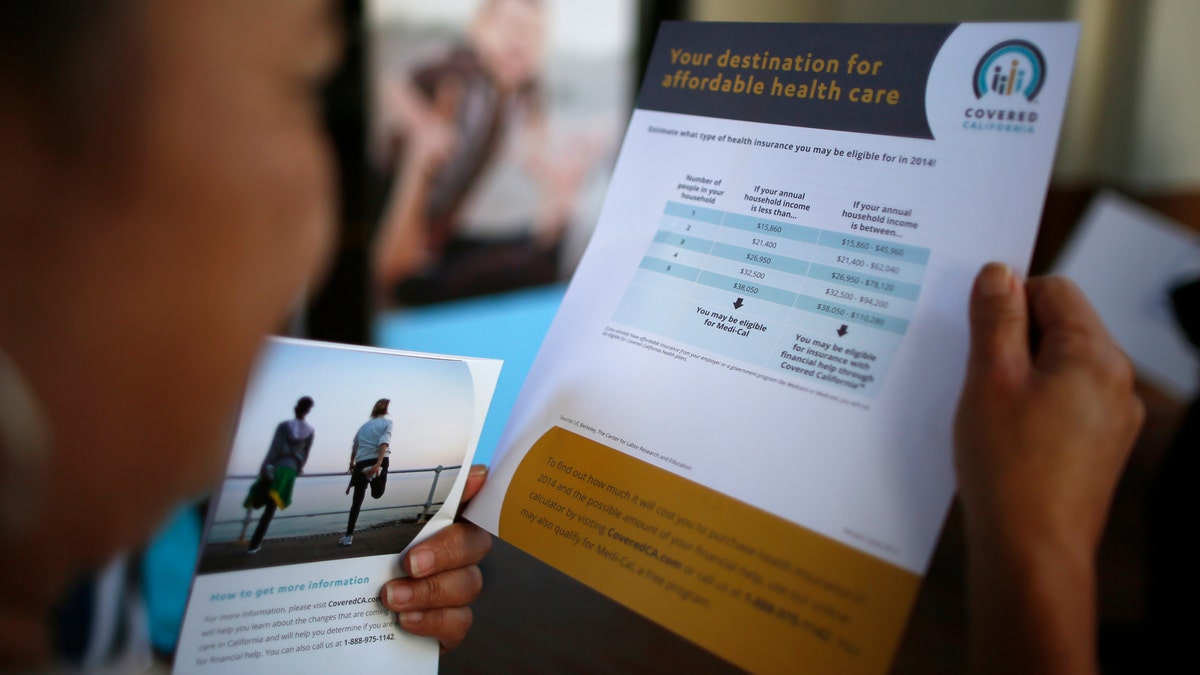

Kay Campos, 56, who has no health insurance and diabetes, browses leaflets at a Covered California event which marks the opening of the state's Affordable Healthcare Act. (REUTERS)

Also...

Two Names Are Enough

Are Media Downplaying ObamaCare Progress—Or Is the GOP Just Giving Up On The Issue?

After a disastrous rollout last fall, ObamaCare has been fading from the news. But is it fading as a political issue?

The fear of those who oppose the program was always that it would be impossible to repeal if enough recipients got hooked on the benefits. That was the hope of advocates as well—that whatever potholes the ObamaCare bus hit, it would keep barreling toward a finish line of getting more Americans insured.

That goal appeared in jeopardy when the administration couldn’t get the website to work. And when the president had to admit that, well, it wasn’t exactly true that if you liked your doctor you could keep your doctor. And when lots of people were kicked off health plans they liked just fine, and faced with big premium hikes. And when the White House delayed the employer mandate yet again. And when many GOP governors refused to sign on to the Medicaid expansion that is a key underpinning of the law.

But now some of the law’s proponents are declaring victory—and the criticism has quieted down. (Sure, John Boehner plans to have the House sue Obama for unilaterally changing the law, but that effort, even it makes it to court, will drag on endlessly.)

As evidence that health care might be losing its punch as an issue for the midterms, the Washington Post reported yesterday:

“This chart, courtesy of the Sunlight Foundation, shows the number of times members of Congress have mentioned the word ‘ObamaCare’ in floor speeches. That point way at the tippy top? That was September 2013, when Congress mentioned ObamaCare 2,753 times. In June 2014, ‘ObamaCare’ was uttered just 171 times. And that's despite Congress having been in session for about the same number of days.

“And it's no coincidence that as the ObamaCare badmouthing died down, some rare good news about the law's first 100 days has started trickling in.”

Indeed, with reports that those without health coverage have shrunk to 13.4 percent of the population, there has been a flurry of headlines like this one in Politico: “The Verdict Is In: Obamacare Lowers Uninsured.”

And in the New Republic: “Obamacare Haters, Your Case Just Got Weaker.”

But what about the expectations? Forbes says that “anyone who says they are certain we have hit the CBO target of a 12 million reduction in the average daily number of uninsured in 2014 has cherry-picked the evidence.”

