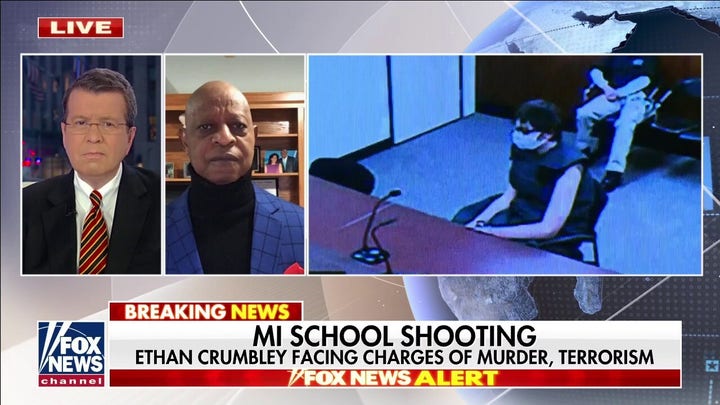

Michigan school shooting suspect faces terrorism charge, being tried as adult

Fox News correspondent Steve Harrigan has the latest on the charges against the Michigan school shooting suspect on 'Your World.'

There has been outcry over what some see as a disparity in the criminal charges following two recent mass-casualty attacks.

In Michigan, alleged school shooter Ethan Crumbley faces terrorism-related charges in the death of four students and the wounding of seven others. In Wisconsin, Darrell Brooks, alleged to have mowed down 68 people with his vehicle, killing six, faces more typical homicide charges rather than anything terrorism-related.

Some see prosecutorial bias at work here, but in fact the reason lies in America’s lack of a federal domestic terrorism statute. Do we need one? We do, and these two cases demonstrate why.

In a general sense, "terrorism" is defined as an illegal act committed to influence a civilian population or government. America has both federal and state terrorism laws. Historically, terrorism has been charged under the federal law. Since 9/11, however, 34 states have enacted their own terrorism laws, providing another option for police and prosecutors.

The problem is that federal terrorism law requires the perpetrator to be acting in support of a "designated foreign terrorist organization" (ISIS, Hamas, Hezbollah, al Qaeda, for example). If prosecutors cannot show that the perpetrator was acting "in support" of a foreign group designated by the State or Treasury Departments as being "terrorists," the federal law generally doesn’t apply.

In both the Wisconsin and the Michigan incidents, no such link to a designated terrorist organization has apparently been found; a federal terrorism charge is therefore off the table.

What police and prosecutors will then do is look to the possibility of charges at the state level, where the "foreign organization" requirement is generally not required. And here, then, our disparity: Michigan has a state-level terrorism law; Wisconsin does not.

As such, Crumbley now faces a Michigan state terrorism charge. Brook’s Wisconsin state charges invoke no element of terrorism.

A better solution is for the feds to jettison the "designation" prong and follow the states’ more practical approach.

One way to cure this disparity would be for every state to enact its own terrorism statute. Simpler, however, would be for the federal government to enact a domestic terrorism statute, giving federal prosecutors this option coast-to-coast.

There will be challenges. An oft-invoked impediment to such a federal law has been the "designation" aspect. Which groups would we designate as "domestic terrorists"? And what arm of the government would make these designations?

The country can usually agree on what a foreign terrorist group looks like. In today’s political environment, however, one could hardly conjure a more polarizing issue than deciding who among America’s various pressure groups qualifies as a "terrorist."

A better solution is for the feds to jettison the "designation" prong and follow the states’ more practical approach. In New York State, for example, a long list of typical criminal charges, including murder and arson, can be charged "as a crime of terrorism" if the intent to influence the civilian population or the government is present. No prior "designation" is required.

This is generally the construction state charges follow across the country (including in Michigan), and it works. The basic formulation of the federal statute would be:

Intent to Influence + Certain Crimes = "Terrorism"

The written law would need to list which acts would qualify as the required crimes. If arson, for example, is included in the list (which of course it would be), and if it can be shown that the arson was committed to influence the civilian population or an arm of the government, we would then have a federal crime of terrorism.

This is hardly a revolutionary approach. Aside from the states’ models, this is the basic structure of federal hate crime statutes, which have been shown to work in instances like the Wisconsin and Michigan attacks.

In the case of Dylann Roof for example, who in 2015 killed nine African American congregants in a South Carolina church, federal prosecutors could not charge terrorism – no evidence of Roof acting to support a foreign designated entity could be shown. As such, federal prosecutors charged him with 24 hate crime counts.

Similarly, in 2018 when Robert Gregory Bowers shot and killed 11 congregants in a Pittsburgh synagogue, federal prosecutors charged dozens of hate crime counts – but no terrorism.

Using the state model for a new federal statute avoids the fraught issue of criminalizing opinions among our domestic population. Instead, the criminal acts themselves are deemed terroristic, not the group involved.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

The First Amendment remains perhaps the most unique and important aspect of the American system; there’s a reason it’s first. A federal law modeled on the approach most states take would be the best way to safeguard free speech protections, while still prosecuting those who wish to commit violence for the purposes of a political statement.

Having such a statute in place would have allowed the possibility of Dylann Roof, Robert Bowers, Ethan Crumbley and Darrell Brooks all to be prosecuted under a single federal charge with the word "terrorism" at the top of their indictments. On a commonsense level, does this not feel closer to justice than our current regime?