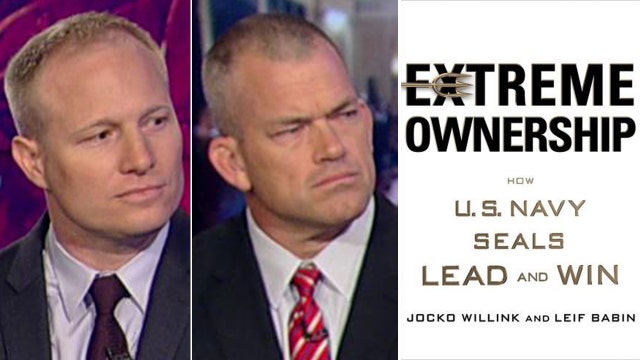

Former Navy SEALs want to see 'Extreme Ownership' in DC

Jocko Willink and Leif Babin discuss their new book on 'America's Newsroom' and how it relates to leadership in Washington

Editor's Note: The following is an excerpt from EXTREME OWNERSHIP: How U.S. Navy SEALs Lead and Win by Jocko Willink and Leif Babin. Copyright © 2015 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin's Press, LLC.

THE MA’LAAB DISTRICT, RAMADI, IRAQ: FOG OF WAR

Our first major operation in Ramadi was total chaos. The operation had kicked off before sunrise, and with the sun now creeping up over the horizon, everyone was shooting.

Both of my SEAL sniper elements had been attacked and were now embroiled in serious gunfights. As the element of Iraqi soldiers, U.S. Army Soldiers, and our SEALs cleared buildings across the sector, they met heavy resistance. As we monitored the radio, we heard the U.S. advisors with one of the Iraqi Army elements in advance of the rest report they were engaged in a fierce firefight and requested the QRF (Quick Reaction Force) for help. Minutes later, over the radio net, one of my SEAL sniper teams called for the “heavy QRF,” which meant my SEALs were in a world of hurt and in need of serious help. I asked the U.S. Army company commander we were with to follow the tanks in.

(Jocko Willink (St. Martin's Press))

Our Humvee rolled to a stop just behind one of the Abrams tanks, its huge main gun pointed directly at a building and ready to engage.

(Leif Babin (St. Martin's Press))

Running over to a Marine ANGLICO gunnery sergeant, I asked him, “What’s going on?”

“Hot damn!” he shouted with excitement. “There’s some muj in that building right there putting up a serious fight!” He pointed to the building across the street. “They killed one of our Iraqi soldiers when we entered the building and wounded a few more. We’ve been hammering them, and I’m working to get some bombs dropped on ’em now.”

The building he pointed to was riddled with bullet holes. Now the Abrams tank had its huge main gun trained on the building, preparing to reduce it to rubble and kill everyone inside. And if that still didn’t do the job, bombs from the sky would be next.

But something didn’t add up. We were extremely close to where one of our SEAL sniper teams was supposed to be. That sniper team had abandoned the location they had originally planned to use and were in the process of relocating to a new building when all the shooting started. These Iraqi soldiers and their U.S. advisors shouldn’t have arrived here for another couple of hours. No other friendly forces were to have entered this sector until we had properly “deconflicted”—determined the exact position of our SEAL sniper team and passed that information to the other friendly units in the operation. But for some reason there were dozens of Iraqi troops and their U.S. Army and Marine combat advisors in the area.

As the SEAL task unit commander, the senior leader on the ground in charge of the mission, I was responsible for everything in Task Unit Bruiser. I had to take complete ownership of what went wrong. That is what a leader does—even if it means getting fired.

“Hold what you got, Gunny. I’m going to check it out,” I said, motioning toward the building on which he had been working to coordinate the airstrike. I nodded at my senior enlisted SEAL, who nodded back, and we approached the door to the compound, which was slightly open. I kicked the door the rest of the way open only to find I was staring at one of my SEAL platoon chiefs.

“What happened?” I asked him.

“Some muj entered the compound. We shot one of them and they attacked—hard-core. They brought it.”

