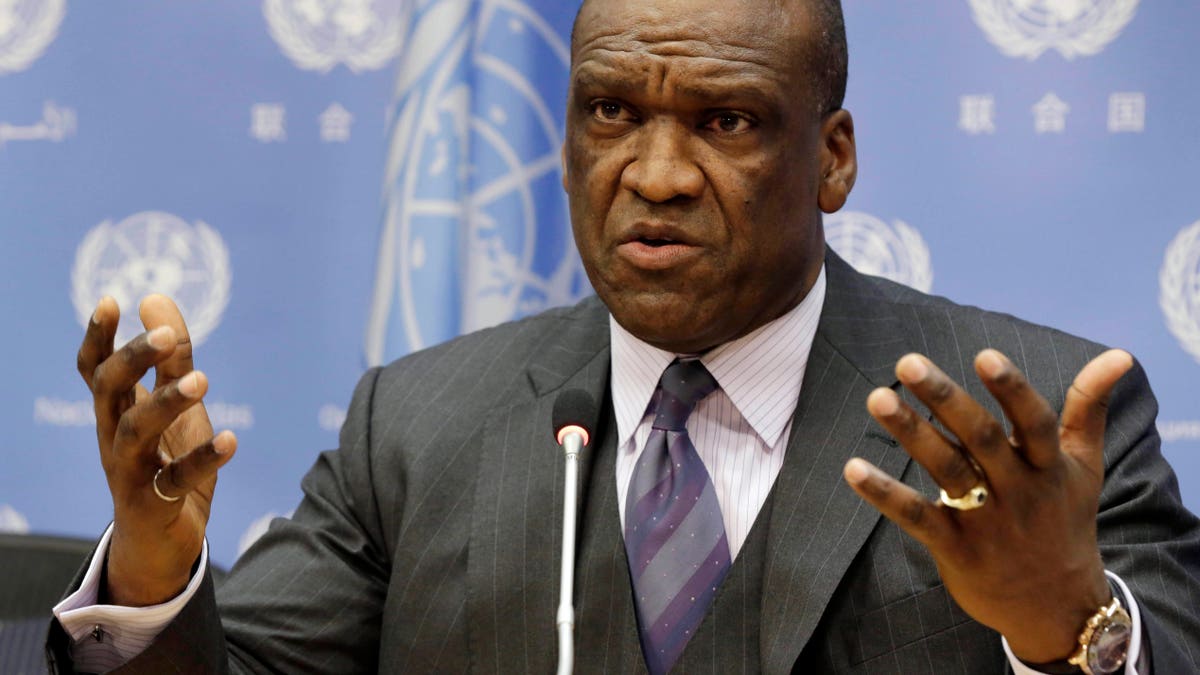

FILE - Sept. 17, 2013: Ambassador John Ashe, of Antigua and Barbuda, the president of the General Assembly's 68th session, speaks during a news conference at United Nations headquarters. Ashe accepted more than $500,000 in bribes from a Chinese real estate mogul and other businesspeople in exchange for help obtaining lucrative investments and government contracts, according to federal court documents unsealed Tuesday, Oct. 6, 2015.

This week, U.N. Spokesman Stephane Dujarric told journalists that “corruption was not business as usual at the U.N.” After an almost two-year stint there as Under Secretary General for Management, I beg to differ.

Corruption at the United Nations—evidenced by the arrest this week of John Ashe, former president of the U.N. General Assembly, on bribe-taking charges—shouldn’t surprise anyone. The fact that the U.N. has largely walked away from the tools needed to do anything about it is the real scandal.

I had been at the U.N. for only a couple of weeks in 2005 when the chairman of the U.N. budget committee, a senior Russian diplomat, was arrested for taking bribes. For me, it was a shocking introduction to the institution. I would soon know better.

In the ensuing months, we began to try to change the culture and bring meaningful accountability and financial controls to the U.N. in the wake of the Oil for Food scandal. It became clear the organization was thoroughly rife with corruption.

