Fox News Flash top headlines for October 30

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

Colorado voters on Tuesday will weigh in on a ballot measure that could overturn the 2019 decision of their Democrat-controlled legislature and governor to join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPV compact), potentially depriving the movement of the state's nine electoral votes.

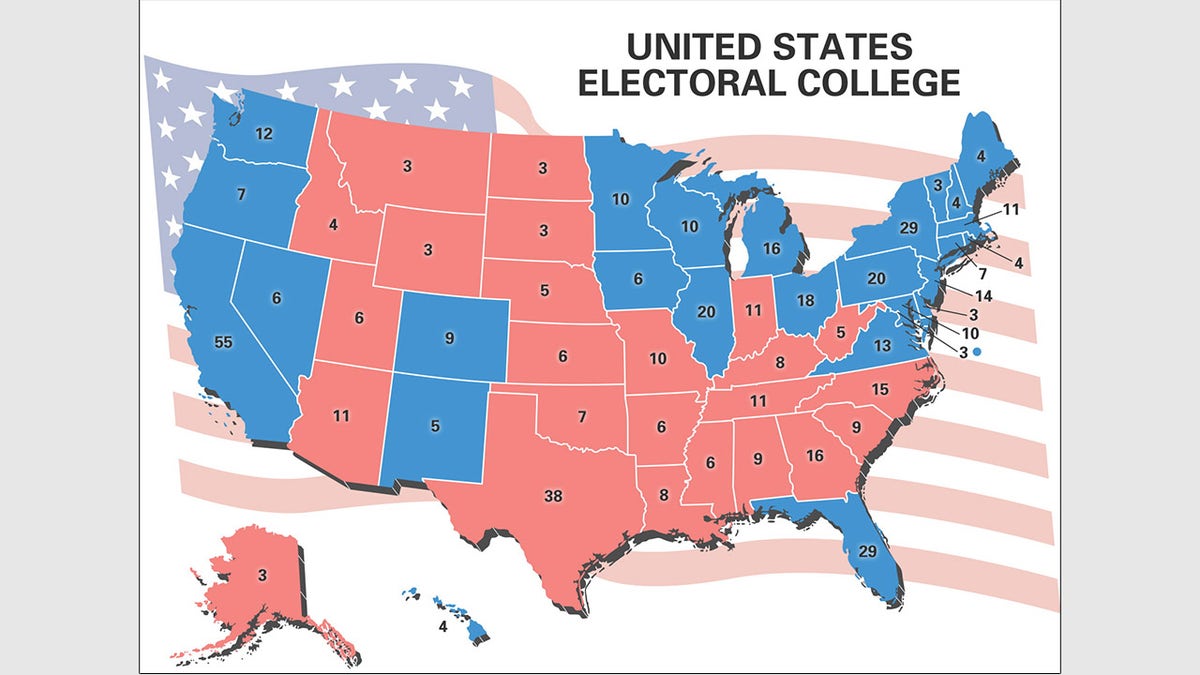

The NPV compact is a group of states that agree, if their coalition grows to include 270 electoral votes, that they will award their electoral votes to the presidential candidate who wins the national popular vote. According to the compact's website, there are currently 15 states and Washington, D.C. that are in the compact, totaling 196 electoral votes.

One of those states is Colorado, which in 2019 passed legislation to join the compact. But voters there will have the opportunity to overturn that law and exit the compact after a group opposing the compact collected more than 225,000 signatures in support of repealing the law.

The vote on Tuesday is the first time a state joined the compact and later had it challenged in a voter referendum. If the law is overturned it would represent a victory for those who support the Electoral College system as it currently stands.

"When the founders came up with the Electoral College, they recognized it as a brilliant compromise that respected the fact that the power comes from the people, but we also have states," Trent England, the executive director of Save Our States, a group that opposes the NPV compact, told Fox News. "It prevented the biggest states or the biggest cities from controlling everything ... it's still true today."

United States electoral college map showing number of electoral votes by state. (Photo by: Encyclopaedia Britannica/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

WHICH STATES HAVE THE MOST ELECTORAL VOTES?

He added: "The Electoral College still makes sure our executive branch is not just run by a handful of big cities or the strips of population-dense areas on the coast. The campaigns are fighting it out across the country in states like Arizona, Nevada and Wisconsin."

If the president were elected by popular vote, those who defend the current Electoral College system say, there would be no motivation for presidential candidates to visit more sparsely-populated areas and they would instead spend their time trying to run-up votes in places like New York City or Los Angeles.

But those who oppose how the Electoral College works today, with a handful of swing states like Arizona, Nevada and Wisconsin playing the most decisive role in the presidential election and thus getting the most attention from candidates, say a popular vote would make every vote important no matter the state.

Saul Anuzis, a senior adviser to the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact organization and former chairman of the Michigan Republican Party, said the current system makes it so most Americans' votes don't matter.