At that moment, it all became clear. In the chaos and confusion, somehow a rogue element of Iraqi soldiers had strayed outside the boundaries to which they had been confined and attempted to enter the building occupied by our SEAL sniper team. In the early morning darkness, our SEAL sniper element had seen the silhouette of a man armed with an AK-47 creep into their compound. Our SEALs had engaged the man with the AK-47, thinking they were under attack. Then all hell broke loose.

When gunfire erupted from the house, the Iraqi soldiers outside the compound returned fire and pulled back behind the cover of the concrete walls across the street and in the surrounding buildings. They called in reinforcements, and U.S. Marines and Army troops responded with a vicious barrage of gunfire into the house they assumed was occupied by enemy fighters. Meanwhile, inside the house our SEALs were pinned down and unable to clearly identify that it was friendlies shooting at them. All they could do was return fire as best they could and keep up the fight to prevent being overrun by what they thought were enemy fighters.

“It was a blue-on-blue,” I said to him. Blue-on-blue—friendly fire, fratricide—the worst thing that could happen.

…

The rest of the mission was a success. But that didn’t matter. I felt sick. One of my men was wounded. An Iraqi soldier was dead and others were wounded. We did it to ourselves, and it happened under my command.

As we debriefed, it was obvious there were some serious mistakes made by many individuals both during the planning phase and on the battlefield during execution. Plans were altered but notifications weren’t sent. The communication plan was ambiguous, and confusion about the specific timing of radio procedures contributed to critical failures. The Iraqi Army had adjusted their plan but had not told us. Timelines were pushed without clarification. Locations of friendly forces had not been reported. The list went on and on.

Within Task Unit Bruiser—my own SEAL troop—similar mistakes had been made. The list of mistakes was substantial. But something was missing. There were so many factors, and I couldn’t figure it out. I looked through my notes again, trying to place the blame.

Then it hit me.

Despite all the failures of individuals, units, and leaders, and despite the myriad mistakes that had been made, there was only one person to blame for everything that had gone wrong on the operation: me. I hadn’t been with our sniper team when they engaged the Iraqi soldier. I hadn’t been controlling the rogue element of Iraqis that entered the compound. But that didn’t matter. As the SEAL task unit commander, the senior leader on the ground in charge of the mission, I was responsible for everything in Task Unit Bruiser. I had to take complete ownership of what went wrong. That is what a leader does—even if it means getting fired.

A few minutes later, I walked into the platoon space where everyone was gathered to debrief. I stood before the group. “Whose fault was this?” I asked to the roomful of teammates.

After a few moments of silence, the SEAL who had mistakenly engaged the Iraqi solider spoke up: “It was my fault. I should have positively identified my target.”

“No,” I responded, “It wasn’t your fault. Whose fault was it?” I asked the group again.

“It was my fault,” said the radioman from the sniper element. “I should have passed our position sooner.”

More of my SEALs were ready to explain what they had done wrong and how it had contributed to the failure. But I had heard enough.

“You know whose fault this is? You know who gets all the blame for this?” The entire group sat there in silence. I took a deep breath and said, “There is only one person to blame for this: me. I am the commander. I am responsible for the entire operation. As the senior man, I am responsible for every action that takes place on the battlefield. There is no one to blame but me. And I will tell you this right now: I will make sure that nothing like this ever happens to us again.”

It was a heavy burden to bear. But it was absolutely true. I was the leader. I was in charge and I was responsible. Thus, I had to take ownership of everything that went wrong. Despite the tremendous blow to my reputation and to my ego, it was the right thing to do—the only thing to do. I apologized to the wounded SEAL, explaining that it was my fault he was wounded and that we were all lucky he wasn’t dead. We then proceeded to go through the entire operation, piece by piece, identifying everything that happened and what we could do going forward to prevent it from happening again.

Looking back, it is clear that, despite what happened, the full ownership I took of the situation actually increased the trust my commanding officer and master chief had in me. If I had tried to pass the blame on to others, I suspect I would have been fired— deservedly so. The SEALs in the troop, who did not expect me to take the blame, respected the fact that I had taken full responsibility for everything that had happened. They knew it was a dynamic situation caused by a multitude of factors, but I owned them all.

That is Extreme Ownership, the fundamental core of what constitutes an effective leader in the SEAL Teams or in any leadership endeavor.