The Pacific, 1942: They were young men, a year removed from their stateside fraternity houses and university lecture halls.

Charles "Red" Kendrick spent his 16th birthday in the shadow of Stanford’s Hoover Tower, a child prodigy fluent in seven languages. Before he moved on to Harvard, he pledged Sigma Nu.

Delta Tau at Miami University counted lean-faced Yale Kaufman among its brothers. Yale also played football and track at the school.

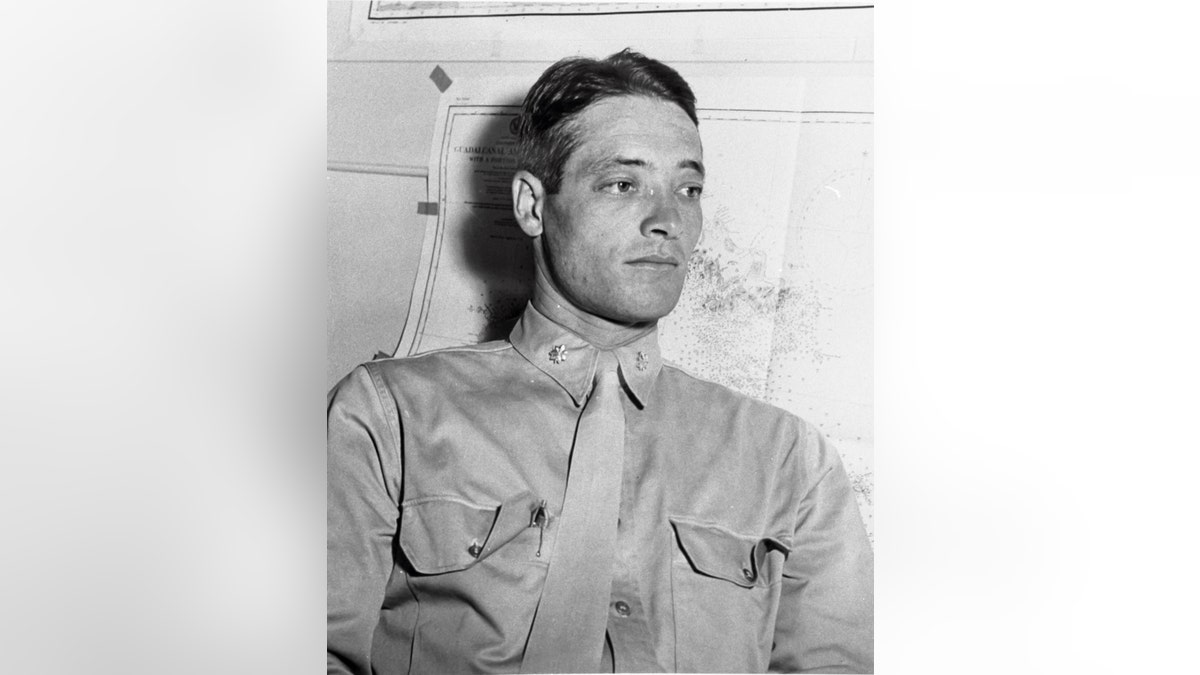

John L. Smith, left, Richard Mangrum, center, and Marion Carl, seen at NAS Anacostia on Nov. 10, 1942, before a Life magazine photographer captured Smith's ruggedness while in the cockpit of an F4F Wildcat. That photo made the cover of Life and forever enshrined the Oklahoma native as one of the greatest early war heroes to emerge from the Pacific. (National Archives)

Dick Mangrum, the oldest and wisest of them, had been in Phi Delta Phi at the University of Washington before he went on to law school, and a decade-long flying career.

ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, NOVEMBER 12, 1942, NAVAL BATTLE OF GUADALCANAL BEGINS IN THE SOLOMON ISLANDS

The Navy turned them into aviators. Since they all had been in the top 10% of their flight cadet classes, they received, and accepted, offers to become Marines.

They never went through boot camp. Parris Island was unknown to them. Their logbooks showed only a few hundred hours of flight time in training aircraft. Until a month before, hardly any of them had flown a frontline combat aircraft.

In the summer of 1942, this handful of fraternity boys-turned combat pilots formed the tip of the aerial spear in America’s first offensive of World War II: Operation Watchtower, the seizure of Guadalcanal Island in the Southern Solomons from the Japanese.

