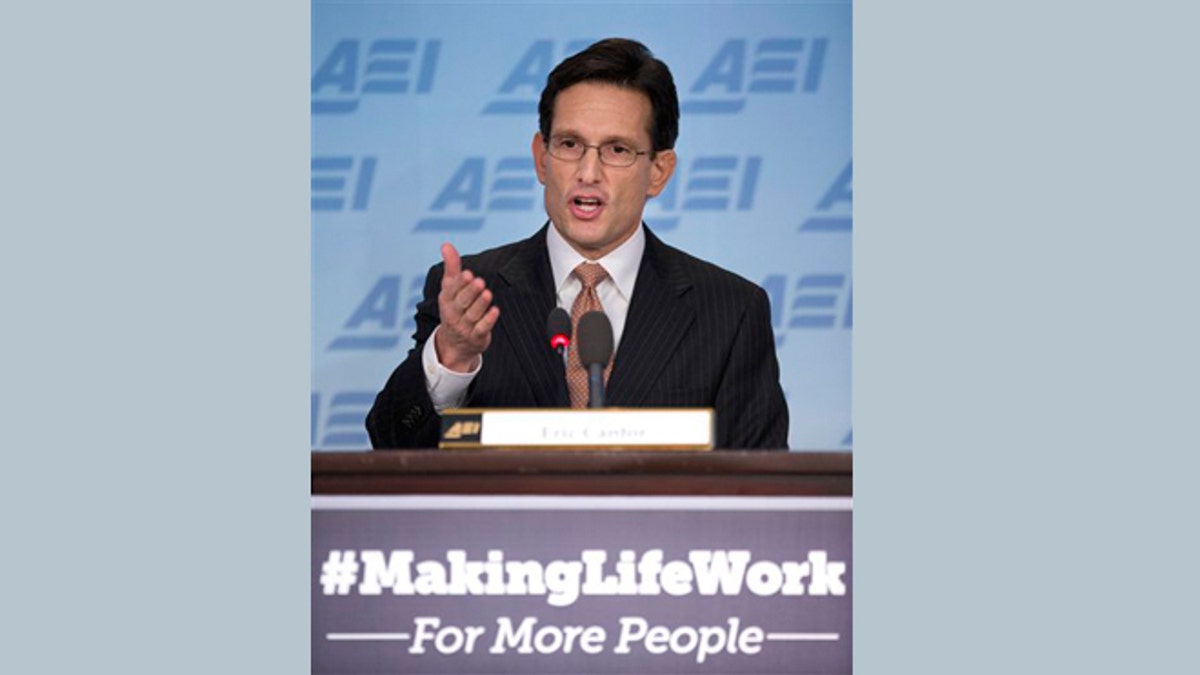

Feb. 5, 2013: House Majority Leader Eric Cantor of Va. gestures as he gives a major policy address entitled: "Making Life Work." at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in Washington. ((AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta))

The liberal-leaning media didn’t think too much of House Majority Leader Eric Cantor’s February 5 speech to the American Enterprise Institute. Yet one particular idea that Cantor mentioned--expanding medical research and cures as a way of reducing the upward pressure of healthcare costs--is full of vast implications for not only the medical health of the American people, but also the political well-being of the Republican Party, still seeking to recover from the wounds of the 2012 election.

Not surprisingly, the mainstream media barely mentioned Cantor’s medical-research point. The Daily Beast surveyed the speech--which also included other significant topics, such as school choice and immigration reform--and minimized its importance; the reporter declared that it consisted of “mini-initiatives,” adding, “Cantor sounds like he is playing small ball.”

Some journalists resorted to outright snark; a columnist for The Washington Post headlined his piece “Eric Cantor’s empty happy talk,” and remarked, “In recent weeks, Republican leaders such as Cantor have resembled nothing so much as laundry detergent salesmen.”

[pullquote]

Okay, now if we cut through the critical spin, what exactly did Cantor say about health care that was so important? Here’s the key line, which doesn’t seem to have been picked up anywhere in the MSM:

“Long term, controlling health care costs will require smarter federal investments in medical research. Many of today’s cures and life saving treatments are a result of an initial federal investment. And much of it is spent on cancer research and other grave illnesses.”

This idea of Cantor’s--that medical research and cures are the key to controlling future health care costs--is worth dwelling on. After all, for the last three years, the Republican message on health care has been dominated by the long-term fiscal plans put forth by House Budget Committee chair Paul Ryan--plans that critics say would make huge and untenable cuts in Medicare and other health programs.

Of course, we’ll never know about those cuts, because they’ve been blocked by the Democrats in the Senate and, ultimately, in the White House. So Cantor and others have come to realize that while Ryan-type budgeting might be the right thing to do, another strategy needs to be tried as well.

In other words, we can see a shift--from what might be called a “Cut Strategy,” to what we can call a “Cure Strategy.” That’s the new idea that Cantor touched upon: It’s better to cure a disease than merely to care for its ravages. Care, to be sure, is always an ethical imperative, but as costs start to mount--Alzheimer’s imposes a $200 billion cost on the economy today, headed toward a cumulative cost of $20 trillion by mid-century--then it’s smart to look for new approaches to curing disease. It’s less expensive to beat than to treat.

But can this be done? Can we achieve such cost-saving medical miracles? Well, we’ve done it before.

