Most recent polls show that one-third of Americans don’t know much about the Affordable Care Act, or ObamaCare. The law’s rollout began on October 1. Now, it pays to review some basic questions that many Americans will have about the law, and clear up some misconceptions.

1. Is ObamaCare a government takeover of insurance?

(Reuters)

Political bluster aside, the health care law does not create a single-payer health care system like the United Kingdom or Canada. Neither does the law dictate how much doctors can be paid or set price controls on things like prescription drugs or medical devices.

But the law certainly increases government involvement in health care. The core of the law established “health insurance exchanges” or marketplaces, in every state around the country plus Washington, D.C.

These marketplaces are where Americans without coverage (or with coverage that is unaffordable), can shop for health insurance. The plans available will be run by private insurance companies.

Where the federal and state governments step in, however, is in dictating how these plans can be priced and what services they have to cover.

For starters, insurers will be barred from charging older applicants more than three times what they charge the young; they will also be prohibited from denying coverage to anyone; lastly, the law limits what people can pay in “out-of-pocket” spending like deductibles and co-pays.

In addition to dictating how insurance plans can be priced, the federal government set a minimum standard of “essential health benefits” that all insurance plans sold on the exchanges have to cover – there are 10 benefits in total and they include things like preventive services (annual physicals for instance) and mental health services. Some states like New York have chosen to add additional benefits to the federal minimum – adding costs as well.

2. Will I pay more for insurance?

Get Covered America buttons are seen during a training session in Chicago, Illinois September 7, 2013 before volunteers canvas a Chicago neighborhood to talk with residents about the Affordable Care Act - also known as Obamacare. (Reuters)

As with many things dealing with ObamaCare, the answer is “it depends.” The health care law institutes a controversial “individual mandate” which requires all Americans to purchase health insurance.

Depending on your current insurance status and your income, the law may decrease costs, leave them as they are, or increase them. For people who receive insurance through their employers (more than half of the country) and work full-time, the law does little to affect monthly premiums.

For people who get coverage through government programs like the Veteran’s Administration, Medicaid, or Medicare, the law also doesn’t change much.

The biggest effect will be on those who currently buy insurance on their own (between 10 and 15 million people) and the uninsured (about 50 million people).

Generally speaking, people buying coverage on their own will see their premiums increase. In a study of 13 states plus Washington, D.C. with my Manhattan Institute colleague, Avik Roy, we found that premiums for this group will increase by 24 percent on average (see the results in this interactive map).

The cost increase largely comes from the newly required benefits and limits on how insurers can price their products.

The newly insured, however, will fall into three groups – those with incomes low enough to qualify for the law’s Medicaid expansion (below $32,500 for a family of four); those with higher incomes that are low enough to qualify for federal subsidies; and those whose incomes are too high to qualify for subsidies.

People who end up receiving Medicaid coverage will pay little-to-nothing for their insurance, but will tend to have poor access to doctors.

People who buy insurance on the exchanges, and who are eligible for subsidies, will receive some federal assistance with paying their premiums, but the costs may still be prohibitive.

Lastly, those with incomes greater than $94,000 for a family of four or about $46,000 for an individual will receive no federal help and will see costs increase significantly.

While it’s hard to say how many people will fall into each group (since people can choose to opt-out by paying a small penalty), it seems ever more likely that premiums under ObamaCare – even with subsidies – will be greater than they are now.

3. How much will health insurance cost me?

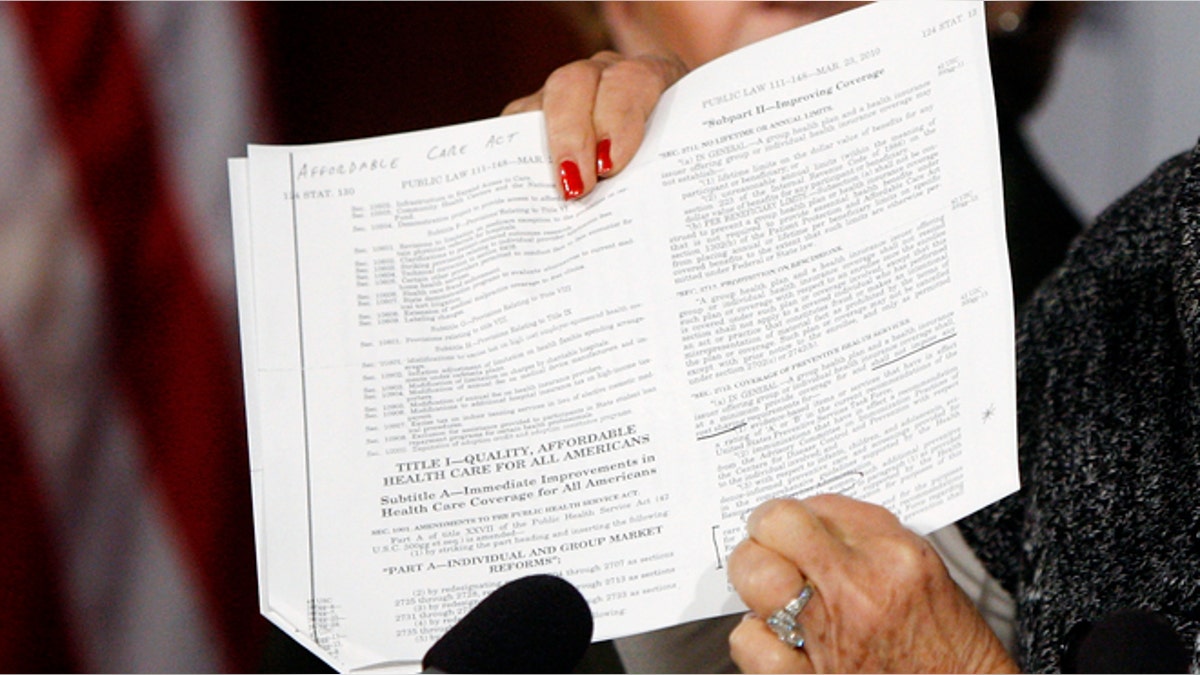

U.S. Senator Barbara Boxer (D-CA) holds a copy of the Affordable Care Act (commonly known as Obamacare) at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, September 30, 2013. (Reuters)

If you’re one of the people that ends up buying insurance on one of ObamaCare’s exchanges (estimated to be around 7 million in 2014) how much you pay for health insurance will depend on several factors.

For instance, health insurance costs vary quite a lot around the country. The cheapest plan in Arizona would cost you $141 per month in premiums; on the other hand, it’s a whopping $254 in Arkansas.

Then come the subsidies. If you’re the typical 20-something around the country, you likely won’t get much in the way of subsidies – on average, you might get $20 to help foot the bill. Of course, if you’re lower income – say, a family of four living on $50,000 – family coverage could cost you as little as $72 a month in Missouri.

Readers should also bear in mind that there’s more to the cost of health insurance than just the monthly premiums.

The cheapest plans on the exchanges will have deductibles (the amount you have to pay before insurance kicks in) ranging from $4,000 to $6,000 for individual coverage – about twice that for family coverage. This means that for insurance to cover many services (except the “essential health benefits” outlined earlier), you’ll have to spend between $4,000 and $6,000 out of your own pocket first.

To make the most of these high-deductible plans, anyone buying coverage on the exchange will need to work with their insurance company to help set up a health savings account (HSA) that will allow them to deposit pre-tax dollars for help with covering these out-of-pocket costs.

Now that the rollout of ObamaCare has begun, consumers need to understand how the law affects them. The majority of Americans will be marginally affected. Those who do get coverage through the law, however, will face a slew of changes.