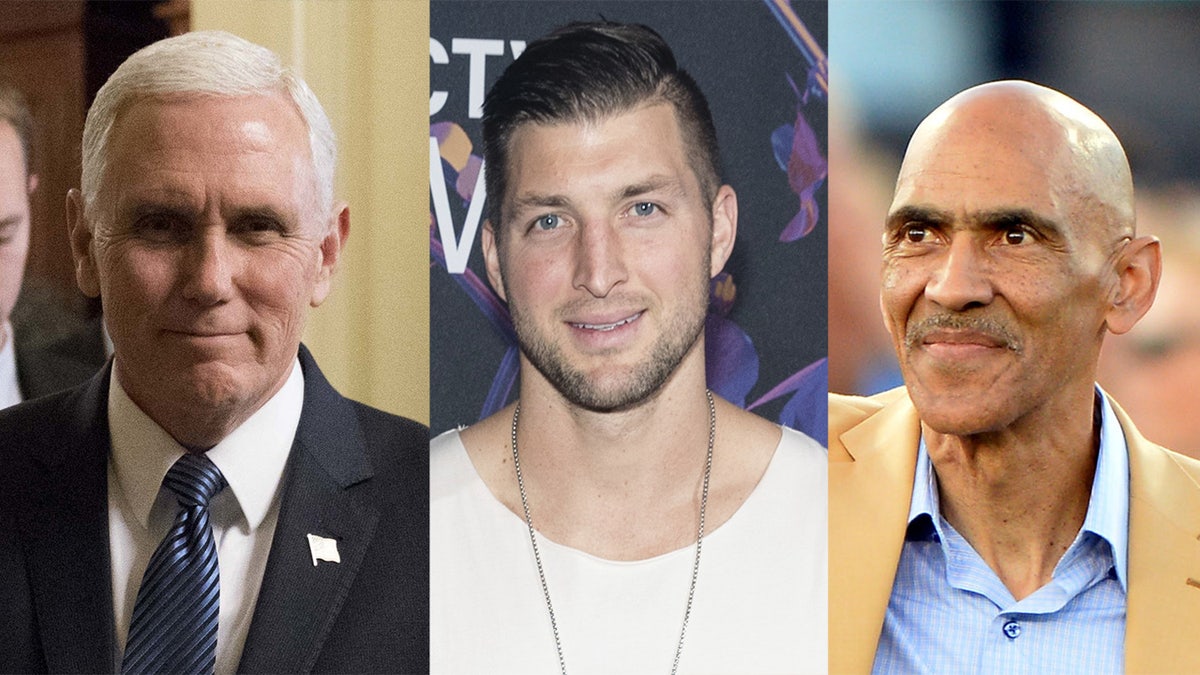

ABC News, Joy Behar slammed for Mike Pence joke

Joy Behar, “The View” co-host, is raising eyebrows for mocking Vice President Mike Pence’s Christian faith and comparing it to mental illness. Pence himself fired back at the comedian and ABC News saying the comment “is just wrong.”

Is believing in God a sign of mental illness? Is praying a silly exercise in make-believe – just a big waste of time and a delusional activity?

I certainly don’t think so, nor do most Americans. But on Tuesday, panelists on “The View” on ABC TV mocked Vice President Mike Pence for his Christian faith, calling it “scary” and even saying that his religious beliefs are a kind of “mental illness.”

Such comments are an insult to everyone who holds sincere religious beliefs.

The vice president – a deeply religious man – responded Wednesday to the attack, saying at an event sponsored by Axios: “It’s just simply wrong for ABC to have a television program that expresses that kind of religious intolerance.” Pence added that criticism of anyone who is religiously observant shows how “out of touch some in the mainstream media are.”

Pence is right. No matter what you think of his politics, his views on public policy issues, or his performance in elective office, he should not be criticized for his Christian beliefs.

The pile-on started when “The View” played a segment of “Celebrity Big Brother,” in which former White House staffer Omarosa Manigault Newman said that Americans should be worried about Pence because he thinks Jesus speaks to him.

In response to the video segment, panelist Sunny Hostin questioned the sincerity of Pence’s religious beliefs, while panelist Joy Behar suggested that Pence might have a mental illness.

“It’s one thing to talk to Jesus,” Behar said. “It’s another thing when Jesus talks to you.”