Paul Krugman, the New York Times columnist and one of ObamaCare’s biggest champions, rips the media for not touting the law’s positive impact. He says that “ an immense policy success is improving the lives of millions of Americans, but it’s largely slipping under the radar…

“The Affordable Care Act has faced nonstop attacks from partisans and right-wing media, with mainstream news also tending to harp on the act’s troubles.”

Krugman says most of those who signed up paid their premiums, and surveys from Gallup and other organizations show “a sharp reduction in the number of uninsured Americans since last fall.” Among those receiving federal subsidies, he says, the average net premium was $82 a month.

“Yes,” he concedes, “there are losers from Obamacare. If you’re young, healthy, and affluent enough that you don’t qualify for a subsidy (and don’t get insurance from your employer), your premium probably did rise.”

His bottom line: “People in the media — especially elite pundits — may be the last to hear the good news, simply because they’re in a socioeconomic bracket in which people generally have good coverage.”

That’s generally true, but some commentators, including Fox’s Kirsten Powers, had their health insurance cancelled because of the new law.

And there are certainly a significant number of losers, as we see in this Forbes piece:

“Economists’ warnings that the employer mandate would encourage some businesses to shift employees to part-time status came true. So did their warnings that government mandates that insurance provide first-dollar coverage for more benefits would raise insurance premiums. Consumers saw that rather than the president’s promised thousand dollars of savings in health care costs, most middleclass Americans are paying more, and often much more. And the impact of those targeted ObamaCare taxes on companies and industries—surprise, surprise—aren’t just hitting those evil one-percenters. It’s middle-class America who is bearing the costs.

“ObamaCare’s tax on tanning salons deserves particular scrutiny, given all the Left’s hand-wringing about an alleged ‘war on women.’ “ Democrats targeted “the indoor tanning industry, singling it out for a 10 percent tax on all UV tanning services sold.

“Women own most tanning salons, make up nine out of ten salon employees, and also account for the majority of their customers. Defenders of the tax argued that the tax would be costlessly absorbed by profitable salons, or passed on to the costumers who had the disposable income to pay a little extra. Yet that’s not how it’s worked in the real world. The industry reports that the number of tanning salons has fallen from 18,000 in 2009 to 10,000 today, and 64,000 jobs have been eliminated in the process.”

The economy could be a factor, course, and those stats include a long period before ObamaCare took effect.

Author and columnist John Fund in the National Review cites another threat to the law, the Halbig case, which was recently heard by a three-judge panel of the federal appeals court in D.C.

“It attacks the central nervous system of ObamaCare — the government exchanges that were set up to subsidize health insurance for low-income consumers. If the Supreme Court ultimately finds that the Obama administration violated the law in doling out those subsidies, it could force a wholesale revision of ObamaCare. In January, The Hill quoted a key ObamaCare supporter as saying that Halbig was ‘probably the most significant existential threat to the Affordable Care Act.’ Jonathan Turley, a noted liberal constitutional-law expert at George Washington Law School, recently agreed, writing in the Los Angeles Times that Halbig ‘could leave ObamaCare on life support.’

“President Obama has increasingly exasperated both judges and constitutional scholars with his boasts about going around Congress when it doesn’t give him what he wants…That attitude has prompted his decision to rewrite ObamaCare at least 23 times without any involvement of Congress. If Obama’s actions in Halbig are found unconstitutional, then other parts of Obamacare will become more vulnerable to legal challenge, and Congress will probably have a much bigger say in rewriting or reversing aspects of the law.”

That could be. But for a long time, conservative opponents of the law pinned their hopes on the Supreme Court, and that didn’t pan out.

Even if advocates like Krugman are overstating the law’s success, its progress in insuring more Americans may be dulling the impact of attacks on ObamaCare. And maybe there’s just ObamaCare fatigue: We have now been battling over this law for 5-1/2 years. Given the scandals and the crises from the Texas border to Iraq, some Republicans may have concluded it’s better for their political health to move on.

Two Names Are Enough

Remember the days of Irving R. Levine? JFK, RFK and LBJ?

A New York Times essay says middle initials are in decline. And I’m glad to hear it.

“Among contemporary presidents, only George W. Bush used a middle initial prominently, and that was a lifelong habit to distinguish him from his father.” The trend was broken, in my view, when we elected a president named Jimmy.

“In 1900, 84 percent of Congress — that’s senators and representatives — used a middle initial. By 1970, the number had dipped to 76 percent. Today, it’s 38 percent.

“Newspapers, like this one, have long been a bastion of middle initials in bylines, so I decided to check winners of the Pulitzer Prize in journalism writing categories, which have been awarded annually since 1917. I randomly chose years ending in zero. In 1920, both winners listed their middle initials; in 1930, two of three. In both 1940 and 1950, half of the individual winners used their middle initial. The percentage ticked down from 43 percent in 1980 to 26 percent in 1990, then held steady at 28 percent in 2000. I skipped 2010 and looked at this year; only one of 12 winners in the writing categories listed a middle initial, the lowest of any of the years I checked.”

Nicholas Kristof dropped his middle initial, saying “It feels a bit ostentatious, even priggish.”

I wouldn’t go that far. But it feels rather stuffy in this age of tweets and selfies.