In a midterm season marked by primary upsets and the prospect of Democrats claiming a congressional check on President Trump’s power, another sensational development has been the momentum behind a ballot measure to split up the unwieldy, high-tax state of California.

The California secretary of state last month verified almost a half-million signatures collected by Cal3 initiative backer Tim Draper, qualifying it for the November ballot.

But could the seemingly quixotic bid to split California into three separate states become reality?

Californians shouldn’t worry about getting their driver’s licenses redone quite yet – the initiative has plenty of hurdles to surmount, even if it beats the odds and is approved by voters in November.

“There are a lot of what-ifs,” Citizens for Cal3 spokeswoman Peggy Grande acknowledged.

'This is about people who want California to be fixed and saved and this is the way to do it.'

But she maintained the state is “too big to govern.”

“This is about people who want California to be fixed and saved and this is the way to do it,” Grande told Fox News. “We have crumbling infrastructure, dirty water and failing schools. In almost every statistic, 49 states are doing better.”

If the measure does pass, those what-ifs include everything from the impact of litigation to the question of congressional approval to confusion over state-level support.

Lawsuits Likely

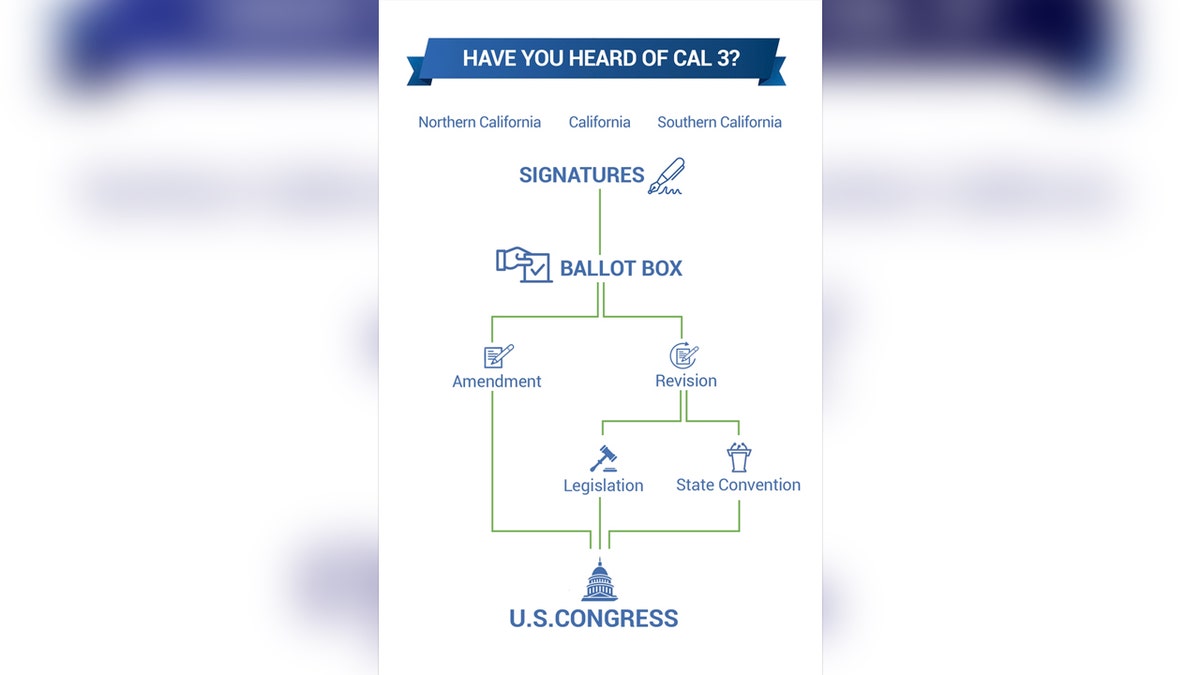

California’s freewheeling initiative process allows voters to enact a law bypassing the state legislature. However, Article 18 of the state constitution makes a distinction between an “amendment” and “revision” to that document.

That distinction could determine whether Cal3, if successful at the polls, is held up at the state level. While an “amendment” would be a relatively minor change that citizens could enact, a “revision” would be a major change requiring either an act of the legislature or a state convention.

Opponents of Cal3 would surely sue to argue it be treated as the latter, said Donald Kochan, an associate dean at Chapman University Fowler School of Law in Orange, Calif.

“California has struggled with this for a while,” Kochan told Fox News.

He said this issue has been at the center of past lawsuits over ballot initiatives.

California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office asserted the state constitution doesn’t explicitly address boundaries or how it would go about splitting into more than one state, adding, “There is no clear precedent for whether a voter initiative may provide the required state legislative consent to split a state.”

Given that uncertainty, Kochan predicted, “Even if Congress accepts these as new states, you would see litigation.”

As Kochan referenced, congressional approval also would be needed for California to split.

Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution states, “no new states shall be formed or erected within the jurisdiction of any other state … without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.” The meaning of this, too, could be up for legal dispute in federal courts, Kochan added.

Congress, in its history, has admitted four U.S. states that split from an existing state: Vermont, Kentucky, Maine and West Virginia.

“There is a factual precedent such as West Virginia, but there have not been court cases to identify a procedure to create a new state,” Kochan said.

Three Californias

Logistically, the Cal3 proposal directs the governor to request Congress grant approval to divide the state into three states: Northern California (including San Francisco), California (including Los Angeles) and Southern California (including San Diego).

On the political front, the makeup of the U.S. House of Representatives would likely stay roughly the same, but the split would give the three Californias four additional U.S. senators, increasing the number of total senators to 104. It also would mean at least four more Electoral College votes in that region.

Both candidates for governor, Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, and businessman John Cox, a Republican, oppose the measure.

If the divide were in effect during the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton would have won all three Californias, according to an analysis by the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia, beating President Trump by more than 30 percentage points in both Northern California and California, and by 10 percentage points in Southern California. However, the same analysis found Democratic President Barack Obama would have narrowly beaten Republican Mitt Romney by 0.6 percent in the state of Southern California in 2012.

While the potential battleground state of Southern California would be an advantage to Republicans who have no chance of winning the current 55 Electoral College votes, the expanded Senate would likely include at least two more safe Democratic seats and two leaning Democratic seats.

Still, Grande insisted, the goal isn’t partisan.

“National politicians only come here to pick our pockets for fundraisers. This will make the three states more electorally relevant,” Grande said. “This is a nonpartisan issue. We have supporters of Cal3 from both sides. This goes across political lines. People are frustrated and disappointed with Sacramento. This is an economic issue not a political issue.”

Breaking Up Is Hard To Do

Though this is the first time the question is on the ballot, the nation’s most populous state has a history of flirting with a break-up – and not actually doing it.

Venture capitalist Draper scaled back his proposal to three this year, after coming up short on gaining signatures for a “Six California” effort for the 2016 ballot. Then there’s the unrelated “Cal-exit,” which seeks to make California a new country.

By some counts, Californians have attempted more than 200 times to divide since statehood in 1849.

As recently as 1992, the state Assembly voted to split the state three ways into North California, Central California and South California. But the idea died in the state Senate. In 1965, it was the Senate that approved a measure for a two-way split into North California and South California, but the Assembly rejected the proposal.

The closest California came to splitting was not long after becoming a state.

In 1859, both legislative chambers approved dividing into California and the Colorado Territory, and the governor signed the bill. But, facing a secession crisis that led to the Civil War, Congress was too busy to take up the matter.

Fred Lucas is the White House correspondent for the Daily Signal.