On Aug. 7, 1942, the Navy put the 1st Marine Division ashore on Guadalcanal, then bugged out with only a portion of their supplies ashore. The Marines captured the vital airstrip on the island and set up a defensive perimeter around it, hoping the Navy would return.

John L. Smith was a young captain without much time in fighters when he was given command of the newly formed VMF-223 shortly before the Battle of Midway. In the months that followed, his squadron’s ranks were filled with hastily trained pilots with little experience flying fighters. The Corps gave him less than a month to forge these raw citizen-warriors into an effective combat force. (National Archives)

THE DAY AN 18-YEAR-OLD MARINE HIT THE GUADALCANAL BEACH AND HELPED TURN THE TIDE OF WWII

The seas around Guadalcanal were owned by the Japanese that August. So was the air. Raiding Japanese bombers pounded the Marines almost every day. Without fighters of their own, or dive bombers to stop the Japanese warships offshore, all the Marines could do was hunker down and absorb the punishment.

Kendrick, Kaufman, Mangrum and the other 41 aviators were sent to Guadalcanal on Aug. 20, 1942, told by their senior officer, Lt. Col. Charley Fike, that their mission on the island would be to "buy time with your lives" until the Navy could bring in reinforcements.

Two squadrons, the fighters of VMF-223 led by Capt. John L. Smith, and Maj. Richard Mangrum’s dive-bombers of VMSB-232, totaled 31 aircraft. They faced hundreds of Japanese planes crewed by airmen who’d been shooting down planes while most of these Americans had been playing JV ball for their high schools.

The Marines had 30 days to train in their combat aircraft. The Japanese they faced had been in combat since 1937.

US MARINE HONORED POSTHUMOUSLY IN MASSACHUSETTS FOR HEROICS AT GUADALCANAL

The experience disparity had led to disaster every time Marine aviation fought the Imperial Navy. At Pearl Harbor, the Marine squadrons at Ewa Field were wiped out on the ground. At Wake Island, a tiny Marine fighter squadron fought gallantly – but was quickly wiped out. The survivors reported as infantry and fought on the beaches until the garrison surrendered.

The ground crews at Henderson Field established themselves as some of the most devoted, selfless men on the island. They worked under miserable conditions with virtually no equipment, sometimes taking artillery or small arms fire, to keep the available aircraft flying. Most had been in the military for less than a year. These men of the 67th Fighter Squadron worked under the added burden of not having any tech manuals for their unit’s Bell P-400 Airacobras. (USMC)

At Midway, the Marine fighter squadron lost 19 of its 25 aircraft in 60 minutes of combat. Their brothers in the dive bomber squadron lost three skippers in three missions, and over two-thirds of the squadron went down attacking the Japanese fleet.

The odds of survival on Guadalcanal were not good. The night they reached the island and hunkered down under tarps in the jungle, the Japanese launched their first ground assault against the perimeter. They awoke to sniper fire and Japanese machine guns shooting at them as they took off on their first missions.

Back home they’d been called spoiled, soft, more interested in girls and kegs than the foreign affairs that ultimately threw them together in this war. But at Guadalcanal, they showed the measure of their mettle.

WW2 VETS FROM 'THE PACIFIC' REMIND TODAY'S GENERATIONS TO PUSH THROUGH DIFFICULTY

They flew every day, sometimes two or three missions from an airfield under small arms and artillery fire. Without the Navy bringing in the beans and bullets, they slowly starved on captured stocks of Japanese rice and canned fish. The pilots, already lean and fit, lost upwards of 30% of their body weight.

There was no refuge from combat. They lived in the jungle in deplorable conditions. They were shelled and sniped constantly. One of John L. Smith’s fighter pilots was hit by a sniper while bathing in a nearby stream.

