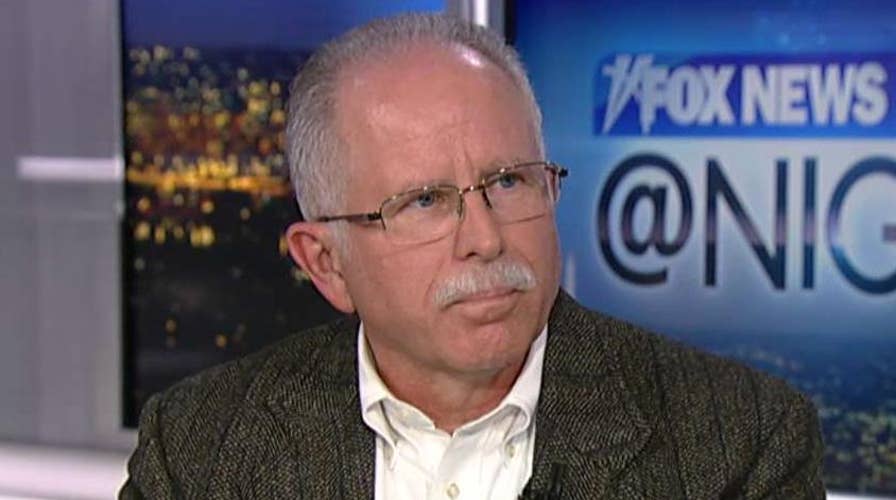

Mark Janus seeks end to mandatory union fees

Janus v. AFSCME could handicap the power of Big Labor.

The American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees lost more than 14,000 members in 2017 – a year after it spent nearly $19 million more on politics than on organizing and advocating on behalf of its members, according to a recent Bloomberg analysis.

Coincidence?

AFSCME is one of the largest contributors to political causes and candidates in the country, but maybe not for long. The U.S. Supreme Court is considering a potentially landmark First Amendment case brought by Mark Janus, a public employee in Illinois who argues that his rights are violated by an Illinois law that forces him to pay for AFSCME’s collective bargaining.

Janus argues that because AFSCME’s collective bargaining with the government affects public policy issues like taxes, spending, pension liabilities and more, such bargaining amounts to lobbying and political speech.

Because the Supreme Court has ruled against compelled political speech, a decision in Janus’s favor could free all public employees in America from being forced to fund government-union collective bargaining against their will.

This should not to be confused with the overt political activity that unions also engage in, such as donations to candidates or parties, or other political spending meant to impact election outcomes. Public employees in all 50 states are already allowed to get back the portion of their dues spent on this kind of politics (although unions make it as difficult as possible).

Making matters worse is that you don’t even have to be a union member to be forced to pay for union advocacy. In the 22 states that don’t have a right-to-work law – including Mark Janus’ home state of Illinois – public employees who opt out of union membership can still be forced to fund union collective bargaining through so-called agency fees.

Not only are agency fees used for collective bargaining that affects public policy, they are also spent on activity that is overtly political in nature, such as donations to politically motivated nonprofit organizations or funding events with a political message.

If the Supreme Court agrees with Janus that agency fees fund political activity and thus should be optional, more than 5 million workers could be freed from paying the fees – and it is likely a significant portion would exercise their right to do so.

In 2015, AFSCME itself estimated that about half of its membership would consider no longer paying dues if they were given the freedom to make that choice. Earlier this year, Politico reported on the National Science Foundation’s General Social Survey findings that 23 percent of unionized government employees don’t believe workers need strong unions.

In 2011, Wisconsin’s Act 10 essentially gave public employees full right-to-work protections as part of broader collective bargaining reforms. AFSCME membership in the state fell by 54 percent in a year.

Clearly, many rank-and-file workers do not agree with or do not find value in AFSCME’s overt political spending, nor its collective bargaining and other activity funded through agency fees.

In a way, this is a compounding problem – as AFSCME expands its political engagement, it pays less attention and resources to actually representing employees at work, causing many to believe the representation is not worth the price.

Moreover, the increased political engagement alienates workers who do not share AFSCME’s political positions, causing them to opt out. Either way, it puts both political dues as well as agency fees at risk.

Regardless, if the Supreme Court ends AFSCME’s forced-dues gravy train this year, the union will face the same challenge as nearly every other organization in America – having to earn every dollar it receives by demonstrating value creation for members.

If that becomes the case, AFSCME will have important decisions to make about where and how it spends its resources, lest it continue to see membership trend downward like it did in 2017.