Let’s take an example: polio. In 1939, estimates of the number of polio victims -- most of them shut up in their homes, outside of the productive mainstream of American life–ranged from 100,000 to 500,000. As historian David Oshinsky reports, at that time “the expense of boarding a polio patient (about $900 a year) actually exceeded the average annual wage ($875).” In other words, all humanitarian considerations aside, the financial cost of polio was enormous.

In the midst of the ongoing tragedy of polio, Dr. Jonas Salk, working for the March of Dimes, a private charity supported by the federal government, produced a safe and effective polio vaccine in 1955. Was the Salk vaccine a lot of effort? Sure it was. But it was also a social and financial windfall for the United States. As the 20th century medical philanthropist Mary Lasker observed, if you think the health care system is expensive, consider the expense of not having a health care system.

Indeed, financier-turned-health-care-visionary Michael Milken, looking back to the 1950s, has quantified the gains from the vaccine. As he explained in 2010, the costs of immunization programs turned out to be minimal compared to the costs of wheelchairs, iron lungs, and physical therapy:

“In the early 1950s, economists estimated that by the year 2000, treating polio would cost the United States $100 billion annually. Today’s polio immunization programs cost one thousand times less than that and have virtually eliminated the disease.”

In other words, savings from the vaccine were a thousand-fold, an astounding economic achievement. And adjusted for inflation, that $100 billion in 1950 dollars would be more like $1 trillion dollars today. But of course, instead, we are spending virtually nothing on polio in the US--because we don’t have to.

In recent years, others have sought to update the Salk vaccine idea. In May 2011, Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.) was asked by Fox News’ Chris Wallace what might be done about rising Medicare costs. Bachmann, a staunch constitutional conservative, had just voted for the Ryan budget plan, but she told Wallace that she had some additional ideas for saving money on health care:

“The other thing that we should focus on would be cures--cures for things like Alzheimer's, cures for things like diabetes. It’s very expensive to just cover the care for sickness. I'd prefer to see money that we have at the federal level go for cures.”

Once again, a cure is cheaper than care.

Indeed, there’s even some bipartisan momentum for a new approach. Rep. Rob Andrews, Democrat of New Jersey, voted for the Affordable Care Act, aka “ObamaCare,” in 2010, but he has reached the same basic conclusion as Cantor and Bachmann. In a Wall Street Journal editorial published last fall, Andrews called for an “Apollo Program against disease,” recalling the successful moon-landing program of the 1960s. We can thus see, once again, the importance of goals--and the goal, in this instance, is cures. As Andrews wrote, “We are at our best when we focus on great purposes that transform society and transcend politics.” Out of such a large spirit, it’s possible to see constructive common ground.

And now Cantor, the second-highest Republican in the House, has added his powerful voice. Describing the life of a young child from his Richmond congressional district and her successful fight against pediatric cancer, Cantor declared:

“There is an appropriate and necessary role for the federal government to ensure funding for basic medical research. Doing all we can to facilitate medical breakthroughs for people like Katie should be a priority. We can and must do better.”

And so, Cantor said, we must focus anew on medical progress. And yet at the same time, he noted, money is not the only issue; yes, we need to pull together financial resources, public and private, but we need also to clear away legal and regulatory obstacles to scientific advance:

“This includes cutting unnecessary red tape in order to speed up the availability of life saving drugs and treatments and reprioritizing existing federal research spending. Funds currently spent by the government on social science – including on politics of all things – would be better spent helping find cures to diseases.”

Indeed, we might also observe that the continuing revolutions of knowledge -- embodied in Moore’s Law, the World Wide Web, Big Data, and the “Fourth Paradigm” of medical research -- make this a golden moment for medical breakthroughs; the traditional bench science of white coats and laboratory mice can be now be teamed together with data-crunching supercomputers.

So it seems indeed that the wheel of health care policy is turning, slowly, from the Cut Strategy to a Cure Strategy.

The old policy idea, as we have seen, which dominated Washington, D.C. for more than two decades, argued that the main goal should be to cut health care spending, or at least to cut the growth of spending. Republicans, of course, have long sought to curb entitlements such as Medicare, although without success and at great political cost.

For their part, Democrats have supported the expansion of national health insurance programs, but, at the same time, they have argued that their overhaul of the health care system would save money.

In 2008, for example, President Obama pledged to cut health care costs for the average family by a third, or $2,500. Yet that hasn’t happened; over the last four years, health care costs have continued to rise. And of course, costs have risen -- because nothing has been cured, people continue to get sick, and sick people are expensive.

Indeed, over the last few years, new generations of “superbugs” have come to haunt hospitals; meanwhile, production of new antibiotics has plummeted. That problem, right there, is an important health issue--and should be an important political issue.

The new idea, the Cure Strategy, is that the main goal should be to improve health. We must remind policymakers that healthier people are not only happier and more productive, but also that they cost far less. Yes, prevention, diet, and exercise are all important, but many diseases can strike down even the healthiest. It was Alzheimer’s, for example, that struck down the once-robust Ronald Reagan.

Indeed, if Alzheimer’s could be cured, or even alleviated, it might be possible to explore raising the retirement age for Medicare and Social Security; more people working longer would solve the long-term fiscal crisis almost painlessly. With a Cure Strategy in place, we could grow our way to better health and to a more vibrant economy.

The Cut Strategy holds that health care is simply a cost to be curbed; the Cure Strategy emphasizes that good health is the goal--and good health is an asset to be prized. Which idea makes for better politics? More to the point, which idea is better for America?