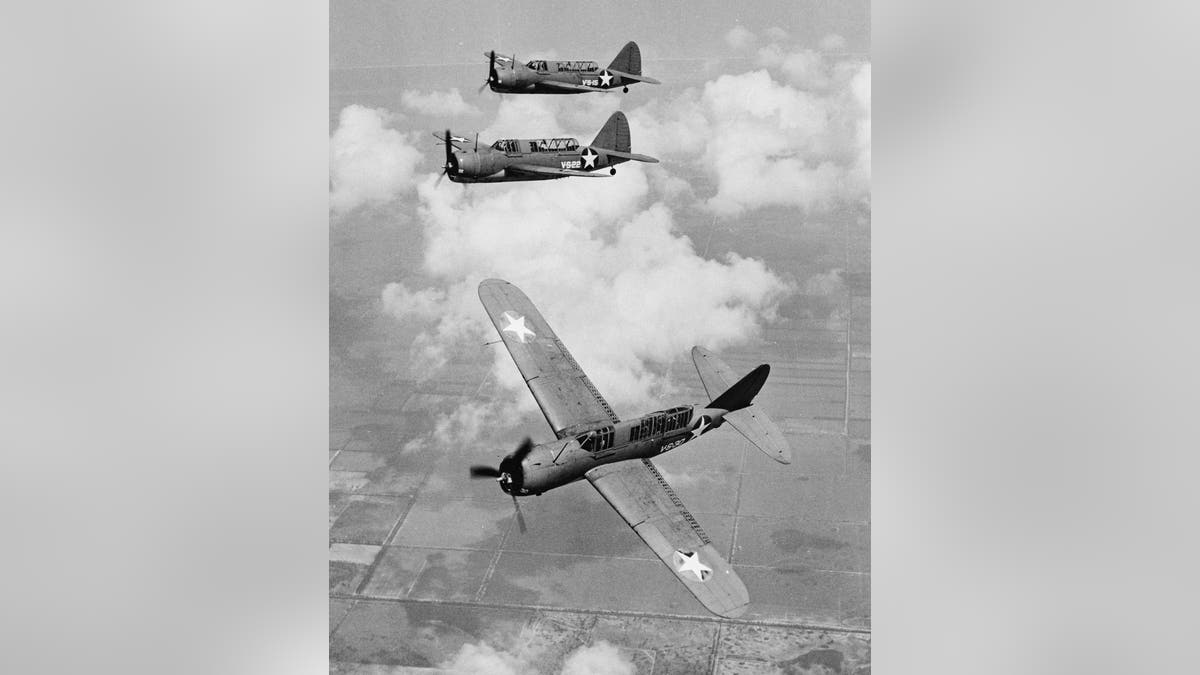

Dick Mangrum test-flew the Brewster SB2A Buccaneer, and the Navy counted on it to replace the aging SBD Dauntless VMSB-232 at Guadalcanal. But one flight convinced Dick the SB2A was a dog. The Navy ultimately relegated it to training duties only, and the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver would eventually take the SBD’s place during the final year of the Pacific War. (John Bruning, authors collection)

Some nights, Japanese warships bombarded them with devastating naval gunfire. Others saw night intruders slide overhead, guided by moonlight to drop bombs and deny the men desperately needed sleep.

They climbed into their cockpits every day to face the Japanese, knowing they’d face an enemy superior in every way – except pure grit. All of them fell victim to a cornucopia of tropical diseases: dysentery, malaria, dengue fever – and a host of others unknown to Western medicine at the time.

GUADALCANAL – WHEN THE BEST DEFENSE WAS A BOLD OFFENSE

Still, they rose to meet the Japanese. John L. Smith led them into battle, his leadership and skills as a fighter pilot was their ace in a hole. He inspired not just his squadron, but all the Marines on the island, who watched him tear into the tormenting Japanese bombers with singular fury and skill. The Japanese shot him down. He hiked back through the jungle and found another cockpit and kept fighting.

He’d earn the Medal of Honor for his time on Guadalcanal.

Inevitably, the college kids-turned combat aviators began to die. Yale Kaufman was caught in his dive bomber, low and slow as he came back to Guadalcanal to land. An unseen enemy fighter strafed his cockpit, a fan of blood sprayed the plexiglass – and his plane went straight into the water. No survivors, and he and his gunner were never recovered.