The U.N. must not be a poster child for bad governance, inadequate internal controls, and minimal transparency. It should be the first, not the last, place to embrace best-in-class practices.

There was also a massive denial mentality at the place, which made any reform difficult. When I proposed creating an ethics office and ethics training for senior officials, a senior Arab diplomat told me, “We do not need ethics training here, Chris. The U.N. only hires ethical men.”

In fact, ethical behavior at the U.N. requires rare courage.

Three days after joining the U.N., a senior career employee of the U.N. asked to see me. Entering my office she told a story of corruption, intimidation, and suppression, and I wondered—what have I gotten my self into. After she left I asked my staff, “Who is she?” A number of staffers told me she was reputed to be crazy.

That is exactly how “Ostrich Organizations” deal with whistle blowers. They try to scare them off through intimidation, and when that doesn’t work, label them “mentally unstable,” and then they stick their collective head back in the sand.

Due to that woman’s courage, four people were charged with corruption and sent to jail, including a senior official nominated to be head of all U.N. procurement.

Soon thereafter, with the support of then-Secretary General Kofi Annan, we launched the Anti-Corruption Procurement Task Force (PTF), led by a tough former Assistant U.S. Attorney, Robert Appleton, who tenaciously began to root out corruption across the organization.

Before the Anti-Corruption Taskforce was killed, it had discovered potential worldwide corruption in U.N. logistics and peacekeeping operations, and fraud that appeared to rise to the highest levels of the diplomatic corps in a multitude of member states.

But in the end, as Appleton closed in on senior diplomats and U.N. officials, two national delegations --the Russians, and, strangely, the Singaporeans—successfully lobbied to prevent renewal of the task force mandate and funding.

At that point, in 2008, meaningful internal investigation into wrongdoing at the U.N. ended.

On paper, the U.N. still has the means to police itself, at least to some degree. There is a legacy “Inspector General,” called the Office of Internal Oversight Services, which investigates waste and wrong-doing. But that office lacks true strength and independence, and has virtually no ability to conduct independent criminal investigations.

Thus, it is up to host nation law enforcement efforts -- in the Ashe case, the U.S. Attorney for the New York Southern District -- to ferret out corrupt U.N. officials and diplomats and put them in jail.

The latest scandal could be an opportunity to make important changes that would put the proper policing function back in U.N. hands.

Secretary General Ban Ki-moon’s term of office ends in less than a year. He should sincerely try to emulate his predecessor, Kofi Annan, who in his last eighteen months in office tried desperately to strengthen U.N. accountability.

At a minimum, the organization should establish truly independent outside audits of its operations, and annual audits of internal controls. The U.N.’s current Board of Auditors should stop its ridiculous reliance on borrowing government auditors from member states to conduct biannual audits of the U.N.

Instead, it should do what the U.S. government does, and contract with independent outside firms to provide real audits under the International Public Sector Audit Standards—the same standards the European Commission uses.

The U.N.’s Office of Internal Oversight Services should be made completely independent of the Secretary General and report to the chief justice of the new Internal Justice System.

A separate, independent oversight office should be established to investigate and conduct internal audits of all U.N. peacekeeping operations. The head of the office should be appointed for a ten-year term, just like the head of the FBI.

A proposed Office of Access to Information, otherwise known as a freedom of information office, was killed after Russian lobbying in 2006. It should immediately be established to bring, for the first time, real transparency to all U.N. operations.

Finally, the Anti-Corruption Taskforce should also be reestablished with another tough former federal prosecutor leading it —just as before.

The U.N. must not be a poster child for bad governance, inadequate internal controls, and minimal transparency. It should be the first, not the last, place to embrace best-in-class practices.

The U.N. is supposed to set an example for the world. It badly needs to set a better one.

Christopher Bancroft Burnham was Chief Financial Officer of the U.S. Department of State from 2002 to 2005, and Under Secretary General of the United Nations for Management from 2005 to 2006.