54 percent drop in refugees coming into the US

Does this statistic prove President Trump's immigration order is working?

“And if a stranger sojourn with thee in your land, ye shall not vex him. But the stranger that dwelleth with you shall be unto you as one born among you, and thou shalt love him as thyself.” Leviticus 19.33-34

Think about how it would feel if you had to leave your home, right now, quickly, without much of a plan because delay might mean death. Now, go! Where will you go?

Your friends and neighbors have to leave their homes too, so you can’t just sleep on their floor or their couch until the crisis blows over. All of you have to go. And take with you only what you can stuff into a bag, and carry in your hand or on your back.

Of all your things to take, which are most important? Clothes? Food? Money? You face hard choices. But the hardest is where to go. Who will have you? A nearby village, state or country?

We decided to say, “Hello. We don’t know how this is going to work out, but you come to church with us and we’ll figure it out together.” And so, two wildly different peoples with different cultures, languages, customs, worldviews, and experiences began worshipping alongside one another.

It seems like nobody wants people in your situation anymore. Self-preservation dictates many communities can’t welcome you because you pose a threat to their comfort, security, livelihood, the character of their neighborhoods, churches, schools, places of work.

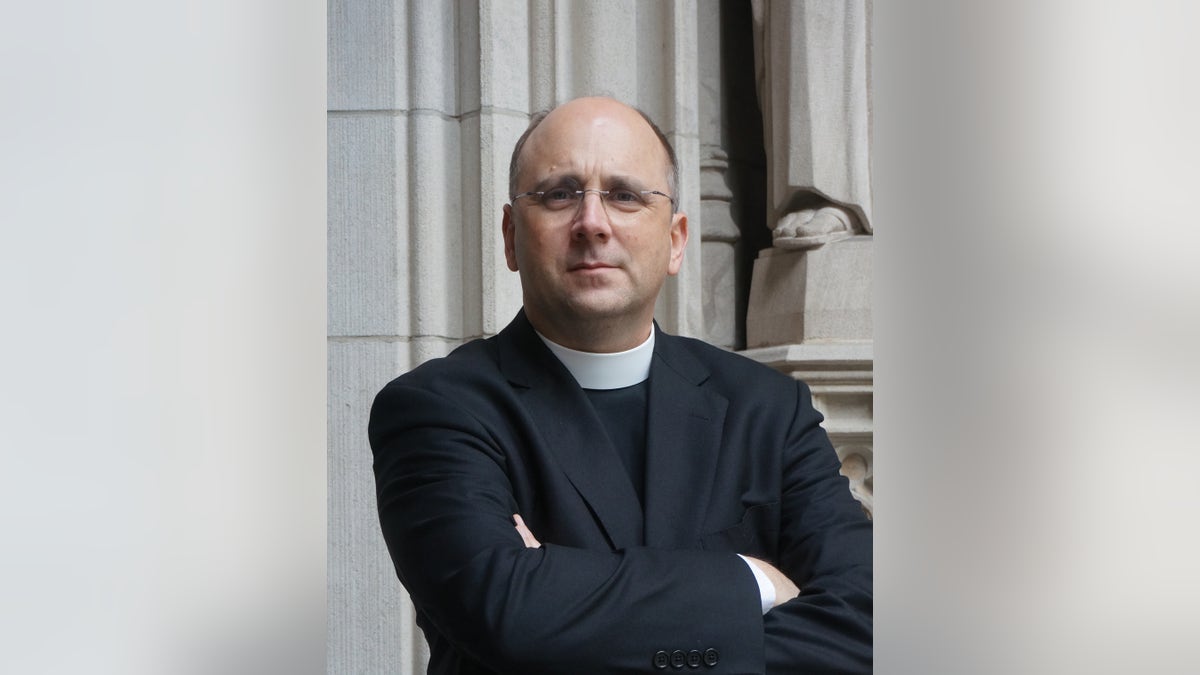

I am a parish priest, and I don’t pretend to understand refugee policies or legislation on national, state or even on local levels. But I do know what refugees are.

First, they are human beings; human beings forced to leave their nations, their homes, because of natural disaster, war, or persecution.

It is probably the case that most refugees don’t want to leave, but to stay places them in mortal danger. They flee to be safe and to protect their families. Their greatest difficulty is not leaving their homes, as painful as that may be. Their greatest difficulty is finding a place to go. Who will have them?

In 2008, while priest of an Episcopal church I feared would be sold due to low attendance and crippling debt, a community of Karen refugees from Burma arrived at our service one Sunday saying they would like to attend our church, and needed help with food, clothing, transportation, medical care, and employment.

Their needs, at first, seemed overwhelming in the face of my congregation’s paucity of resources and the impending loss of our church. I was counseled by well-meaning colleagues not to take on this community of refugees, as they would sink an already vulnerable church. As well-meaning as they were, I couldn’t help but think their counsel was cynical, faithless even.

We decided to say, “Hello. We don’t know how this is going to work out, but you come to church with us and we’ll figure it out together.” And so, two wildly different peoples with different cultures, languages, customs, worldviews, and experiences began worshipping alongside one another.

In time, we began living and then thriving with one another. While we were immediately and spontaneously welcoming, I did have concerns whether or not a relatively conservative, semi-rural congregation of mostly white southerners would be receptive to such a dramatic and foreign change to the face of their church community, and how this might even change the face of the town they lived in.

I didn’t have any control over the latter, but I did bear some responsibility for the former. In the vast majority of cases I needn’t have worried.

In the isolated instances where my fears were well founded, such as when one member told me she “just wanted to go to church with people who looked like her” and another who had “brown people fatigue,” I caught a glimpse of unvarnished racism that led to their departures from the church.

It was their loss, because what they missed out on was better than anything they could imagine for themselves or find in a more “like them” congregation.

I am no longer the minister at All Saints Church in Smyrna, Tennessee, but today it is one of the larger Episcopal churches in the area, and it continues to grow, debt free.

The Karen are beginning to see their children graduate from college, and their quality of life is steadily improving. The locals who welcomed them in have seen their lives enriched by sharing their own lives and experiences with the Karen, which have helped them better acclimate. They have also helped many to become citizens, which is a source of pride shared by Anglo and Karen alike.

My experience at All Saints didn’t teach me much about refugee and immigration policy. It did teach me that while I don’t have control over who shows up on my doorstep, I do have control over my response to them, if and when they arrive.

I learned that “Hello” is a good place to start and though you won’t necessarily know how things are going to work out, you may just find that figuring it out together brings peace and wellbeing for everybody.