noting that some scholars also have seen the impeachment process as a useful way to generate new legal norms. "Impeachment hearings could be a national education process that the country would watch and experience and learn."

The country has seen the process fully play out only twice. President Andrew Johnson's impeachment in 1868, for allegedly violating what experts have concluded was an unconstitutional law, was unpopular but ultimately successful in halting his efforts to stop Reconstruction-era policies for the remainder of his term. Johnson escaped conviction in the Senate by one vote.

And while the political impact of former President Bill Clinton's impeachment for obstruction of justice and perjury, and subsequent acquittal in the Senate, is hotly debated, top Republicans and Democrats have both argued the proceedings contributed to a bitterly partisan generational tone in Washington.

President Trump, for his part, has warned that a similar effort now would have disastrous consequences.

“If I ever got impeached, I think the market would crash, I think everybody would be very poor," Trump told Fox News in August. "You would see numbers that you wouldn’t believe.”