Scalise opens up on return to Congressional Baseball Game

One year after he was shot on the practice field, the House majority whip speaks out on the attack and his recovery on 'Fox & Friends.'

Ten more minutes. I’d be ready to leave in 10 minutes. It was like being a kid out on the sandlot. Then a world-shattering tragedy: Mom calling out that dinner’s ready. Ten more minutes, Mom! Fifteen, tops! I had a reason for staying as long as I could: This was the last practice. The game was tomorrow. My family was coming up, and the game was at Nationals Park, the new 41, 000-seat stadium. Sure, we wouldn’t exactly be packing the stands, but we’d have a few thousand people there and, most importantly, my wife and kids wearing their GEAUX SCALISE shirts. There was a little added pressure this year, too.

The score between Democrats and Republicans, going back to the first game in 1909, was tied. Republicans had won 39 times. Democrats had won 39 times. This was our chance to pull ahead in the series. Not to mention I knew Cedric Richmond, one of my best friends in Congress and the star player for the Democrats, was going to be at the top of his game. I couldn’t let him have another win. I needed to be ready. I needed to squeeze as much out of the last practice as I could. By then it had turned into a bright, clear day, and I decided a few more minutes wouldn’t throw my schedule off too much.

I take practice seriously. I attend every single one. I have fun on the field, but in my mind, I’m at the game. When I take my turn at batting practice, I’m pretending the batting practice pitcher is Cedric. I’m making him work the strike zone. I’ll let a dozen balls zing past without swinging if I don’t think they’re strikes, while the other players roll their eyes. “Swing or give someone else a chance, Scalise!” I’m not a power guy, I’m not hitting home runs; I’m all about getting on base, singles and doubles and drawing walks, so a good eye for balls and strikes is key. Batting practice for me is as much about honing my eye for the strike zone as it is actually hitting the ball. And when I’m out in the field, I’m scooping every grounder like the Democrats are about to score the winning run. So that’s what I was doing at that practice, just sitting there in position at second base, thinking of excuses to stay longer, like I was in high school, just like the pick-up football and basketball and softball games after the last bell rang at Archbishop Rummel High, me and the guys squeezing as much fun out of the day before the sun goes down.

I was in the zone. We were in the zone. We’d been playing well. We were almost ready. I should have left to get ready for the day, go over my remarks for the red snapper announcement, and prepare for my other meetings, but I felt too good. I knew the red snapper talking points backward and forward, so why not stay out a little longer? The sun felt good. The sound of bats hitting leather was like music. My arm felt good, tensile, and I’ll grant you, the throw from second to first isn’t a country mile, but I felt I could fire that thing over the Potomac if I needed to. I had that coiled energy. It was just a good day, a good practice, and as Congressman Duncan walked off the field and fist bumped me, I thought, Yeah, we’re ready; we’re loose, but we’re focused.

All the grounders are coming to middle infield, and I am scooping them up and firing them over to first base without bobbling even one of them, just hoovering them up, firing them over, running and scooping and firing, one after the other. I am in my rhythm, in the zone, scooping and throwing, scooping and throwing, my body feeling good, my 51-year-old frame feeling lithe and elastic. Suddenly I notice how the last hint of that faint morning chill has cooked off to make way for a pure, early summer heat, and then there is a bang. I think, That’s okay; it’s nothing. I’m still standing there in the sun thinking about strategy and Cedric’s fastball and my family and my son’s first U2 concert and a tractor -- I see a tractor and the noise makes sense, except there’s no one on the tractor. There’s another noise, and I can’t force it out anymore; I have to allow this new reality to press itself in on me, that someone is shooting. It’s strange though; gunfire and baseball don’t fit together, and it’s also strange that there’s a kind of numbness around my waist. A kind of pressure, like a lineman has lowered his shoulder and given me a shove. But it’s not a shove. It’s a large 7.62 caliber bullet moving at high velocity that has entered my hip and hit my femur, and my leg has effectively detonated. The bones explode. My femur explodes, my pelvis explodes; a puff of bone and metal fragments fly through my pelvis and abdominal cavity, turning my body into a shrapnel-packed bomb going off in a confined space. The support structure that keeps the whole architecture of my body upright is now a broken-apart puzzle, and there’s no exit wound, so there’s nowhere for all that energy to go.

