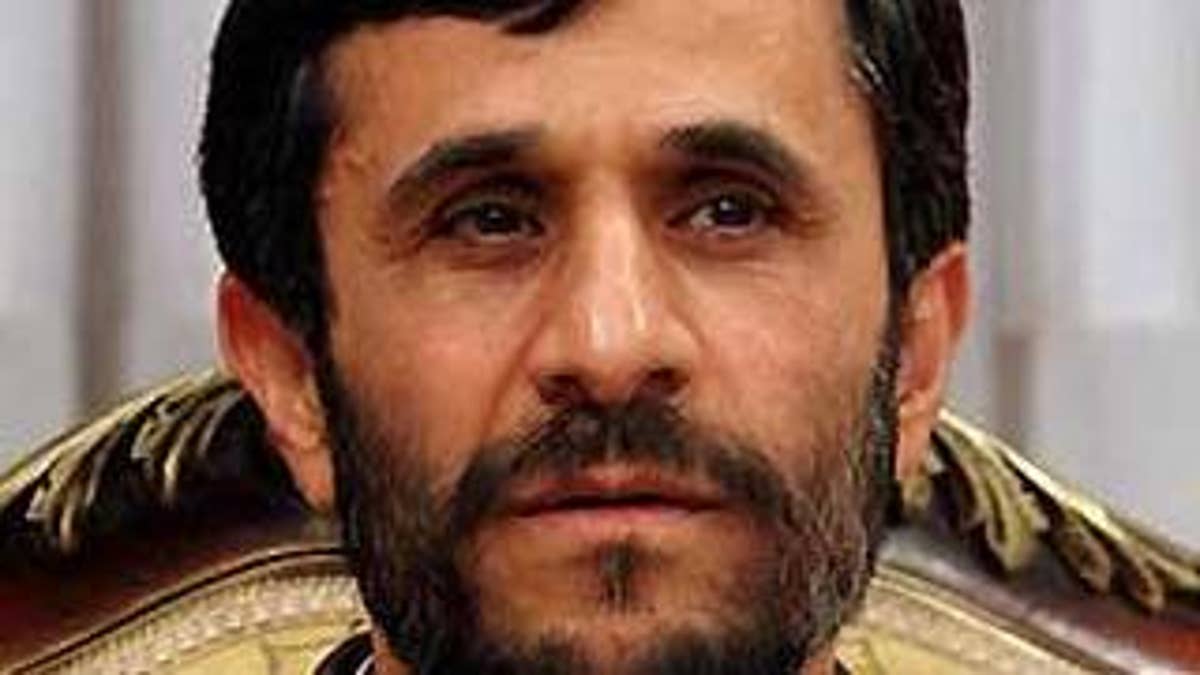

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, with Iran still reeling after his disputed re-election as president, practically dared President Obama on Saturday to take a hard-line approach to the Islamic nation -- pledging a "crushing" response to further U.S. condemnation of the post-election crackdown on protests in Tehran.

The question remains whether Obama will take the bait in this brewing war of words.

The violence after Iran's June 12 election already had thrown into doubt Obama's stated goal of breaking a 30-year diplomatic stalemate between the U.S. and Iran.

Ahmadinejad, with the backing of the country's religious leaders, has been accused by internal opponents of stealing the election through massive fraud. In recent days, he has stepped up his criticism of Obama for demanding an end to the crackdown on dissent.

But analysts in the U.S. said Ahmadinejad's tough talk was less about Obama that it is an attempt to distract the Iranians from the election turmoil.

"I think it is an old habit. When you have nothing to say at home, when you have nothing good to say to people, when you're despised by the people, as Ahmadinejad seems to be, it's always easier to pick a foreign enemy," said Abbas Milani, a research fellow and co-director of the Iran Democracy Project at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

"Shakespeare said it: Keep giddy minds busy with foreign wars," Milani said. "And giddy minds are in fact the Iranian majority who think the election is stolen, and to keep them busy, picking a fight with the United States is always a good idea," he told FOX News.

