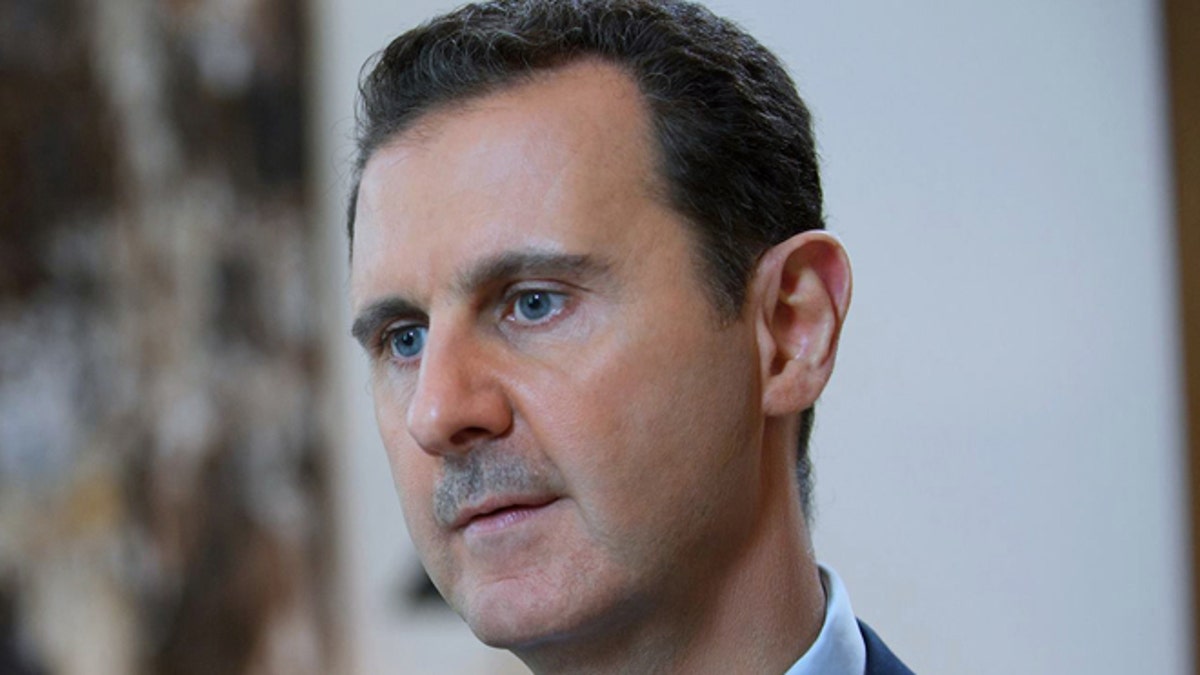

Oct. 4, 2015: Syrian President Bashar Assad speaking during an interview with the Iran's Khabar TV, in Damascus, Syria. (AP/SANA)

The person essential to resolving the Syrian tragedy was not invited to Vienna. Syrian President Bashir al-Assad stayed in Damascus while representatives of 17 countries, the U.N., and European Union gathered in the Austrian capital to discuss his country’s fate.

For a moment, those assembled last Friday appeared to recognize the urgent need for a coordinated international strategy to end the war that has devastated an entire country, with extraordinary repercussions beyond its borders.

The P5+1 -- U.S., Russia, China, Britain, France, and Germany – the group that had achieved the deal with Iran on its nuclear program were present. So were Iran and the Arab countries -- Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates -- that have direct stakes in the outcome of the Syria conflict.

His first trip abroad should have been to the Palace of Justice in The Hague, which houses the International Criminal Court (ICC), where he could have been compelled to accept responsibility for his crimes against humanity.

But seven hours of talks turned out to be mainly symbolic. A communiqué attempting to convey at least some degree of progress presented a consensus view that “the Syrian people will decide the future of Syria,” and that the U.N. will facilitate a ceasefire and a political process to restore stability and rebuild the country.

Good luck with that. The U.N.’s envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura, has already faced the same frustrations with Assad that led his two predecessors, Kofi Annan and Lakhdar Brahimi, to resign in despair. Assad, the ophthalmologist turned dictator, has never been a leader open to dialogue with opponents.

The conflict has only emboldened his appetite for control and destruction, which has already left more than 300,000 dead and millions of refugees, with more dying and fleeing every day.

Even as the talks were taking place in Vienna, the Assad regime exhibited its evil once again with a deadly air attack on a Damascus suburb not far from the site of the 2013 chemical weapons attack it carried out with impunity.

Assad rarely leaves his Damascus sanctuary to travel within his own country, and has gone abroad only once since the conflict began in March 2011. That happened last month when Russian President Vladimir Putin welcomed Assad to Moscow soon after Russian forces intervened in Syria to support him.

His first trip abroad should have been to the Palace of Justice in The Hague, which houses the International Criminal Court (ICC), where he could have been compelled to accept responsibility for his crimes against humanity. Moscow, however, has blocked the UN Security Council from referring Assad to the ICC, just as it has hindered any other meaningful council steps regarding the conflict.

Incredibly, the official statement that emerged from the Vienna talks did not even mention Assad. It is important to recall that this humanitarian disaster began 55 months ago not because of external forces. Rather, it was set off by a harsh regime’s brutal response to schoolchildren who, inspired by Arab Spring protests across the region, had scrawled anti-Assad graffiti, and then were detained and tortured.

That truth, so critical to understanding the roots of the conflict and why Assad must be deposed, has been largely sidelined by the focus on combating the Islamic State, or ISIS. On this issue there was agreement in Vienna: ISIS, the communiqué stated, “must be defeated.”

But how can ISIS be effectively fought in a coordinated way without first addressing the original conflict in Syria? After all, ISIS emerged amidst the chaos created by the Assad regime’s brutal bombardment and destruction of Syrian cities and towns.

Russia is carrying out bombing missions ostensibly focused on ISIS, and the U.S. will be sending 50 military “advisors” to provide on-the-ground assistance to the Syrians. But a singular focus on ISIS diverts attention from Assad.

Without addressing Assad’s role in the crisis and planning for an alternative leadership, it will be hard to marshal the unity necessary to dislodge and replace him, and to establish a degree of stability in those regions of Syria not under ISIS influence, all of which are prerequisites to taking on that terrorist demon.

The U.S. administration was right several years ago in demanding that Assad step down. That demand should be reasserted now with renewed vigor and energetically impressed upon Moscow, as well as Tehran.

To save Syria in any form, Assad must go.