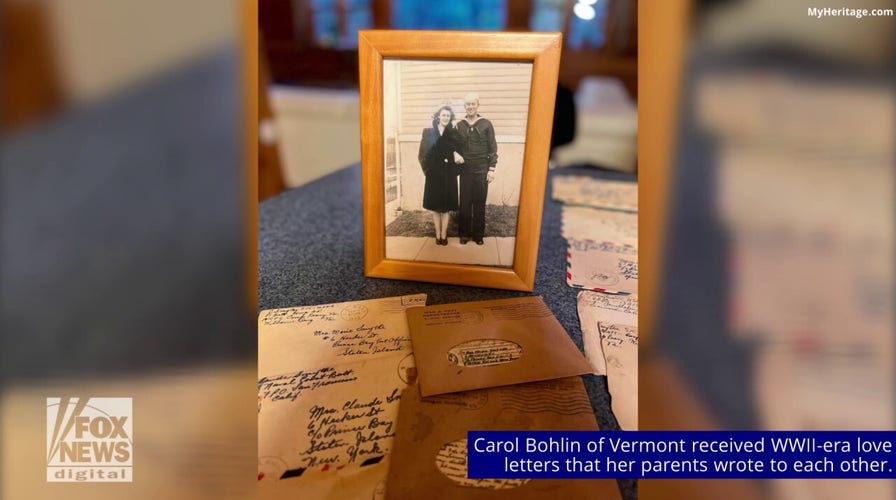

Vermont woman receives cache of World War II-era letters written by her parents

Carol Bohlin of Vermont, 75, received a package of letters that her parents sent to each other while her father was serving in the U.S. Navy nearly 80 years ago. Watch her read aloud from these remarkable letters that had been hidden away in a wall.

Editor’s note: On April 9, 1942, during World War II, approximately 10,000 American and 62,000 Filipino soldiers laid down their arms on the Bataan peninsula, Philippines, and became prisoners of war. Allied troops were rounded up and marched 66 miles up the peninsula toward prison camps in what became known as the Bataan Death March. The following is adapted from the forthcoming novel "THE LONG MARCH HOME," written in tribute to the troops who were there.

Ten hours after the attacks on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army attacked the Philippines.

For the next four and a half months, American and Filipino troops fought back with fury. Much of the Navy had been destroyed at Pearl Harbor, so without the support of ships, and with their backs against the sea, the troops in the Philippines were doomed to fight without reinforcements or new supplies. Courage abounded, but the troops were inexperienced, outgunned, and outmanned, and soon faced starvation and tropical diseases.

At last, Army Major General Edward King issued the unthinkable order to surrender on Bataan. On that dark April day, some 10,000 American soldiers and 62,000 Filipino soldiers dropped their weapons and were taken prisoner. It was the largest ever surrender of American troops. (A handful of Allied troops would keep fighting for another month under General Jonathan Wainwright on the tiny island of Corregidor, off the coast of Bataan.)

BATAAN SURVIVOR, 101, REMEMBERS ENDURING POW CAMPS BECAUSE ‘GOD SUSTAINED ME

As a culture, Imperial soldiers had been indoctrinated to show no mercy for Allied soldiers, particularly those who surrendered. Random beatings, shootings, throat-cuttings and other unspeakable horrors left a trail of the dead. Although the exact count is lost in infamy, historians estimate some 6,000 to 10,000 men died on the march alone.

Some reached the destination: prison camps that became places of starvation, beatings, disease, and death. POWs were put on work details, often to bury dead bodies, carry water, or grow crops, but the resulting food benefited only enemy troops. Allied prisoners received some medical care, sporadically-delivered mail from home, and occasional Red Cross packages, but whether a man lived or died at the camps became anybody’s guess.

After enduring the prison camps of Bataan, some Allied prisoners were packed into freighters, which set out to cross to Japan, another kind of ordeal. Locked in the holds, with little food or water and no sanitation facilities, some men went insane in the "Hell Ships," as they were called.

OLDEST BATAAN DEATH MARCH SURVIVOR, BEN SKARDON, DEAD AT 104

Some prisoners drowned. The Japanese ship, Arisan Maru, among others, gave no notice that prisoners were aboard. She was sunk by an American submarine and took down with her more American prisoners than had died at Camp O'Donnell. A rough count suggests that more than 5,000 Americans died when Allied Forces unwittingly bombed or torpedoed the hell ships.

For those who arrived on the mainland, life was no easier. Beatings, sicknesses, shortages, atrocities, and horrific methods of torture ensued as Allied troops worked in enemy war effort factories and hard labor camps.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

By war’s end in August 1945, approximately one in three of Japan’s Allied prisoners of war did not make it home. For the men who had surrendered on Bataan and lived, it had been 41 months of pure hell.

The Philippines sets aside every April 9, called Day of Valor, or "Araw ng Kagitingan," as a day to commemorate the valor of the Allied forces on Bataan. In the United States, April 9 has been called "National Former POW Recognition Day" since 1987.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Each spring, civilians and military personnel gather at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico to commemorate the Bataan Death March. The memorial honors the heroic troops who defended the Philippines during World War II, who laid down their freedom, health, and often their lives.

May they never be forgotten.