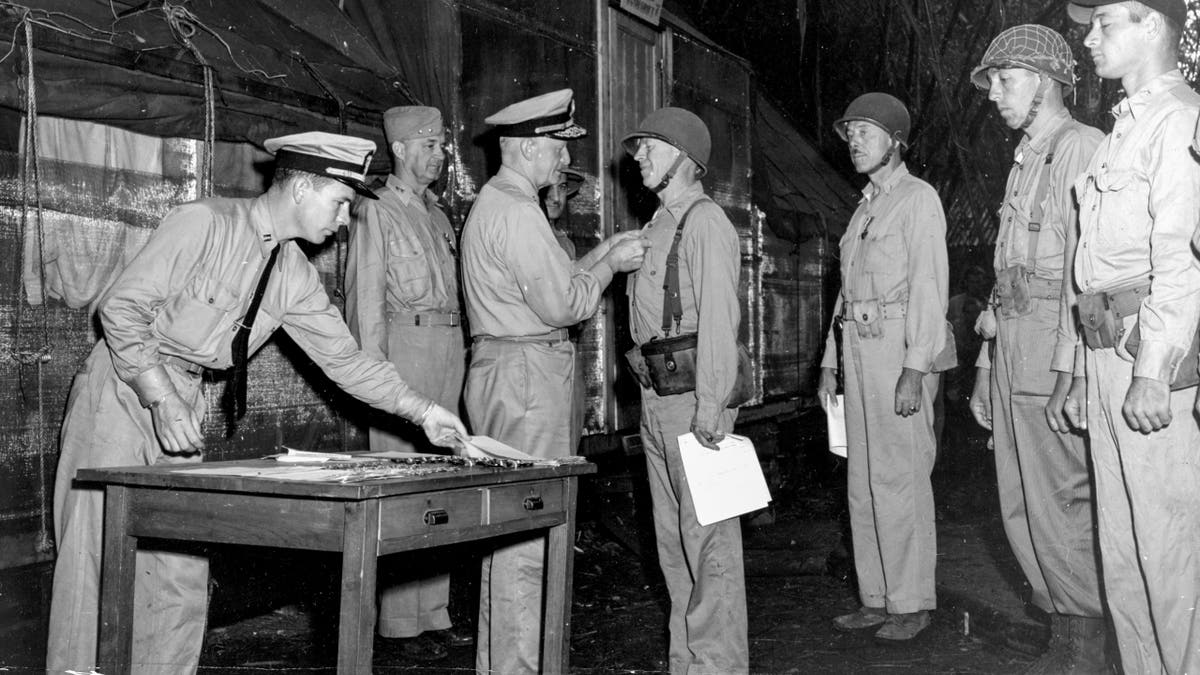

Adm. Chester Nimitz presents awards to some of Guadalcanal’s defenders during a short visit to the island on Oct. 1, 1942. At far right is John L. Smith, who received a Navy Cross along with Marion Carl and VMF-224’s skipper, Robert Galer. To the shock of these men, Dick Mangrum received a Distinguished Flying Cross, a lower award. Nimitz had run out of Navy Crosses to give. The apparent snub affected morale and the ceremony was not well remembered. Within days, several of the men honored that day would be killed in action. (USMC)

Red Kendrick, the Stanford prodigy, became a favorite of Smith’s. Cool in a fight, quick to learn, he’d been shot up and wounded several times but always dragged his fighter home – and always got back in the cockpit the next day. On Oct. 1, 1942, Adm. Chester Nimitz personally awarded Red the Distinguished Flying Cross.

A few days later, Red Kendrick’s luck ran out. He vanished in an aerial ambush that cost Smith his Rutgers grad, Willis Lees as well.

GUADALCANAL, 1942: RARE PHOTOS OF THE PACIFIC OFFENSIVE

Fifty-three days after arriving on the island, Smith and his eight surviving pilots were mercifully withdrawn from Guadalcanal. Richard Mangrum was the last pilot standing from VMSB-232. The others had all been killed in their air or by bombardments, wounded or medically evacuated due to disease.

They’d executed their mission. They defended the American flag on Guadalcanal and bought time with their lives for more planes and pilots to reach the island and carry the fight forward. It came at a terrible cost – to both the green Americans and the Japanese. For all the damage these fraternity boys-turned-Marines absorbed during those 53 days, the Japanese suffered worst.

John R. Bruning's "Fifty-Three Days on Starvation Island" is a detailed account of the Marine aviators first sent into Guadalcanal, as seen through the eyes of John L. Smith, Richard Mangrum and first Marine ace Marion Carl.

Smith’s men were credited with shooting down nearly 90 aircraft, most of them bombers. Mangrum’s men turned back two critical Japanese convoys and later killed over 300 enemy troops as they made their way to Guadalcanal in barges and landing craft.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

They didn’t just buy time, they stopped a superior enemy cold and helped foil the first major counteroffensive on the island, later dubbed the Battle of Bloody Ridge. Their service and sacrifice electrified the homefront and inspired countless others to join the ranks of Marine aviation.

Eighty years later, the frat bros at UNC Chapel Hill and Ole Miss protected the American flag from anti-Israel protesters. These weren’t outlier events, but a continuum of a tradition of patriotism and service that spans a century.