(AP Photo/Terry Spencer)

Invited by President Trump to participate in the service for the National Day of Prayer last week, Rabbi Yisroel Goldstein, the congregational leader who was among the wounded in the Poway synagogue shooting that left a worshipper dead, was expected to recount his ordeal, which he did. He also warmly thanked the president for the phone call he received from him after the shooting.

But then the rabbi did something else. He advocated the adoption of the much-maligned “moment of silence” for all the nation’s public schools.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1962 that official organization, sponsorship, or endorsement of school prayer is forbidden by the First Amendment, “moments of silence,” allowing children to use the quiet time however they choose, have been found to not run afoul of the Constitution, as long as praying is not overtly encouraged. More than 30 states have provisions that either mandate or allow for a moment of silence in the classroom at the beginning of every day.

For those who cower in fear of imaginary cracks in the church-state wall, such silence isn’t golden, but rather a tip-toeing back-door encroachment on freedom of religion – or, more descriptively, freedom from religion, which they see as the American ideal.

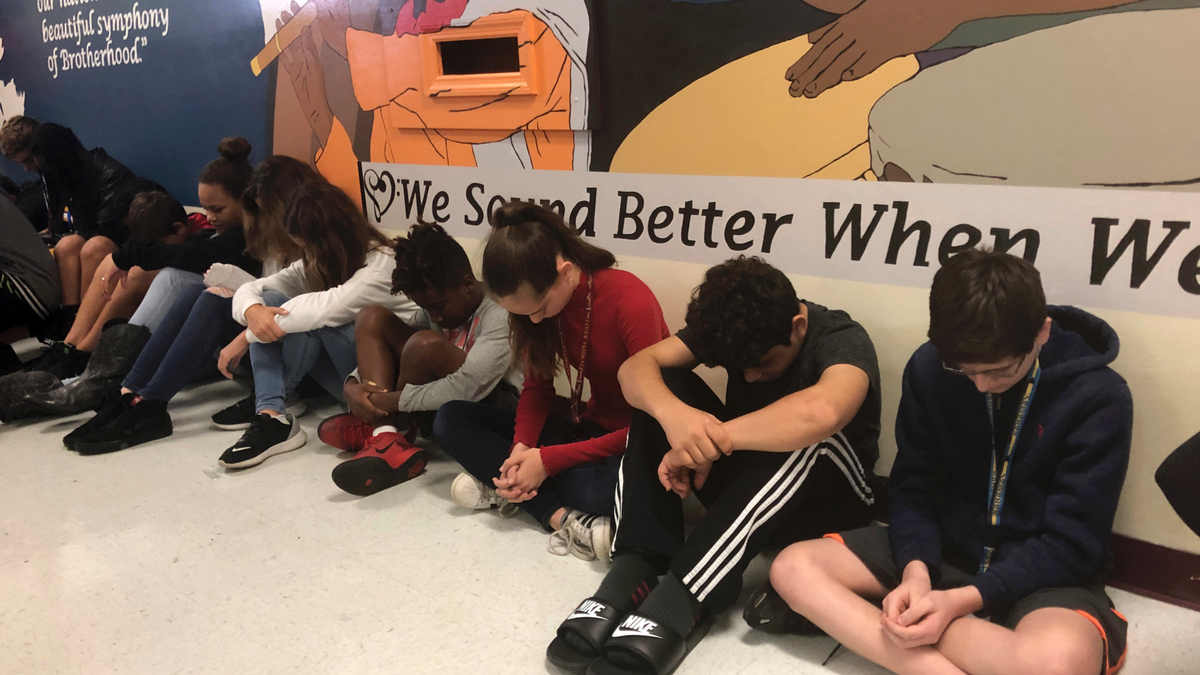

For the less panic-prone among us, promoting more widespread school-day moments of silence is an alluring proposition. With young people’s developing minds more overwhelmed than ever these days – battered by nearly nonstop advertising, social media interactions, text messages and streaming entertainment, all competing for their attention – an enforced sixty seconds (or, perhaps better, a few hundred ones) would provide minor citizens with something invaluable and increasingly rare: an opportunity to just think.

That’s surely a worthy goal in itself.

But would starting a school day with a moment of silence have any effect, as Rabbi Goldstein seemed to imply, on hatred and societal violence?

Children harboring even latent viruses of anti-Semitism, racism, radical Islamism or a nondenominational desire to gleefully murder innocents, after all, could conceivably just use their quiet time to fantasize about and nurture their inner evil.

And even kids who aren’t violently inclined might simply seize the literal moment to plan a prank on a fellow student or a teacher, mentally replay last night’s television show or, if the show kept them up too late, just doze off. Especially when the moment of silence is presented as nothing more than what the phrase literally means.

So, in light of the anodyne nature of constitutionally permitted moments of silence, a cynic might reasonably maintain that there is nothing to be gained by promoting them.

But the cynic would be wrong. Because there is a third path here, and it could well lead to a more mentally healthy and responsible citizenry.

What, to wit, if moments of silence were instituted in all the nation’s schools and described neither as a time for focusing on God nor mere downtime for meaningless mental meanderings?

I’m not a lawyer – I don’t even pretend I’m one on Facebook. But I think it should be constitutionally kosher (please excuse the word) were moments of silence presented to kids, particularly high schoolers, clearly and shamelessly as a time to reflect on the significance of their lives?

Wondering whether we have a meaningful role to play in this world may strike some as a religious endeavor. But it really isn’t, or at least needn’t be. It’s a human one.

To be sure, as a religious person, I’ve always believed that, without accountability to Something Higher, there can be no more meaning to good and bad behavior than to good or bad weather; no more import to right and wrong than to right and left. But atheists with whom I have interacted vehemently insist that they see their lives as significant even without God in the picture, and that they feel charged – self-charged, I suppose – to act in a moral and ethical manner.

Well, if so, then there should be just as much for an atheist to ponder in a moment of silence as there is for a rabbi, priest or imam. And so it follows that no atheist should have an objection to public school teachers daily directing their charges to give some thought to how they should live their lives.

First Amendment problem solved. Whether the problem of societal violence in America can be solved, though, and whether moments of silence in schools can be part of the solution, isn’t known.

But it certainly strikes me as worth a try.