(AP Photo/J. David Ake, File)

Stories of Washington’s political dysfunction are legion, the laments predictably consistent. Tribalism is rising. The middle has disappeared. The media crave conflict. Voters tune out. Such sad and overwrought tales make for great copy. They reflect what we feel and they’re often true.

Yet below the surface of the grinding gridlock a lot of bipartisan legislating still gets done. The best analogy may come from the world of science, of all places. In quantum physics, things that operate one way in the observable world behave quite differently at the sub-atomic level. In Washington, those who only see the “Newtonian” politics of Twitter and cable TV – of senseless shutdowns and partisan paralysis – are missing an important alternative reality.

Welcome to the world of quantum politics.

The first law of quantum politics is the underappreciated truth that most elected officials came to Washington to get things done. Well-intentioned local leaders from business or state government, these citizen-politicians are accustomed to compromise and eager to make progress. They are serving for the right reasons and lament the nastiness and stalemates.

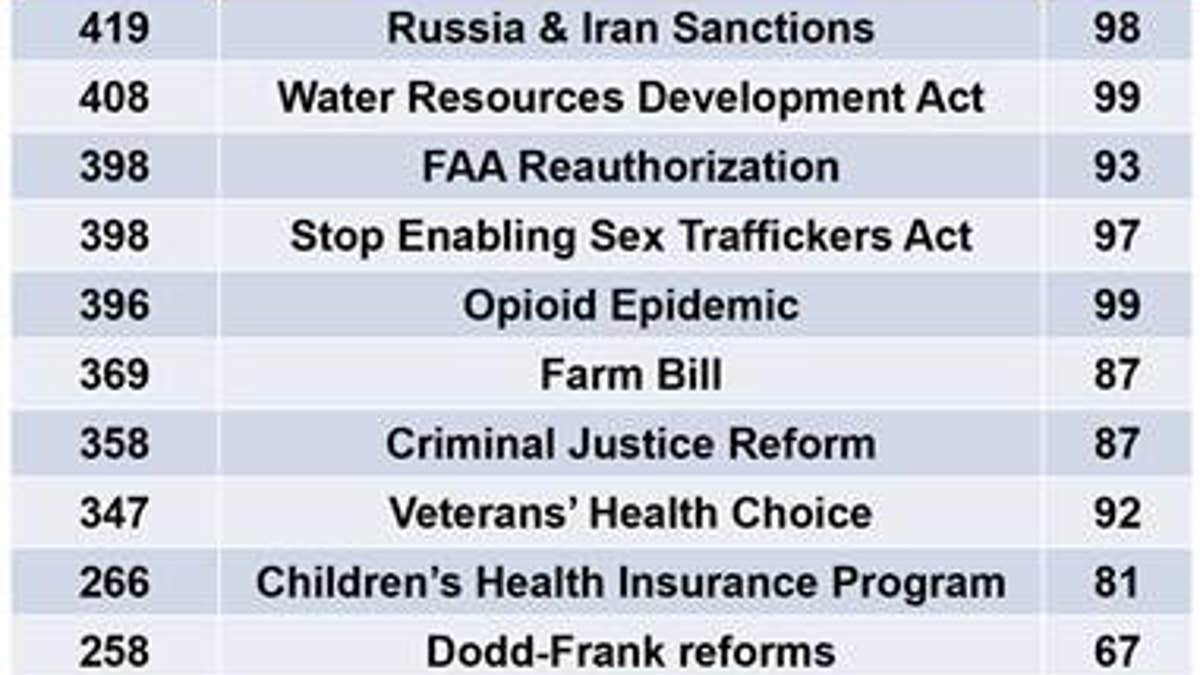

For those able to observe this quantum state, important things are happening, even now. Congress passed more laws in the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency (443) than in the first two years under Presidents Obama (385) and Bush (383). Rather than ceremonial post office namings, many new laws were consequential.

For example, the 115th Congress hammered out compromises to deal with sex trafficking on the Internet, opioid abuse, modernizing export and foreign investment controls, criminal justice reform, water and aviation infrastructure, agriculture policy and children’s health insurance, among other challenging issues.

Persistent efforts by dedicated legislators willing to cut deals ensured these bills were built to last, and most passed with significant majorities rather than token bipartisanship.

Of course these myriad accomplishments are regularly overshadowed by the higher-profile reality TV dumpster fire. Something in the larger system – the party rules, the media bubble, the anger-industrial complex of PACs and NGOs – conspires to render the whole of Congress far less than the individual parts. As underappreciated as its successes have been on so many critical issues, its failures are magnified and over-emphasized.

One sad result: Only 11percent of Americans have a great deal of trust in Congress at a time when policy challenges loom larger than ever.

Many question whether the 116th Congress will prove too distracted by politics to legislate, and understandably so. As many as eight senators are likely to run for president, the most since World War II and perhaps ever.

History suggests many senators running for president resist cooperation, both with the other party (then-Sen. Obama voted against raising the debt ceiling, a position he subsequently regretted) and even their own (Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, called his own majority leader a “liar” on the Senate floor while urging a government shutdown to end the Affordable Care Act).

Yet other senators have aimed to burnish deal-maker credentials, sensing the national desire for less partisan politics. Senators John McCain and Hillary Clinton helped drive meaningful legislation in pursuit of such stature.

Likewise, the Democratic-led House will surely spend a significant amount of time on aggressive oversight of the Trump administration, a tried-and-true formula for heightened partisan animus (see Benghazi hearings).

Indeed, many observers assume Democrats will be unable to resist impeachment proceedings. Yet counterintuitively, the two Congresses that pursued impeachment against Presidents Nixon and Clinton actually enacted more laws than the Congresses that preceded or followed them.

No doubt many reforms could improve the process. Both sides have long abused Senate rules, and today we see historically numerous filibusters and historically few amendment votes allowed.

House leadership retains too much control of process and policy, undermining good bipartisan work by committees and preventing votes on issues that a majority seeks to advance. Gerrymandering reform might reduce the partisan intensity of House districts, while election reforms could encourage more people to vote with reduced risk of fraud.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

But significant policy issues need bipartisan cooperation now. We will likely see meaningful action in the 116th Congress in areas ranging from data privacy to infrastructure to drug pricing to new trade deals.

For business and community leaders attempting to work with their government to get things done, quantum politics requires a strategic approach that remains understated while persistently working both sides of the aisle.

There are more lawmakers willing to cooperate to solve problems for their constituents than you think, such as Sens.Rob Portman, R-Ohio, and Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn. Bipartisan progress persists, even if it cannot be seen by the naked eye.