Trump, Clinton gender swap experiment draws surprise

Strategy Room: Jeanne Zaino and Flip Pidot react to study by New York University

Just before the second presidential debate in October, Professor Maria Guadalupe began to wonder what would happen if the brash, aggressive mannerisms of Donald Trump were emulated by a woman.

Turns out the hypothetical candidate was a hit.

In a bias-challenging twist, Guadalupe and another professor recently engineered a gender-swap exercise featuring a mock debate between a female version of Trump and a male version of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Despite some assumptions that the Trump-ish female would not fare well, audiences actually responded more positively to her.

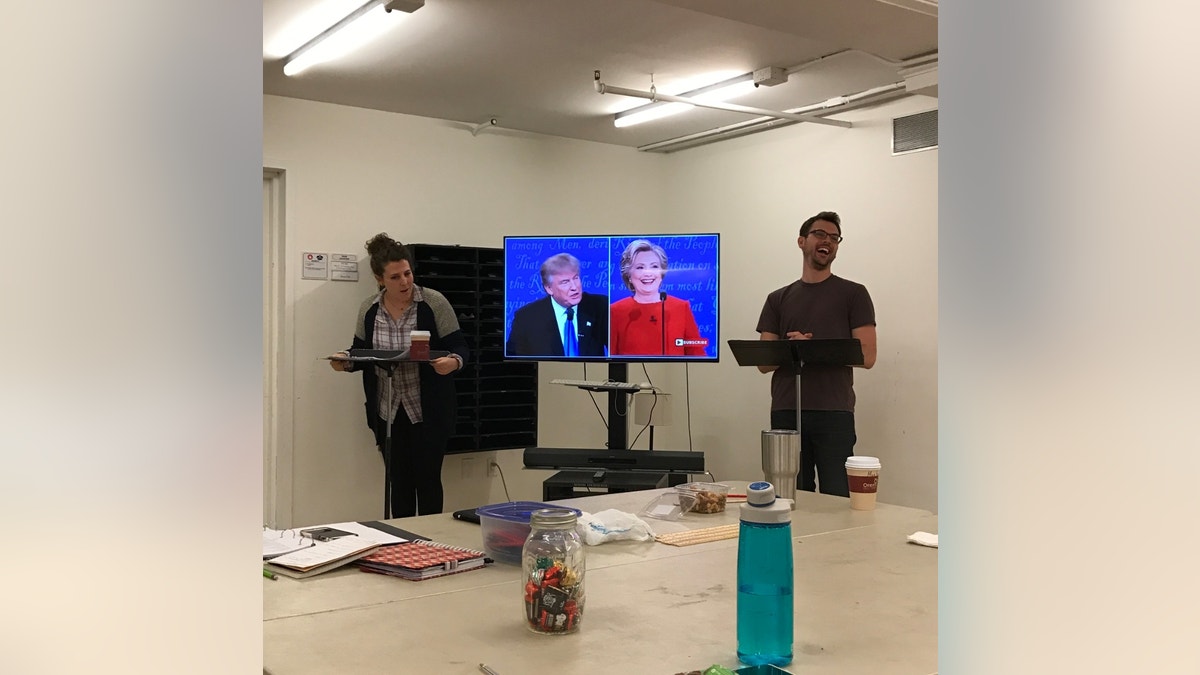

Rachel Whorton, left, and Daryl Embry rehearse for "Her Opponent."

“People were really able to see the techniques that Trump was using,” said NYU Steinhardt clinical associate professor Joe Salvatore, who helmed the project with Guadalupe. “The repetition of a certain idea. The simplicity of a message.

“One audience member described the Trump message as she was able to hear it as hummable lyrics, while Clinton may have had well-researched information, but there was no hook.”

The exercise in Cape Cod may have helped explain the appeal of Trump's message, even though his victory on Election Day was considered one of the great political upsets. While it was staged in late January, Salvatore and Guadalupe are now trying to adapt it into an off-Broadway play and perhaps a film.

The “Her Opponent” project consisted of four sections of verbatim re-creations taken from each of the three debates. Salvatore, who teaches educational theater, called on two actors he’d previously worked with – and who were schooled in learning speech patterns and gestures – to play the critical roles, renamed “Brenda King” (Trump) and “Jonathan Gordon” (Clinton).

Guadalupe, an associate professor of economics and political science at French business school INSEAD, selected scenes that largely featured a back-and-forth between the candidates. The goal was to re-create the most interesting portions – but to leave gender out, thus no references to being “first lady” or the infamous Access Hollywood tape of Trump.

Salvatore stressed the actors were not trying to spoof the politicians; however, they did learn and adopt specific behaviors in order to portray them.

“Clinton has a slight Midwestern accent that comes in and out, so we tried to pay really close attention to that,” Salvatore said. “It really separates her out from the actor, so when Daryl Embry performed her voice with the accent, we could hear her more.”

Taking on Trump presented unique challenges for actress Rachel Whorton.

“For Trump, he uses his voice in a way where he goes into his lower register,” Salvatore said. “He sort of goes into a gravely place in his voice and, obviously, when a woman is working in that, it won’t go as low.”

Then there were the infamous Trump hand motions.

“He’s got three or four different finger configurations – there’s no real rhyme or reason as to how he uses them,” Salvatore said.

Before the performances in late January at the Provincetown Playhouse, audience members were issued surveys and asked to list three positive and negative attributes of the candidates as they remembered them from the debates. After the 35-minute show was over, they were asked the same question about what had just occurred. The post-debate results were illuminating.

“They liked that [Whorton] was more passionate,” Guadalupe said. “Genuine. Emotional. People were connecting with her emotionally. They didn’t listen so much to the content. She was just really committed and passionate about what she was saying.”

Said Salvatore: “I’ve never been in a post-performance discussion where people were so articulate.”

The experiment gave Guadalupe a new appreciation for how she understands and views genders, whether in the political realm or not.

“It’s not just candidates,” she said. “When I see a woman presenting, I see it differently. Academic setting, business, at dinner – how men and women behave. I think this is all applicable to how we see each other.”

Salvatore said he voted for Clinton and during the course of rehearsals found himself questioning his own inherent biases and perceptions.

“While we had ideas about what we thought might happen,” he said, “we were also open to the idea that different things could happen.”