Media outlets and social media critics immediately piled on Pence, with many of them putting the worst possible spin on Pence’s faith and prayer life.

What the media and critics haven’t done, and won’t do, is to point out that their attacks on Pence are part of a larger and very disturbing trend in American life – an ugly form of prejudice called Christian shaming.

We experienced Christian shaming recently when NBC sports commentator Tony Dungy came under fire for commending Super Bowl MVP Nick Foles of the victorious Philadelphia Eagles on his faith before the game and for calling Foles’ faith a significant factor in his confidence and performance against the New England Patriots.

Dungy’s remarks were met with a wave of social media outrage.

The first response was a critic who tweeted, “unbelievable you would use your employer, @NBCSports, to spout this nonsense on the air.”

Another early critic tweeted, “Does NBC want you preaching on air?”

We also experienced this sort of Christian shaming when social media flash mobs mocked evangelicals who had called on our nation to pray in the aftermath of terrible shootings (like the one in Parkland, Florida on Wednesday), natural disasters and other harrowing events that have unfolded in recent years.

In the view of these Twitter activists, a Christian’s tweets about prayer are simply a means of avoiding the issue instead of acting upon it.

Similarly, former NFL player Tim Tebow was often criticized and mocked for openly kneeling in prayer and expressing his Christian faith. He wore Bible verses on his eye black in college. He was not embarrassed to be a Christian – he was proud to proclaim his belief in Christ.

Christians were also on the receiving end of public shaming from the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights. In a 2016 report on religious liberty titled “Peaceful Coexistence: Reconciling Nondiscrimination Principles with Civil Liberties,” Chairman Martin R. Castro argued that Bible-believing Christians employ the phrase “religious liberty” as a code phrase for “discrimination, intolerance, racism, sexism, homophobia, Islamophobia, Christian supremacy or any form of intolerance.”

As Wall Street Journal columnist William McGurn noted, Castro’s comments illustrate the way many secular progressives insult Christians and Christianity.

In response to Christian shaming, Americans should be clear about two things.

First, there is nothing in the world wrong with being Christian in public. For Christians, our beliefs are deeply held convictions that should shape our identities, organize our lives, and motivate us to be good neighbors and citizens.

There is nothing wrong with Mike Pence, Tim Tebow, Nick Foles, or Tony Dungy making a connection between their faith and their public lives.

Thank God, we do not have a government-mandated religion we all must follow. Our varying religious beliefs – or non-beliefs – are not something we must hide or engage in secretly, behind closed doors, in the United States. Just as it would be wrong, un-American and unconstitutional to require an elected official to be an observant Christian, it is just as wrong to discriminate against an elected official like Vice President Pence for following a religion.

And why should NBC or its viewers care if Tebow, Dungy or Foles identify as Christians? Would they have the same reaction to somebody on television who identified as Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu or Jewish? As an atheist?

Similarly, there is nothing wrong with public prayer as a response to a harrowing event. The critics might think our calls to prayer are a way of avoiding the issue. But for our part, we’d turn the criticism around and say that our prayers are a more powerful form of activism than their social media flash-mobbing.

In fact, our obedience to the biblical command to pray is more important than the sum total of our tweets, radio shows and opinion pieces.

In the same way, there is nothing wrong with our quest for religious liberty, no matter what Chairman Castro says. That is why our Founding Fathers enshrined the free exercise of religion in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

Second, critics who shame Christians for being religious in public need to realize that they – the critics – are religious people who practice their religions in public, even if they don’t notice it.

That’s right. Each and every American, from the outspoken Christian to the died-in-the-wool atheist, has a “religion,” whether they use the term or not. Something or somebody sits at the center of the lives of everyone, shaping their identities, organizing their lives, and guiding their views of right and wrong. That something or someone functions as the god of that person’s life.

In other words, every human being ascribes ultimate worth to something or someone – to some person, ideal or ideology. If it is not God, it may be sex, money or power. Or anything else. Fill in the blank.

Every person is religious in this sense of the word, and every person’s functional religion will exercise a significant influence on his or her public life.

So let’s embrace it. Let’s stop shaming people for being transparent, for articulating publicly what they believe privately. And let’s start admiring them for putting their cards on the table, letting the rest of us see what it is that motivates them, and what makes all of us who we are.