Hard things ricochet around like pinballs, severing veins and slicing open organs, shredding through my intestines and destroying my digestive tract, rattling nerves, making everything bleed all at once. But all the damage is internal. Except for one almost imperceptibly small hole in my baseball pants, it’s invisible from the outside. I’m trying to move on pulverized leg bones. I feel like someone else is controlling my legs. My legs stop working. It’s not pain exactly, and I don’t know that the reason I’m falling is because my whole foundation has imploded. I feel instead like the wiring that connects my brain to my legs has been unplugged. I fall.

Now I’m on my hands in the dirt, facing the outfield. I don’t know why I’m facing the outfield, when I was just facing the other way. I don’t know that the force with which the bullet hit me has spun me almost all the way around. Things I don’t know are replaced by things I do know. The shooting hasn’t stopped; I know that. I can hear more and more gunfire. I know that to survive I have to run away from it. I know I can’t run away from it because I can’t move my legs. I have to crawl. Somehow I know that the gunman is behind me. Something tells me that. Some invisible system in my body has run a kind of algebra, an algorithm that’s taken information in, run the numbers, and calculated, without me even being conscious of it that because my body spun to where it is, and because the bullet entered where it did, the bullet must have come from the infield. So now I’m moving away from the infield as fast as I can. Which is not very fast at all. One arm after the other, barely making progress. Bullets cracking overhead. An army crawl, but without legs. I’m trying to swim on dry land. I dig my palms into the dirt so hard that pebbles implant in my palms, almost totally buried in the skin. I pull, and pull, and pull. I claw at that dense, red clay. I move inches at a time.

Safety seems impossibly far away, unreachable. More bullets zing above me. I pull for 10 minutes but it feels like a half hour, an hour. I know I’m going to lose my arms soon, just like I lost my legs. The ground becomes softer. I’ve reached the grass. I somehow notice, despite everything going on, that the grass is still damp with dew. It feels like a year ago that I lost my legs. It’s starting to happen again with my arms, a fuzzy cellphone connection that I’m losing, my conversation partner disappearing into a tunnel. I need to keep moving away from the shots before I lose control of my arms. But each pull becomes harder and harder. There’s a word for what’s happening to me: exsanguination. My body is emptying itself of blood. I’m bleeding so much that I will die. I’m painting the field with a two- foot- wide brush stroke of blood, but mixed in with the grass it doesn’t look so much like blood. It’s not really red but brown, like the grass decided to die as I moved past. The gunfire hasn’t stopped. Someone is still coming after me.

But strangely, it isn’t fear that’s overtaking me. It’s just a very clear goal. I have to get away from the gunfire. I’m inching away from it, and at any moment, whoever’s shooting might walk up to me, casual as you like, and execute me on the ground. I feel like all that’s stopping him is that I’m escaping. At an excruciatingly slow pace. Then it happens. I lose control of my arms. I can’t move them, I can’t make them do anything at all, and I know what I need to do.

With my face in the dirt, grass and dew filling my nostrils, I begin to pray. And as I do, I see clearly big church doors opening, and I see, framed there like an angel, a young woman. I feel I recognize her. I know her. She’s mine. It’s my daughter, Madison; it’s the grown-up version of my 10-year- old daughter, 15 or 20 years in the future, standing in a wedding dress, framed by those big doors. She’s alone. There’s no one next to her. No one’s there to walk her down the aisle, because she has no father. Because I’m not there for her. I feel a twist in my gut, and now I know what I need to pray for. Please God, I pray, don’t let Madison walk down the aisle alone. Please, she’s daddy’s little girl. Let me be there. Please, just let me be there with her. Please God, let me see my family again; let me see Jen and the kids again. The shooting changes. It doesn’t stop. In fact, it seems to increase. But it becomes a different kind of sound. I can tell that it’s coming from somewhere new. A different sound means a different caliber. I know what that means. It means we’re shooting back.

