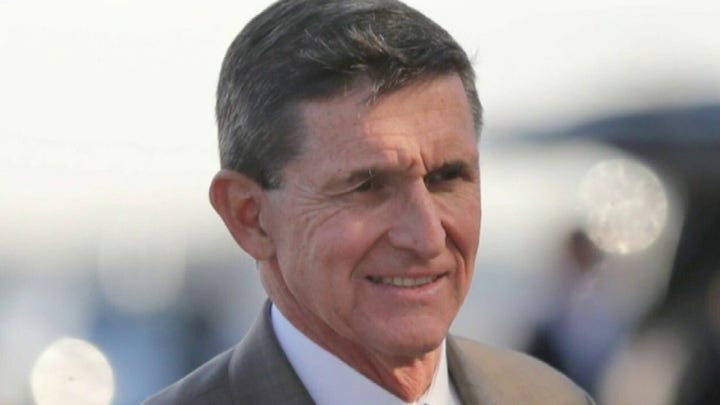

Trump announces 'full pardon' for Gen. Michael Flynn

President pardons former national security adviser; Neil Cavuto has the latest on 'Your World'

It was only a matter of time, once it became clear that the election was lost, that President Trump would pardon retired Army Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, who fleetingly served as his first national security adviser. The president did so Wednesday.

Months ago, the Justice Department moved to dismiss Flynn’s prosecution on the ground that there was no basis to investigate him in the first place – a point I started making in 2017. But the Justice Department ran into an angry jurist and a quirk of federal law.

U.S. District Judge Emmet Sullivan was deeply opposed to the dismissal of Flynn’s case. In connection with the investigation conducted by Special Counsel Robert Mueller, Flynn had initially pleaded guilty in late 2017 to one count of making false statements to investigators. That plea was taken by a different judge, and the case was then reassigned to Judge Sullivan.

TRUMP ANNOUNCES PARDON OF FORMER NATIONAL SECURITY ADVISER MICHAEL FLYNN

In the aftermath of the plea, there was protest by Flynn supporters that he had been railroaded. During the transition to the Trump administration in December 2016, Flynn — as the designee to be the incoming president’s top national security aide — had entirely appropriate communications with foreign officials, including Russia’s Ambassador to the U.S. Sergey Kislyak.

In the growing “collusion” hysteria, however, it was rumored that these contacts were somehow illegal and may have involved a corrupt deal to undo sanctions against Moscow imposed by President Obama as a payoff for Russia’s meddling in the election for Trump’s benefit.

It is noteworthy that the collusion narrative was a creation of the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign, abetted by illegal classified leaks to the media from intelligence officials. Indeed, the revelation that Flynn had been in communication with Kislyak was based on a January 2017 leak to The Washington Post.

More from Opinion

Although there was no evidence that Flynn was either a clandestine agent of Russia (which could have been the proper basis for a counterintelligence investigation), or had committed any penal offense (which could have predicated a proper criminal investigation), FBI Director, James Comey dispatched two agents to interview Flynn at the White House on January 24, 2017 — Flynn’s first full day as national security adviser.

The interview had not been cleared with the Justice Department or the White House, as protocols required.

Plainly, the interview was a perjury trap. FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe softened Flynn up by discouraging him from getting counsel. The interviewing agents, led by Peter Strzok, schemed to avoid giving Flynn the FBI’s standard advice to interviewees about the nature of the interview and the fact that any false statement could result in prosecution.

In my view, the objective was, at a minimum, to get Flynn fired or otherwise sidelined from any involvement in the Russia investigation. The FBI’s overarching plan, initiated by the Obama administration, was to continue investigating the bogus Trump-Russia angle, in hope of developing a basis to impeach or prosecute President Trump. That would have been difficult to do with Flynn — an experienced official and former head of the Defense Intelligence Agency — at the National Security Council helm.

Nevertheless, the interviewing agents concluded that Flynn did not lie. There were some inconsistencies between his recitation of the Kislyak conversations and the transcripts, but these were chalked up as normal failures of recollection.

The recorded conversations were said to have been inconsistent with Flynn’s report to Vice President Mike Pence of what had been discussed, although even that is debatable. This led President Trump to fire Flynn. But the FBI never sought to prosecute Flynn during Comey’s tenure because the bureau did not believe he had intentionally made false statements.

The Flynn investigation, however, was revived by Mueller’s team, which was largely staffed by activist Democrats, several of whom had served in the Obama Justice Department. They heavily pressured Flynn to plead guilty, including, according to Flynn’s current counsel, threatening to prosecute Flynn’s son.

When he retired from the Army, Flynn started a private intelligence firm; his son was employed there, and the firm did some work for foreign countries, including Turkey, though it was not registered as a foreign agent. Investigators suggested that there could be criminal liability in the firm’s failure to register and statements made to the Justice Department in that regard.

fter Flynn pleaded guilty and the case was subsequently assigned to Judge Sullivan, the latter expressed concern about the public suggestions by Flynn supporters that he had been coerced into pleading guilty. Sullivan thus took Flynn through what, essentially, was a second guilty plea.

In thorough questioning by Sullivan, Flynn insisted that he was pleading guilty voluntarily, that he was doing so because he was in fact guilty, and that he had no complaints about his counsel or the prosecutors.

