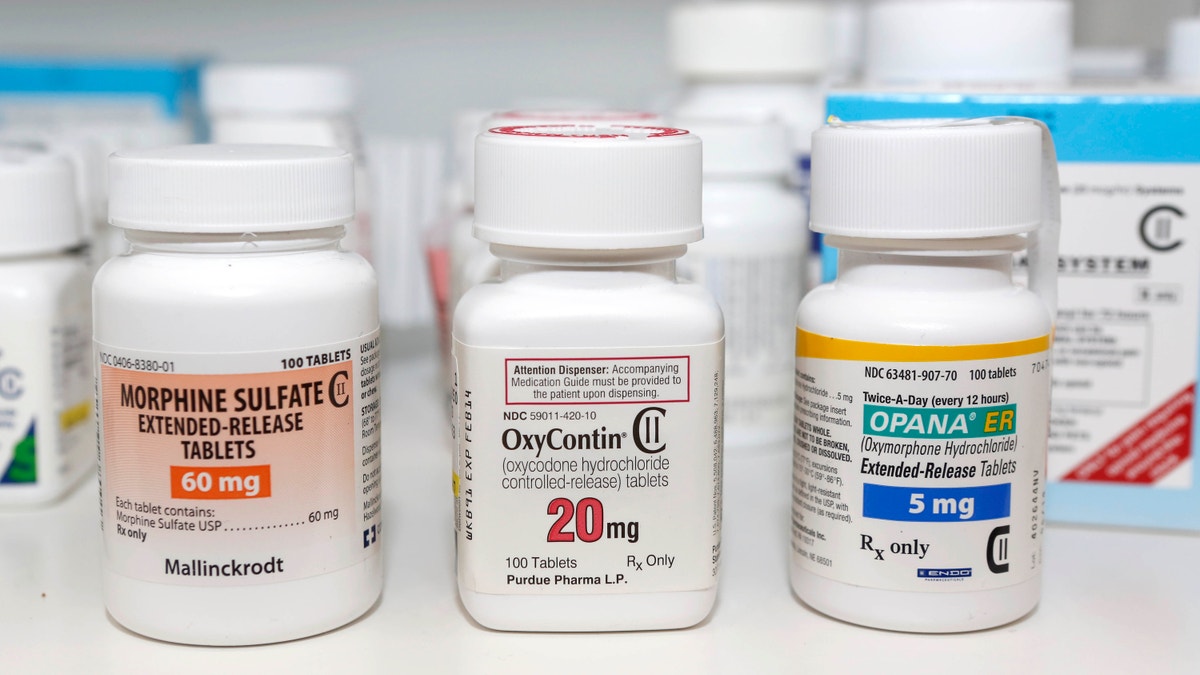

FILE - In this Jan. 18, 2013 file photo, Schedule 2 narcotics: Morphine Sulfate, OxyContin and Opana are displayed for a photograph in Carmichael, Calif. California doctors will be required to check a database of prescription narcotics before writing scripts for addictive drugs under legislation Gov. Jerry Brown signed Tuesday, Sept. 27, 2016, that aims to address the scourge of opioid abuse. (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli, File) (Copyright 2016 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.)

My new patient didn’t mention his back pain until the very end of the visit. As he was rising to leave, he asked casually if I could refill his Percocet. I told him I am not a pain or a back specialist and that I generally prescribe muscle relaxants or anti-inflammatory medications for back pain — not opioids, which are addictive and do not really treat the underlying problem.

The patient persisted. He said his prior internist always prescribed it, and the medication also helped his mood. He promised he had its use under control and did not feel he needed to take more and more to achieve the same effect.

I didn’t relent. I offered to refer him to a back specialist instead. It was an uncomfortable end to an otherwise positive visit.

According to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control, over 50,000 Americans died from drug overdoses in 2015, more than from automobile accidents or shootings. Eighty percent of these overdoses involved opioids, including not just heroin but Vicodin and the Percocet that my patient was asking for. CDC also reports that the death rate from synthetic opioids besides methadone increased 72 percent in the U.S. between 2014 and 2015.

Unfortunately, we doctors are enablers. Too many of us fill those prescriptions for chronic pain. And when we don’t, too many of our patients leave us for other doctors who will. Or worse, they turn to buying heroin on the street.

And opioids aren’t the only drugs where there is a blurred boundary between medical and recreational use. Medical marijuana is now legal in 28 states plus Washington, D.C. And while there certainly are legitimate uses for cancer treatment, nerve pain and even the spasms of multiple sclerosis, increased access without strict justification has become pervasive.

This trend sets a poor example for opioids, where overuse of Vicodin and Percocet lead to increased heroin use. According to the CDC, patients addicted to painkillers are 40 times more likely to become addicted to heroin.

The bottom line: Opioids should not be first-line or routine therapy for chronic pain that is not due to cancer. Hopefully, help is on the way. In 2014 the DEA clamped down on hydrocodone (including Vicodin) by placing it in the more restrictive Schedule II category, and several states, including New York, have instituted systems that require logging all narcotics prescriptions into a state website. West Virginia even allows opioid addicts to sue prescribing doctors.

Finally, Congress just passed President Obama has just signed the 21st Century Cures Act, which includes a focus on mental health parity and addiction and includes $1 billion to fight the opioid epidemic.

CDC released data a week ago revealing that Americans are now living 78.8 years on average, down a tenth from a year ago. Accidental deaths due to opioids are one reason for the decline.

Consider that opioids like Vicodin, Percocet, Fentanyl and heroin suppress breathing, and that you can easily slip over the line from safe to life-threatening if you are auto-medicating, especially when you increase the amount you take to achieve the same effect.

The 21st Century Cures Act is only the beginning. We need more funding and more restrictions and more counseling of both doctors and patients. In the doctor’s office, we need to change our focus to alternative treatments, including muscle relaxants and physical therapy.

Chronic pain is real, but we need to understand and treat the pain-generator, rather than overmedicate the brain. The wrong choice can kill.