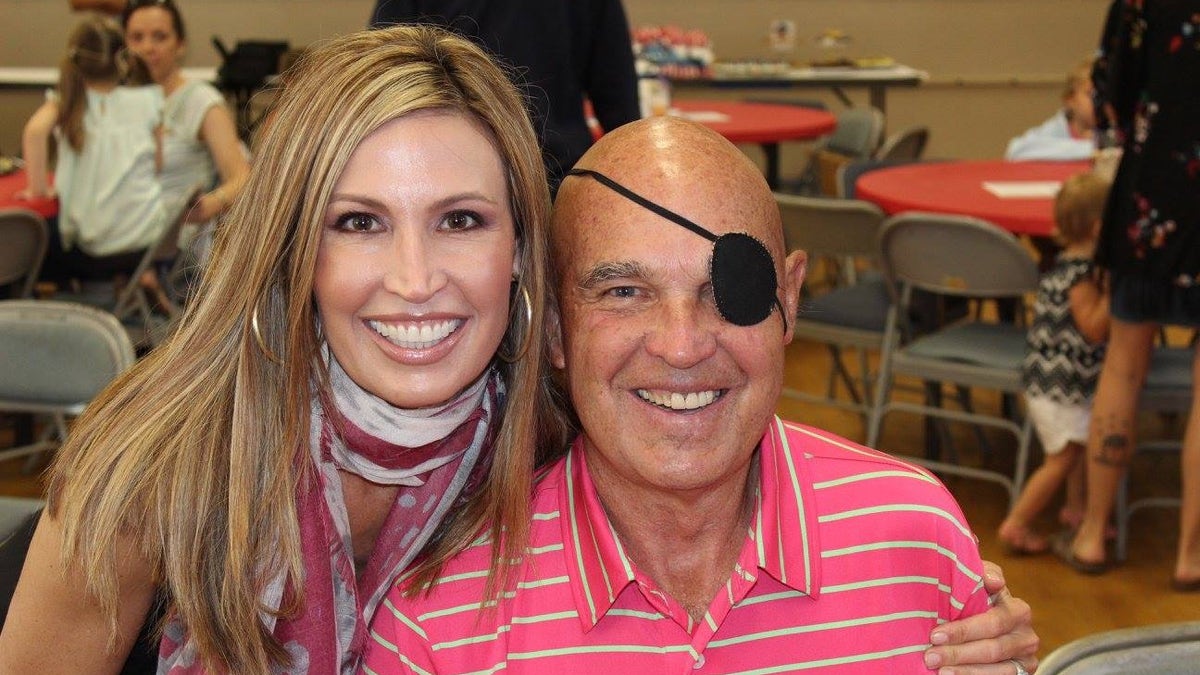

(Courtesy of the author)

Today America commemorates the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the event leading to the birth of our nation, with parades and fireworks displays. But since that world-changing moment of 1776, patriots have sacrificed not just to free the colonies from British oppression, but to see that our nation’s people remain free, and to do what they can to extend those liberties. Sacrifice on behalf of others, in fact, is what comes to mind when I think about the Fourth of July.

My handsome father, Clebe McClary, wears a patch where his left eye used to be, and his left sleeve hangs empty. Only two of his remaining fingers work because of shrapnel fragments embedded in his right hand. Though some might expect him to complain about these injuries sustained in the Vietnam War, I’ve never heard him do so. Instead, Daddy uses his challenges as a platform to encourage people and sums up his war experience this way: “You’ve never lived until you’ve nearly died.”

Daddy walks in gratitude for every day God has given him, and he’s taught me to do the same. He loves our country, and he is proud to have fought for her. From my earliest memories, he has refused to accept that he lost his left arm and eye. “You only lose something when you don’t know where it is,” the argument goes. He feels he gave pieces of his body on Hill 146 in Vietnam, offering them in service to our great nation in hopes of spreading the freedom she represents.

While I was growing up, my parents made it a point to remind my sister Christa and me of the similar sacrifices that red stripe on our flag memorializes. As we stood at attention for the presentation of America’s colors and the singing of the anthem at sporting events, we pressed our right hands over our chests and concentrated on the thump of our little hearts beating against our palms. “Remember,” Mother and Daddy whispered as we settled back into our seats, “there are thousands of soldiers whose hearts no longer beat so that your’s can.”

Those words always brought specific faces to my mind. I’d seen photographs of men like Privates Tom Edward Jennings and Ralph H. Johnson, two men on Daddy’s last patrol whose names are now etched in the black marble of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC. Ralph, a brave eighteen-year-old African American Marine, jumped on a grenade—blowing himself in half—to protect Daddy and the other warrior brothers he loved. Daddy was influential in having the VA hospital in Ralph’s hometown of Charleston, SC, named for him, and he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor posthumously. Later this year, a destroyer will bear his name.

Not long ago I asked Daddy to share about how he and his men could fight so valiantly and selflessly in a war that many Americans opposed. “Freedom comes at a high price,” he said with conviction, “but it is worth fighting for.” And then he went on to explain how the North Vietnamese army of the 1960s used tactics not unlike those employed by ISIS today. To spread their Communist ideology, they tortured and terrorized. Villages were leveled. Civilians who tried to hide in tunnels were smoked out and shot. Women were raped while their husbands watched. Nine thousand people in the city of Hue alone were massacred. One day while out on patrol, Daddy walked into a village where children had missing hands. The enemy had severely maimed those innocents to prevent them from being educated. And Daddy, and his men, were in a position to do something about it.

Of all the honors Daddy has received over the years, one of the most meaningful is a plaque presented to him by the surviving members of his platoon. It reads, “In this world of give and take, there are not enough people willing to give what it takes.”

I’m extremely proud to be the daughter of a patriot who, like so many others throughout our nation’s history, was willing to sacrifice in the hope that freedom and liberty would shine in this world and spread like fireworks across the night sky.