We’re shooting back. The realization comes over me as a relief. Dave and Crystal are shooting back. Please God, protect Dave and Crystal. Let their aim be true. Let them carry out their mission. I realize I feel calm now. That, actually, I’ve felt that way since the moment I started to pray, a powerful sense of calm coming over me. I think of more things to ask for, so I ask for those too.

I’m being a little more demanding than I usually am when I pray -- less a servant of His will and more like a child focusing intently on a Christmas list, but it centers me. I can feel a burden being lifted off of me. I feel a weight disappearing. Like someone is saying, Okay, a bad thing is happening; you’re hit, but I’m just gonna take some of that burden away from you. A calm voice saying, Hang in there, Steve, with a slight Southern twang, We’re gonna get ya. It sounds so real, it can’t just be in my mind, and before I can think, Huh, so God has a Southern twang, I hear it again. I’m watching, Steve. We haven’t forgotten ya. We’re gonna get ya. And I realize, I do recognize that voice. That’s Mike Conaway, our first basemen and the congressman from Texas’s 11th district. When my arms gave out and everything started powering down, my head was turned toward first base, so once I understand I’m hearing Mike’s voice, I understand I can see him over there, too. He’s not too far away. He’s calling to me, comforting me. And I know I’m not alone.

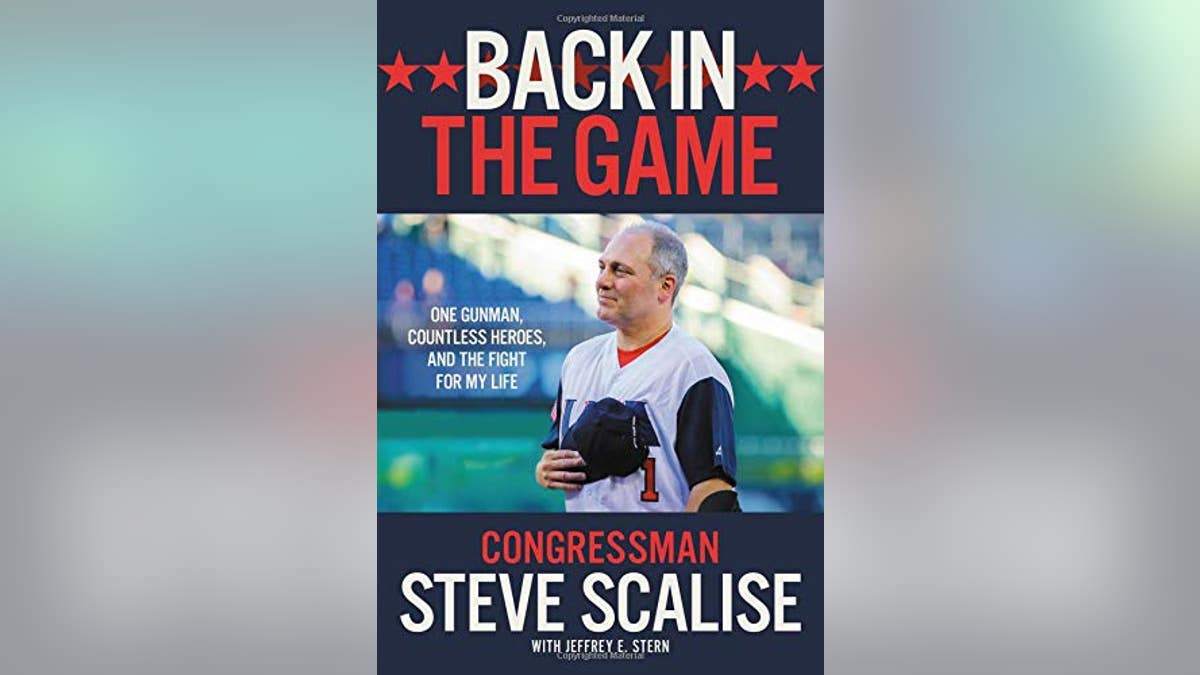

This is an excerpt from House Majority Whip Steve Scalise's new book, "Back in the Game: One Gunman, Countless Heroes, and the Fight for My Life," on sale November 13, 2018.