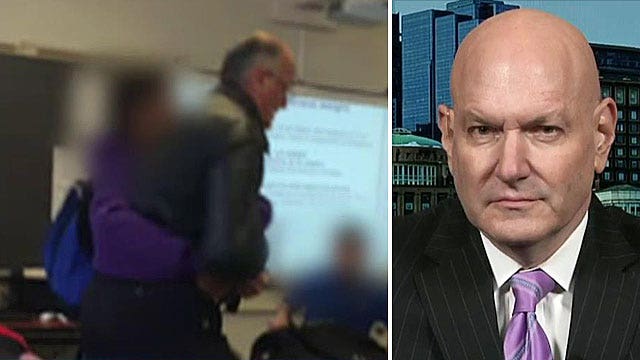

Dr. Ablow on dangers of growing dependence on cell phones

Reaction to student attacking teacher over confiscated phone in N.J.

Last Tuesday, a ninth-grader at John F. Kennedy High School in Paterson, N.J., was caught on video throwing his 62-year-old teacher to the ground and wrestling with him in order to retrieve his cellphone, which the teacher had confiscated. Teachers at the school allow cellphones to be used for educational purposes in the classroom, but they may take them and hold them until the end of class if a student appears to be using his phone for any other purpose.

Granted, the boy may have demonstrated problems controlling his impulses in other settings, too, but the video of his attack has resulted in national attention. And that’s because it isn’t the first dramatic example of how attached to our phones we have become.

Last year, a Houston woman was shot by a mugger when she refused to hand over her cellphone. She survived, and she later asserted that she had done the right thing.

We have already crossed the Rubicon, almost irrevocably incorporating technology into our psyches in a way that makes us part flesh and blood, part hardware.

In 2013, a 22-year-old man was killed by a train when he tried to retrieve the cellphone he had dropped on the tracks.

Without giving a great deal of thought to the psychological implications, our species has deployed mobile technology very quickly, in a very widespread manner. One reason is that the marketplace embraced smartphones in an astounding way — as if our phones and their apps are a lock-and-key fit with our psyches. According to one source, there are 7 billion mobile devices on earth, one for almost each person.

What is “in” our cellphones that would lead people to attack others or risk death to keep them? I would argue that the phones absorb and record our thoughts and intentions so dramatically that we become unconsciously convinced they are “parts of us.” Why else would so many people hesitate even to leave a room without taking their cellphones with them? Why would they interrupt meetings and family time to check them? Why would young people be opting to spend their money on newer, faster ones, instead of on clothing?

Why would there be so much interest in personalizing the sounds they make, the apps they hold and the cases that hold them?

I contend we have already crossed the Rubicon, almost irrevocably incorporating technology into our psyches in a way that makes us part flesh and blood, part hardware. The fact that the hardware is outside our bodies (for now) does not mean the integration has not occurred. We are psychologically magnetized to our devices. That’s why some people will fight for them, and even die for them.

The selfie has become so ubiquitous that it no longer seems bizarre to see someone smiling into a cellphone or sticking out her tongue or making a sad face — acting — and then snapping a photo. And these images are then sent not only to her supposed “friends,” who may number in the hundreds, but also to her unconscious mind — reinforcing the idea that she is what her cellphone records her to be. Take away the cellphone and, in some measure, she believes she disappears. She feels she dies a little bit, or more than a little bit, psychologically.

The business of selling “selfie sticks” — telescoping rods that hold a cellphone far enough away to facilitate a really good shot — is robust enough to make many retailers place large kiosks of them near the checkout register. Cellphones, you might say, are growing arms. Ours apparently aren’t long enough.

This is just the beginning. Cellphones will soon be able to determine whether you are looking at the content on their screens, rather than looking away. They will demand attention. The extent to which we own them versus them owning us will be increasingly in doubt.

Make no mistake: While technology can be good when harnessed for the good (raising money for charity occurs to me), there will be hell to pay for giving so little thought to the downside. That downside likely includes an epidemic of narcissism in young people, increased rates of anxiety and dramatically decreased feelings of autonomy. Because to the extent that one’s self-image is outsourced to a mobile device, it is no more deeply rooted than that.