Ahmadinejad was notorious for his heated rhetoric toward the United States during the Bush administration. He had taken a more tentative approach after Obama's election in November, but now the verbal gloves are coming off.

"You should know that if you continue, the response of the Iranian nation will be strong," Ahmadinejad said Saturday in a speech to members of Iran's judiciary, which is directly controlled by the ruling clerics. "The response of the Iranian nation will be crushing. The response will cause remorse."

Ahmadinejad has no authority to direct major policy decisions on his own -- a power that rests with the non-elected theocracy. But his comments often reflect the thinking of the ruling establishment.

The cleric-led regime now appears to have quashed a protest movement that brought hundreds of thousands to the streets of Tehran and other cities in the greatest challenge to its authority in 30 years. There have been no significant demonstrations in days, and the most significant signs of dissent are the cries of "God is great!" echoing from the rooftops, a technique dating to the days of protest against the U.S.-backed shah before the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Days of relatively restrained talk from both Washington and Tehran appear to be returning to a familiar pattern of condemnation and recrimination, despite Obama's stated desire to move away from mutual hostility. Iran and the U.S. still appear interested in negotiations over Iran's nuclear program, but the rising rhetorical temperature can be expected to slow progress toward a deal, experts said.

"It's premature to judge whether the exchanges between Washington and Tehran totally rule out engagement," said Robin Wright, a public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and an expert on Middle East affairs.

"Clearly events in Iran will make it much more difficult for the Obama administration. But the door hasn't been totally closed yet," she told FOXNews.com.

Obama acknowledged Friday that Iran's violent suppression of unrest would hinder progress, saying, "There is no doubt that any direct dialogue or diplomacy with Iran is going to be affected by the events of the last several weeks."

Obama struck a conciliatory tone toward Iran after taking office, sending a video greeting for Persian New Year that used the government's formal name -- the Islamic Republic of Iran -- in a signal that the goal of regime change had been set aside. He even avoided strong language as Iran first began suppressing street protests, saying he wanted to avoid becoming a foil for Iranian hard-liners who blame the United States and other Western powers for instigating internal dissent.

But Obama decried Iran's crackdown more vigorously as amateur videos of beating and shootings began flooding the Internet. He said Friday, in his strongest condemnation yet, that violence perpetrated against protesters was "outrageous," and dismissed a demand from Ahmadinejad to repent for earlier criticism.

"I would suggest that Mr. Ahmadinejad think carefully about the obligations he owes to his own people," Obama added.

Ahmadinejad appeared self-assured and even invigorated Saturday in the face of the previous day's personal challenge from Obama.

"We are surprised at Mr. Obama," Ahmadinejad said. "Didn't he say that he was after change?" Ahmadinejad told judiciary officials. "They showed their hand to the people of Iran, before all people of the world. Their mask has been removed."

But Wright argued that Ahmadinejad's influence is limited.

"Iran is not a monolithic society any more than the United States," she said. "There are some who will believe Ahmadinejad. I suspect the majority won't."

Ahmadinejad still appeared to leave some opening for dialogue, saying Iranian officials "have expressed our readiness" and still want the U.S. to "join the righteous servants of humanity as well."

Iran had been stopping short of its normally harsh language about the U.S., mostly blaming Britain and even France and Germany as Mousavi's supporters demanded a new election. Ahmadinejad had made relatively few appearances in an apparent attempt to avoid inflaming the situation.

"In fact, they kept him in virtual hiding for the last eight or nine days," Milani said, asserting that Tehran knows how much Ahmadinejad is despised. "So he was in virtual seclusion and he has come out only when he has harsh words to say about the West, particularly about the United States knowing how popular the United States is in fact in Iran."

Experts said, however, that it was not yet certain that Ahmadinejad and his most powerful backer, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, would emerge from the unrest as strong as before. Many speculated that the fight between hard-liners and reformists had moved behind the scenes and would add more uncertainty to U.S. dealings with the already opaque regime.

"There's nothing we can do to affect events," Wright said. "This is where the best course of action is to let the Iranians decide their own future."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.