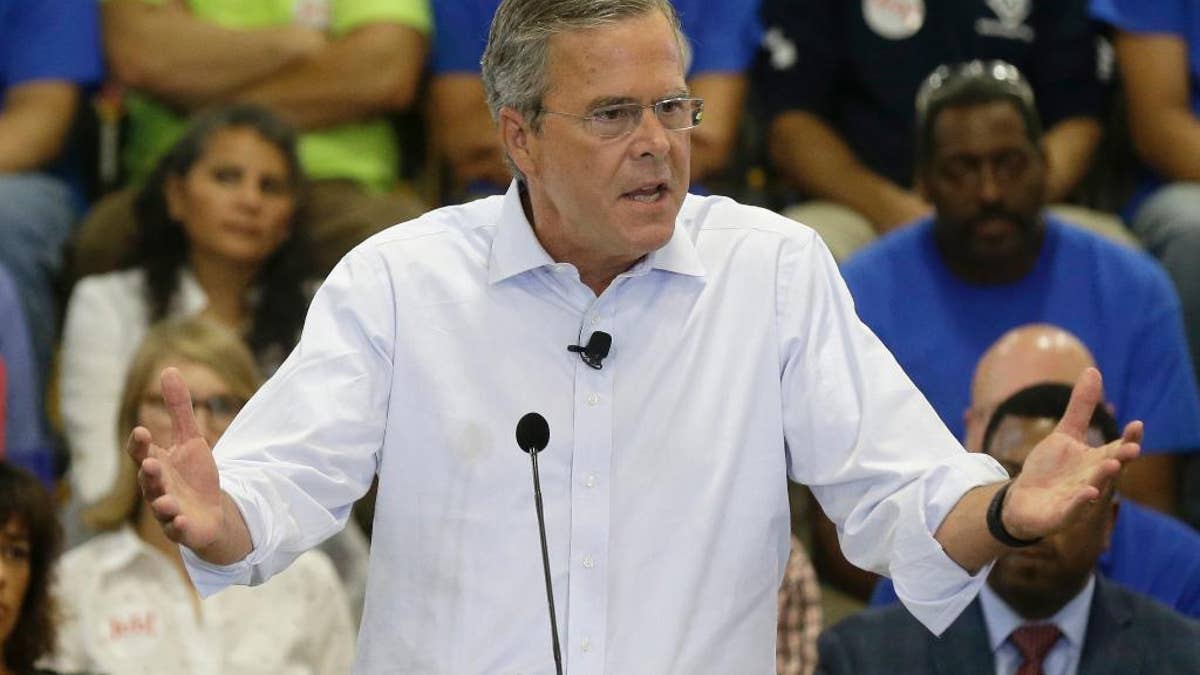

In this photo taken Sept. 9, 2015, Republican presidential candidate, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush speaks in Garner, N.C. To some Republican presidential candidates, it’s better to be with the popular pope than against him. (AP Photo/Gerry Broome) (The Associated Press)

The supporters of Governor Jeb Bush’s tax reform proposal have called it “radical.” In an important sense, this is an accurate characterization, because the reform would be a dramatic departure from the status quo. It’s also radically different from the tax reforms typically presented by presidential candidates. As opposed to the usual vague generalities, this plan is detailed and includes tough calls that will likely irritate some special interest groups.

There is another sense, though, in which the plan is anything but radical, because it is based on tenets that have informed the thinking of proponents of good tax policy for centuries. Let’s see how Governor Bush’s plan stacks up against the principles for taxation that were set forth by Adam Smith in "The Wealth of Nations" more than two hundred years ago.

Given that he was a Professor of Moral Philosophy, it’s no surprise that Smith’s first principle dealt with fairness: The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities.

Governor Bush’s proposal is a coherent and principled blueprint for building a better tax system.

Smith is arguing that everyone should pay the same proportion of his or her income. The Bush proposal follows Smith’s general principle that tax liabilities should increase with income. However, following most modern commentators on tax policy, the Bush proposal goes beyond Smith by stipulating that the proportion of income paid in tax should increase with income. Indeed, several aspects of the plan enhance progressivity relative to the status quo, such as the limit on deductions that benefit mostly high-income individuals.

Smith next turns to the importance of transparency: The time of payment, the manner of payment, the quantity to be paid, ought all to be clear and plain to the contributor, and to every other person. Where it is otherwise, every person subject to the tax is put more or less in the power of the tax-gatherer… By subjecting the people to the frequent visits and the odious examination of the tax-gatherers, it may expose them to much unnecessary trouble, vexation, and oppression.

Our current tax system is so complicated that even people who want to be honest don’t know if they are paying the right amount and live in fear that they will be subject to “the odious examination of the tax-gatherers” (sorry, IRS auditors). For example, think about all the head scratching that goes on when individuals are trying to figure out just what expenditures are deductible.

The Bush proposal expands the standard deduction and puts limits on sums that can be itemized, thus reducing the need for most taxpayers to deal with these issues. For businesses, complying with the incredibly complicated rules governing depreciation is expensive and time-consuming. By allowing firms to deduct the cost of capital expenditures at the time they are made, the Bush proposal attenuates the “unnecessary trouble, vexation, and oppression” caused by the depreciation rules.

Smith next turns his attention to the importance of minimizing the economic damage done by taxes: Every tax ought to be so contrived as both to take out and to keep out of the pockets of the people as little as possible over and above what it brings into the public treasury of the state. Smith notes several ways in which a poorly designed tax system can violate this maxim.

One is that “it may obstruct the industry of the people.” High marginal tax rates, which reduce the rewards to working and saving, are certainly a culprit here.

The centerpiece of the Bush proposal is a substantial reduction in marginal tax rates. Smith also warns against tax systems that discourage people “from applying to certain branches of business which might give maintenance and employment to great multitudes.”

Smith understands that disincentives to invest in businesses punish not only entrepreneurs, but also workers. The Bush proposal reduces effective tax rates on all types of businesses, which would increase investment, employment, and economic growth.

Smith concludes by noting that “The evident justice and utility of the foregoing maxims have recommended them more or less to the attention of all nations.” Unfortunately, the virtue of Smith’s maxims has apparently not been at all evident to policymakers in recent years. Governor Bush’s proposal is a coherent and principled blueprint for building a better tax system. I think that Adam Smith would approve.