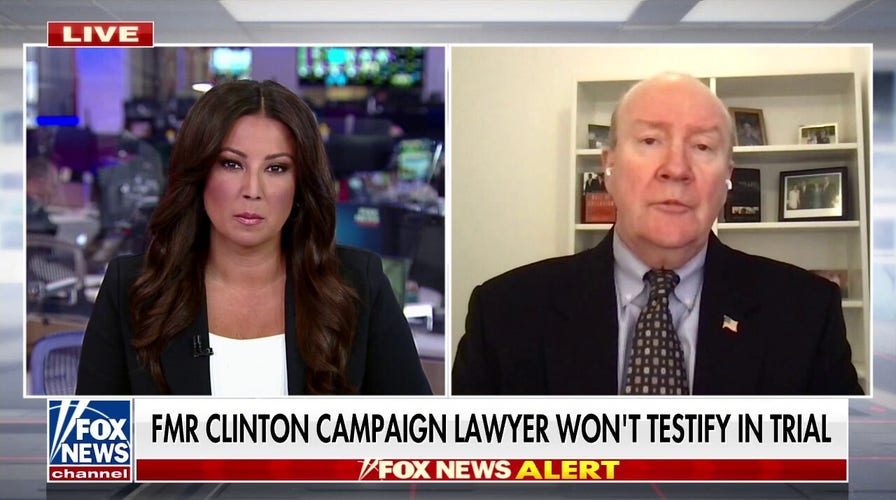

Andy McCarthy: Sussmann not testifying shows 'confidence' in defense

Fox News contributor Andy McCarthy discusses possible reasons Sussmann won't testify in his own defense.

In a predictable but nevertheless damaging blow to the prosecution, the judge in the Michael Sussmann trial ruled Thursday that the government may not argue that Sussmann’s text message to the FBI’s then-general counsel constitutes the false statement charged against him. Rather, prosecutors must rely on their evidence that Sussmann made the false statement the following day, when he met with the general counsel, James Baker, at the latter’s FBI office.

Sussmann, a top Democratic Party lawyer, allegedly lied by telling Baker that he was not representing any client when, on September 19, 2016, he brought Baker what he purported was evidence showing that Donald Trump, the GOP’s then-candidate for president, had established a communications back channel with the Kremlin, via servers at Russia’s Alfa Bank.

MICHAEL SUSSMANN WILL NOT TESTIFY IN TRIAL, DEFENSE RESTS AHEAD OF CLOSING ARGUMENTS

In reality, Sussmann was representing the Clinton campaign, as well as a tech executive, Rodney Joffe, who had compiled the data Sussmann delivered to Baker.

Both sides have now rested in the trial, which began two weeks ago. Summations are imminent.

The smoking gun establishing that Sussmann made a false statement appears to be the text message Sussmann sent Baker the night before their meeting. Sussmann reached out to Baker because the two are friends, both having worked for many years in the government as Justice Department national security lawyers. The September 18 text from Sussmann stated:

"Jim — it’s Michael Sussmann. I have something time-sensitive (and sensitive) I need to discuss. Do you have availability for a short meeting tomorrow? I’m coming on my own — not on behalf of a client or company — want to help the Bureau. Thanks." [Emphasis added.]

But the problem for Russiagate Special Counsel John Durham is two-fold.

First, his prosecutors did not have the text, or even know about it, when they indicted Sussmann in September 2021. Consequently, the text is not pled as a false statement in the charging document. The indictment, instead, charges that Sussmann made the false statement while meeting in person with Baker on September 19.

That makes the case much more challenging for prosecutors. The 20-minute meeting between Baker and Sussmann was not a standard FBI interview. It was more like a short, one-on-one meeting between a pair of old friends. The session was not recorded, and there was no second FBI official on hand to take notes and clarify any ambiguities.

Baker was an FBI lawyer, not a trained investigator. In a standard federal criminal investigation, witnesses are interviewed by two FBI agents, with one leading the questioning and the other taking notes. The agents then write a summary report (Form 302), based on their collective memory. If there is ever any dispute about what the witness said, there are then two trained agents available to testify.

In a false statements case, the prosecution must prove the statement that was allegedly made, beyond a reasonable doubt. On that score, Baker did indeed testify about Sussmann’s insistence that he was not bringing anti-Trump information to the FBI on behalf of any client. Nevertheless, the defense effectively showed that Baker has made inconsistent statements over the years when asked about his meeting with Sussmann, in both the congressional hearings and internal Justice Department inquiries.

That is, prosecutors must now rely mainly not on the text but on Baker’s recollection, and his recollection has been sketchy.

Durham’s second big problem is the five-year statute of limitations. He was right up against the deadline to file charges when he indicted Sussmann in September 2021. Six months later, when interviewing Baker in preparation for his upcoming testimony, Durham asked Baker – who no longer works for the government – to check his personal records for any information that might be relevant to the case. At that point, Baker checked his stored text messages and found several from Sussmann, including the smoking-gun text from September 18, 2016.

Ordinarily, a prosecutor who’d received such ironclad proof of a false statement would simply go back to the grand jury and obtain a superseding indictment, charging the text as a separate false-statement count.

In this instance, however, the five-year statute of limitations had already lapsed. Durham was not in a position to add new charges related to events in September 2016. In fact, even superseding the indictment to describe the text, rather than separately charging it, would have raised legal objections that prosecutors were changing the indictment after the statute of limitations had run.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

Michael Sussmann, a cybersecurity lawyer who represented the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign in 2016, leaves federal courthouse in Washington, Monday, May 16, 2022. A jury was picked Monday in the trial of a lawyer for the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign who is accused of lying to the FBI as it investigated potential ties between Donald Trump and Russia in 2016. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

Durham was thus stuck with the indictment as it was written, before the existence of the text was known.

Importantly, this does not mean the text is out of the case completely. To the contrary, prosecutors will still be permitted by Judge Christopher Cooper to argue that the text is strong evidence that Baker is correct that, at the September 19 meeting, Cooper insisted that he was not representing a client. Prosecutors will point to the text right before the meeting, as well as Baker’s telling other FBI officials right after the meeting that Sussmann had said he was not representing a client. Based on that, Durham’s team will argue that the proof of Sussmann’s false statement is convincing.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Nevertheless, prosecutors will not be permitted to argue that Sussmann is guilty of making a false statement solely based on the text. To convict him, the jury must be convinced that Sussmann made the false statement at the meeting with Baker.

That makes it a much tougher case for Special Counsel John Durham.