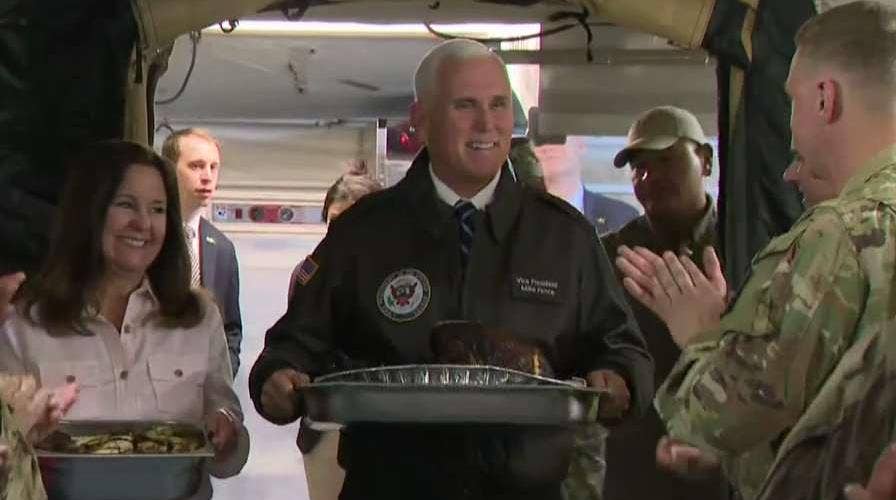

Vice President Pence visits troops in Iraq for surprise trip before Thanksgiving

Pence delivers a Thanksgiving message from President Trump; Lucas Tomlinson reports.

My dad was frugal. He rinsed and reused plates and often asked waitresses for “Just a little hot water and slice of lemon,” then pulled a nasty, used tea bag from his shirt pocket and dropped it in. These behaviors were the result of a deeply held philosophical doctrine articulated to me in my youth with the Yiddishism “A bissel iz a plotz — a little is a lot.”

Mostly this dogma applied to saving money — in fact, it always applied to saving money. My dad grew up a skinny kid on welfare, was 18 when he married my 17-year-old mom, had five children before he was 30 and no safety net if he failed. There was a reason he wasted nothing and reminded us again and again that a little was a lot.

When people ask me what I’ve learned after all these years as a rabbi, one of them is how little things can come between us. A dropped email. A thank you note that never arrived. A little gossip. A little apathy. An unkind word.

NEWT GINGRICH: FIRST THANKSGIVING WASN'T LIKE WHAT YOU WERE TAUGHT IN SCHOOL – HERE'S THE TRUE STORY

Consider the metaphor of the butterfly and chaos theory. According to chaos theory, the things that change the world are often tiny. A butterfly flutters its wings in the Amazonian jungle, and subsequently a storm ravages half of Europe. The butterfly is a symbolic representation of an unknowable quantity — the idea that predictability is impossible because something incredibly small can change everything.

This has made me think about the many small kindnesses and lessons others have bestowed upon me that have changed my life for the better.

When people ask me what I’ve learned after all these years as a rabbi, one of them is how little things can come between us. A dropped email. A thank you note that never arrived. A little gossip. A little apathy. An unkind word.

In his 90’s Lionel told me: “When you travel do it right. Because when you get to be my age you’ll never miss the money and you’ll be glad you have the memories.”

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR OPINION NEWSLETTER

Lionel died this past year but I will never forget him, partly because that little piece of travel advice helped change the son of a guy who reused paper plates and created countless, beautiful memories.

More from Opinion

Max was a suit salesman for 50 years. When we were preparing for his funeral, I asked his daughter Debra, “Well, just how good a suit salesman was your dad?”

“Rabbi,” she said, “one time a woman came in to buy a suit to bury her husband in and my dad sold her two pairs of pants.” I have never forgotten that little lesson about chutzpah and aiming high.

I went to visit Marilyn when she was dying. She looked up at me — gaunt, spent — and said, “Rabbi, I just want to go to dinner and a movie.” To Marilyn … a little was a lot.

I’ve learned a lot in the aftermath of my father’s disease and death; mostly about the power of the seemingly small. It means so much now to remember, to remember everything I can — every lesson, every joke and gesture.

When I sit with a family before a funeral, it’s almost never the person’s resume we end up talking about. It’s the little things — the pancakes your papa made on Sundays. The cage your mom helped build for your pet salamander. The way your dad showed up for you after your divorce. When I visit a hospital room, I see the flower arrangements and cards gratefully propped up on the nightstand. These small gestures pierce the dark isolation of illness; they really matter.

I’ve learned a lot in the aftermath of my father’s disease and death; mostly about the power of the seemingly small. It means so much now to remember, to remember everything I can — every lesson, every joke and gesture. Sundays at the roller rink, watching him and my mother glide and dance on wheels, savoring those few happy, graceful moments. How he worked so hard for so long in the bitter Minnesota cold, and the way he loved butter brickle ice cream on a hot summer night.

My dad’s forgetting disease taught me to remember the greatness of so many tiny, beautiful things. In a world where we all want so much, I learned minimal expectations were best. Toward the end when I visited the nursing home, I was grateful if he was simply awake; the smallest of things.

The last time I arrived in Minneapolis from Los Angeles to visit just for the day it had been months since he had said anything to anyone.

When it was time to say goodbye I looked at him, memorizing his blue eyes in case I never saw him alive again, and simply said, “I love you, Dad.”

He stared back expressionless, pursed his lips again and again and again, then whispered, “And I love you too.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Five words. That turned out to be the last time I saw him alive. Right again, Dad — a little really is a lot.

This Thanksgiving, there will be an empty seat at the table. There will be great gratitude, too, for so many little things that loom so large; little things we can all do more of, especially each whispered, “And I love you too,” fluttering like the wings of a butterfly ...