"Four out of five Americans currently live in states that are decidedly Republican or decidedly Democratic," Anuzis told Fox News. "So, they basically don't participate in presidential elections... What happens is instead of electing the president of the United States of America we end up electing the president of the battleground states of America."

Anuzis continued: "It perverts public policy. It perverts politics. If you look at the policy front, battleground states tend to get seven to 10 percent more federal funding than non-battleground states. They're twice as likely to get exemptions from things like No Child Left Behind or anything else. I would submit to you we have ethanol because of Iowa. We passed prescription B because of Florida."

But England argues that the current Electoral College actually reduces that kind of region-centric favoritism and that if there were a national popular vote, it would just encourage a different type of favoritism, but this time in favor of big cities.

"The advantage of a two-step Democratic process is that it prevents regional politics," he said. "It promotes national politics, it forces the political parties to be more national than they would otherwise have to be... by using geography as a proxy for diversity."

But Anuzis argues that politics is often about the margins in individual geographic areas. And with a national popular vote, he said, parties would be incentivized to run up margins wherever they can -- whether red or blue, populated or not populated.

"There's an incentive to campaign in all 50 states," he said. "If you go to a state like Oklahoma or Utah, both of those have, like Oklahoma, had like a 49% voter turnout, I think, in 2012 and Utah was just a little over 50%. Now if all of a sudden you had a reason to turn out voters you'd extrapolate those margins could grow significantly, you'd go after those margins."

An example of this can be seen in how the presidential campaigns are currently approaching Pennsylvania, a critical battleground state. Pennsylvania Democratic Party Communications Director Brendan Welch said in a previous interview about his party's approach to the state that it believes Joe Biden can shrink margins in deep-red parts of Pennsylvania that tipped massively in favor of Donald Trump in 2016.

"I'm not going to pull your leg and say that Joe Biden's going to win these rural counties that Trump cleaned up in," Welch said. "But it's about the margins. Sometimes it's about losing by less."

Pennsylvania Republican Party Chairman Lawrence Tabas, also in a previous interview, expressed similar thoughts, but about Trump's chances in blue urban areas and with minorities.

"We're fighting for every vote in Philadelphia, in the college counties," Tabas said, citing Trump's pre-pandemic economic record on jobs for minorities. "I think we will be better than we did last time... I think the president has big appeal in the African-American, Hispanic, Latino communities, and Asians... And I think you'll find that in Philadelphia, the southeast, we will be a little bit better than in '16."

Each of the parties, of course, has also put a focus on boosting turnout in the areas they traditionally do well in to tip the margins in their favor.

CHRIS WALLACE COMPARES 2020 PRESIDENTIAL RACE TO 1968: 'THIS RACE HAS STAYED REMARKABLY STABLE'

England, however, argues that in addition to boosting a diversity of political viewpoints, the current Electoral College system would contain any vote-counting mishaps to a single state. In 2000 in Florida, for example, only that state's electoral votes were in the balance during the "hanging chad" fiasco. But Anuzis notes that state's electoral votes affected the outcome of the election, meaning that every voter's president was hanging in the balance.

Those who oppose a national popular vote also defend the 2000 election and 2016 election, when Presidents Bush and Trump won the office of the presidency despite receiving fewer votes nationally.

"People talk about 2000, 2016, being, you know 'wrong winner elections,' when really in those elections the Electoral College worked exactly as it was designed to work. There was no misfire," England said. "Trump won by winning over Obama voters in states that Republicans hadn't won for a generation. Whatever else anybody thinks of Donald Trump, he won by playing by the rules that benefit building a broader coalition."

President Trump and Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden are focused on battleground states like Pennsylvania and Florida that could tip the Electoral College. (AP)

Others who are dissatisfied with the way the Electoral College currently works say that a popular vote is not necessarily the only way to fix it. Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig says the "winner-take-all" system used by all states but Maine and Nebraska to allocate their electoral votes is the real problem. It isn't required in the Constitution, but states choose to allocate their votes that way by law.

His group Equal Citizens argues states should distribute their electoral votes proportionally -- similar to how delegates are allocated in the Democratic presidential primary.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

If Colorado voters do overturn their state law and leave the NPV compact, that would bring its total electoral votes down to 187. Some of the largest states in the union, including California and New York, have already joined the compact. Other electoral vote-rich swing states, like Ohio and Pennsylvania, are unlikely to join.

That means the compact would likely need several other states to join before reaching its 270 electoral votes, which it would need to achieve before July 1 on a presidential election year for the compact to go into effect. It could therefore take years for the compact to go into effect, if it ever does.

Currently, nine other states, including Virginia, Oklahoma, Nevada, Minnesota, Arkansas and others, have passed the NPV compact in at least one chamber of their legislature. Virginia, according to both England and Anuzis, is the most active on the compact and could be the next state to join during its next legislative session.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.