Fox News Flash top headlines for December 1

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

When Joseph Johnson, age 14, fibbed about his age to enlist in the U.S. Army in 1940, he wasn’t thinking about eternity.

He merely envisioned eating three times a day.

After running away from a troubled home, the Memphis youth insisted to a military recruiter he was 18. The boy got lost in the shuffle. Soon, he and a new band of enlistees were loaded into the back of a truck, heading to Fort MacArthur, California, and a grown-up world Joe knew nothing about.

Looking back on those early years, Joe wrote, as recorded in my biography about him titled "A Bright and Blinding Sun": "I made my share of regrettable choices. It took me a while to come around, to wise up. Every one of us needs redemption."

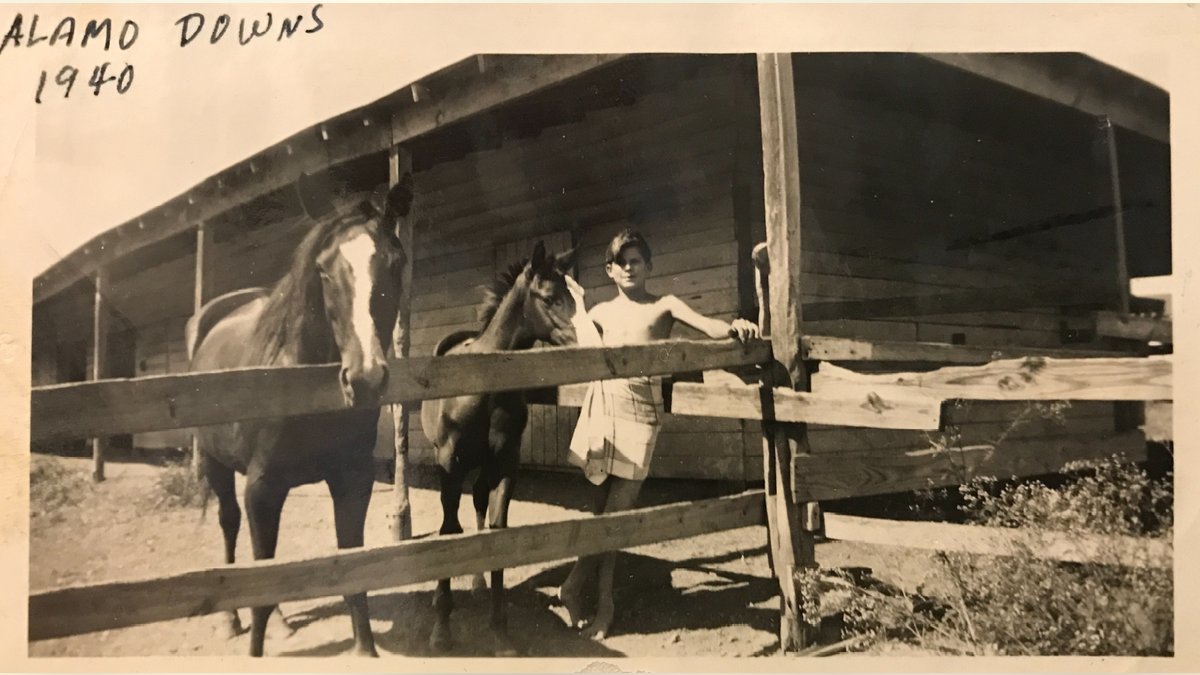

Joe Johnson, age 14, summer 1940, right before he lied about his age and joined the Army.

But in his youth, Joe wasn’t a person of faith. His mom had sent him to a Methodist Sunday school occasionally as a child, but that was it. As a teenage soldier, Joe was sent to the Philippines with the 31st Infantry Division where faith was the last thing on his mind. After war broke out, he served bravely on Bataan and Corregidor until General Jonathan Wainwright’s surrender of all allied forces in the Philippines, May 6, 1942.

Joe was taken prisoner by Imperial Japan and shuffled from one labor camp to another. At a particularly brutal POW camp known as Nichols Field, Joe realized the hard labor, beatings, tropical diseases, and starvation diet had won; he would soon die. Now 16, the boy had grown to over six feet tall, but weighed just 109 pounds.

Joe’s last hope for survival was to be sent to a different labor camp with slightly better conditions. So, he feigned insanity at Nichols Field by running toward a group of guards while slicing his arms with a contraband sharpened spoon. The guards beat him savagely and placed him in an eiso, a boxlike cage smaller than a coffin.

For days, the boy was given no food — and most critically, no water. No one Joe had ever known had survived the eiso. Finally, huddled in the cage, naked, bloodied, desperate, and drifting in and out of consciousness, Joe prayed a simple prayer, "Lord, have mercy." That night a mysterious wind stirred up a cloud, and it began to rain. Joe drank the rainwater that seeped through the slats. Soon, he was sent to the better POW camp.

Veteran Joe Johnson died in 2017.

When World War II ended, Joe came home on a stretcher. He recovered from his physical wounds, yet suffered from severe PTSD. Furious at his former captors, Joe struggled to hold a job and was divorced twice. In middle age, his problems grew so acute that he checked himself into a hospital’s mental health unit. The counselors encouraged him to set down his hate.

Joe, with characteristic grittiness, described his experience: "I was OK after that. Those doctors worked my brain over and straightened my butt out."

Years passed, and as an aged retiree, Joe was flipping through channels on TV and came across the teaching ministry of Atlanta pastor Dr. Charles Stanley. Joe wrote, "Never been much for religion. Most of my life I searched and struggled." But the preacher started making sense to Joe.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR OPINION NEWSLETTER

"Smart fella," Joe added. "Laid things out plain and simple. He was saying how God can spare you from troubles, but God doesn’t always do that. Sometimes you go through the valley of the shadow, yet God walks with you. Only God keeps you going. Well, I knew lots about that valley."

Joe was flipping through channels on TV and came across the teaching ministry of Atlanta pastor Dr. Charles Stanley. Joe wrote, "Never been much for religion. Most of my life I searched and struggled." But the preacher started making sense to Joe.

Right in his living room, Joe bowed his head and made things official. He chose to follow Jesus, believing the biblical truth that God saves people and makes them new.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Joe wrote, "The grace of Christ is deep and wide. After I prayed, I looked back over my last few years and noticed a change had been happening all along. Maybe God had been working in my life, even if I didn’t know it was Him at work."

Joe died in 2017 at age 91 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Those who knew him best said his life had truly changed. His old wounds were gone. His new life had begun.