Flynn indicated in early 2018 that he was prepared to be sentenced and put the awful chapter behind him and his family. As a first offender who (a) should not have been investigated, (b) had pleaded guilty to a dubious process crime, and (c) was a decorated combat commander with a distinguished 30-year history of service to the United States, it should have been an easy sentence, involving no jail time.

Yet the sentencing did not happen, because Judge Sullivan became unhinged. At an outrageous hearing, the judge suggested that Flynn had committed treason (later apologizing for that slander). He also implied that if Flynn did not provide additional cooperation to the Mueller prosecutors (with whom Flynn had been cooperating), a prison sentence could be in the offing.

This launched a transition in which Flynn first changed his mind about pushing to be sentenced and ultimately decided to fight the case. He eventually dismissed the lawyers who had represented him through the plea, retaining the combative Sidney Powell.

Powell pushed aggressively for discovery that the government had not previously provided Flynn, and moved to have the case thrown out, contending that the FBI and the prosecutors had committed outrageous misconduct, pervasively violating Flynn’s due process rights.

In the interim, in 2019, President Trump replaced Jeff Sessions with William Barr as attorney general. Barr authorized a still-ongoing investigation into the politicized origins of the Trump-Russia probe. This also came to include the appointment of an outside prosecutor, St. Louis U.S. Attorney Jeff Jensen (a former FBI agent), to review the Flynn case.

Besides confirming that there was no appropriate basis for investigating Flynn in the first place, Jensen uncovered significant improprieties in the FBI’s interview of Flynn, including the still unexplained departures from FBI procedures in the writing and editing of the report of Flynn’s interview (the so-called FBI 302 form).

Disclosures also showed that FBI Director Comey had discussed Flynn’s case at a White House meeting on January 5, 2017, which featured the highest-echelon political and law-enforcement officials of the Obama administration: President Obama, Vice President Joe Biden, National Security Adviser Susan Rice, and Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates.

Notes from the meeting suggest that the possibility of prosecuting Flynn under the Logan Act — a likely unconstitutional provision that has never been charged in the 150-year history of the Justice Department — was discussed.

The improprieties surrounding Flynn’s investigation led the Justice Department to move to dismiss the Flynn case. This decision, however, crashed into a foible of federal law. Although the Constitution gives the executive branch unfettered discretion over prosecutorial decisions, including which cases to abandon, the federal rule governing dismissal purports to require the prosecutor to obtain “leave of the court.”

This mandate is probably unconstitutional, but was inserted primarily to protect defendants from prosecutorial abuse (for example, dismissing a case that is going badly, so that it can be re-charged at a later, more opportune time). It does not apply when a defendant concurs in the Justice Department’s dismissal motion because the case is being dismissed with finality.

Judge Sullivan, however, resorted to this quirk in the rule to refuse to act on the dismissal motion. Despite the Justice Department’s thorough explanation for its decision (which it is not required to give in such detail), the judge intimated that motion to dismiss Flynn’s case, despite two guilty pleas, was potentially a corrupt deal.

Sullivan even retained a former federal judge and unabashed Trump critic, John Gleeson, as a friend of the court for the purpose of developing a legal theory that Sullivan had lawful authority to sentence Flynn — notwithstanding that the only legitimate prosecutorial authority, the Justice Department, wanted the case dropped.

For a time, it seemed that the dismissal would finally happen. A divided panel of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia initially issued a writ of mandamus, directing Sullivan to dismiss the case.

But that directive was withdrawn by the full court (heavily dominated by Democratic appointees), which declined to find that Sullivan had acted inappropriately. The appellate court returned the case to Sullivan, with the expectation that he would move expeditiously and follow the law.

Alas, Sullivan had no intention of acting expeditiously or following the law. He clearly did not want to dismiss the case, and realized that no one would force him to do it on a short timeline. If he waited long enough, and Trump lost the election, Sullivan calculated that Trump would have to pardon Flynn or risk having a Biden Justice Department withdraw the dismissal motion. This would deny Flynn the exoneration on the official court record that he hoped to get from the Justice Department, which had brought the case against him.

It was not Judge Sullivan’s place to do that, no matter how personally convinced he may be about Flynn’s guilt or the wrongness of the Justice Department’s dismissal decision. But the procedural rule, coupled with the solicitude of the appellate court, gave Sullivan the whip hand. He used it in a most unseemly manner.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR OPINION NEWSLETTER

Judges are supposed to be impartial arbiters whose main function in a criminal case is to protect the rights of defendants from government overreach and intimidation.

The pardon, nonetheless, expunges the case against Flynn. As a matter of law, it is as if the charges were never brought, as they should never have been.

A statement released late Wednesday afternoon from White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany said: “General Flynn should not require a pardon. He is an innocent man.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The statement went on to say that Flynn “is yet another reminder of something that has long been clear: After the 2016 election, individuals within the outgoing administration refused to accept the choice the American people made at the ballot box and worked to undermine the peaceful transition of power. These efforts were enabled by a complicit media that willingly published falsehoods and hid inconvenient facts from public view, including with respect to General Flynn.”

Thus ends an unsavory chapter.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FROM ANDREW MCCARTHY