On the 30th anniversary of the Los Angeles riots that shook America in 1992, Fox News asked Michael P. Downing, a former top cop with the Los Angeles Police Department for his thoughts and insights.

Los Angeles erupted after the Simi Valley jury acquitted Officers Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind and Theodore Briseno for the beating of Rodney King. The riots lasted six days. When the smoke cleared, 63 people were killed, 2,383 were injured and more than 12,000 were arrested. The property damage was estimated to be well over $1 billion.

Downing was a young man on the streets during the riots. He went on to serve 35 years with the LAPD and reached the department’s highest levels, including commanding officer, deputy chief, and interim chief of police.

What follows is a Q&A that has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. We strongly encourage you to watch the accompanying video so you may hear Downing in his own words.

Q: Where were you when the Los Angeles riots began?

A: I was a lieutenant assigned to 77th Division. I happened to be on vacation that week studying for the promotional exam and saw what was happening on the news. I immediately got in my car and drove to the station. I got off on Florence Avenue from the 110 freeway. There were gang members in the underpass as I was going through, there were gunshots all around.

I made it to the station. While I was on vacation, Lt. Mike Moulin had been put in my place, and I basically went into the station and got ready and went out to the command post at 52nd Street and Arlington Avenue.

(Note: The 77th Division was involved in the initial incident that sparked the riots. Two officers requested assistance in apprehending 16-year-old Seandel Daniels, who had thrown an object at their car. Moulin and approximately two dozen officers arrived to arrest Daniels. The gathering crowd became visibly upset at what they saw as the rough handling of Daniels. Moulin, fearing one of his outnumbered men would resort to deadly force, ordered his men to retreat.)

I'VE LIVED IN LA MORE THAN 30 YEARS AND I DON'T FEEL SAFE ANYMORE

Q: Was the LAPD prepared for the possibility that its four officers would be acquitted for the beating of King?

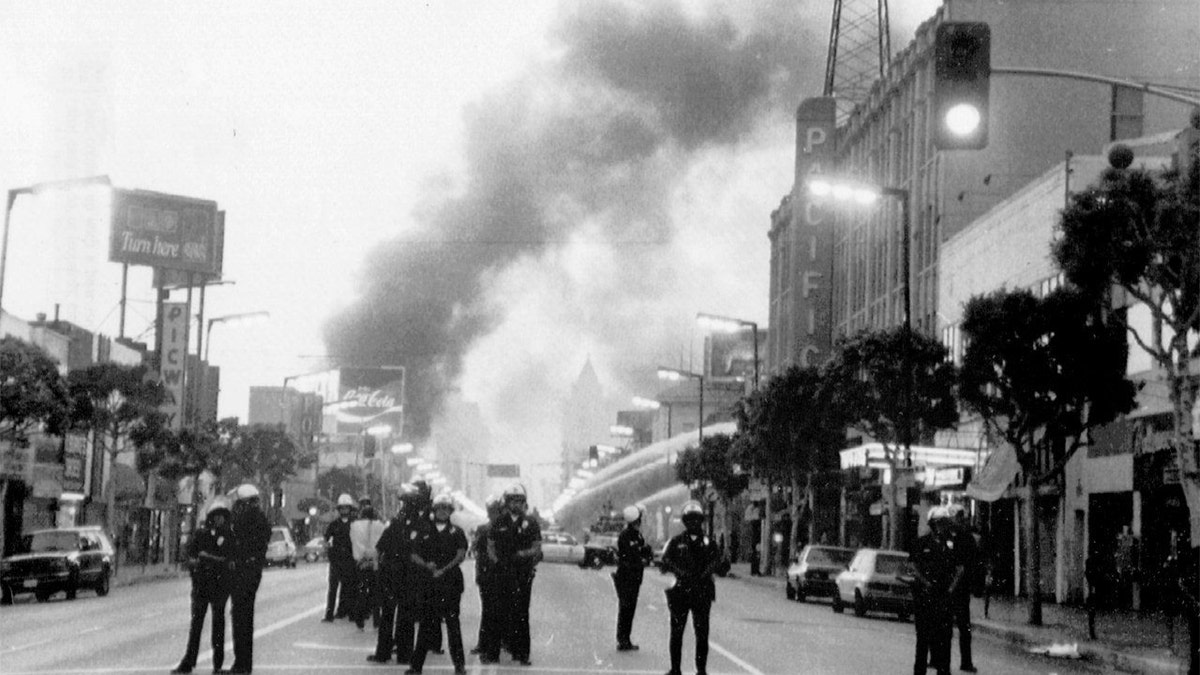

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA - APRIL 30: Police officers stand watch over burning building in West Los Angeles following looting and arson reaction to the acquittal of four LAPD officers in the Rodney King incident. Photographed April 30, 1992 in Los Angeles, CA. (Photo by Fred Sweets/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

A: We were worried that there was going to be isolated incidents throughout the city when the verdict was announced. There was some preparation. But you have to remember, back in that time, Police Chief Daryl Gates and Mayor Tom Bradley hadn’t spoken to one another in a couple of years. There was a good division between the mayor's office and the police department, and when we talk about putting credits in the bank and building trust with communities, it was strained. But I had no idea that it would light off like it did in terms of what we saw throughout the city.

Q: What was the most vivid memory you had?

A: It was a surreal scene for me to believe that we lived in the United States under a democracy, to see pure anarchy occurring before my eyes. To see black soot falling from the sky, to driving down streets and see gunfire come out of alleys, to see stores being looted, to see the Korean businessmen up on roofs defending their stores, firing weapons down, to seeing 52 dead bodies in a parking stall at the command post right next to the food truck that was feeding the cops and the first responders. That was a scene that was more conducive to what you would see in war than what you would see in a democratic society.

Q: Did you understand the anger of the rioters or were you more concerned with upholding law and order?

A: It's a balance. I was absolutely concerned with the anger. I was concerned hearing Bradley say: "Go to the streets and voice your anger and show your anger." That concerned me a little bit—a lot actually. I knew we had to restore order. I knew that it was anarchy, that it affected the entire city of Los Angeles. Buildings were burning, innocent people were getting hurt, police were getting hurt.

I knew that there was a balance. In public service and public safety and policing, we're not soldiers. We don't have enemies. We're public servants and most of the time, you control chaotic things by inspiring values and providing education and mobilizing resources.

In this case, cops had to become soldiers for a period of time and control through force and fear … When we have to become a different role and control through force and fear, we've failed in certain areas.

I was disappointed, I was disheartened, I was very sad at the scene that this had come to.

Q: How did other LAPD officers react to the acquittals of the officers involved in the beating of King?

A: Now that I've been retired for five years – I did 35 years with LAPD – I've come really to notice the division even within law enforcement on perspectives and opinions. More shocking than anything – and I think looking back to 1992 and listening to discussions in roll calls and discussions in locker rooms and discussions at the gas pumps at the time – I noticed that there was some division and different perspectives.

I don't know if it was freely talked about as much as it is today in different circles, and I think that's one of the big differences that I see today, especially with social media. You see the opinions of people that you never thought existed when you were on the department, especially in 1992. Had we had social media platforms, the Facebooks, the Instagrams, the Twitters, the LinkedIns back then, I think it would have been a lot more apparent, and not in a good way.

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA - MAY 1: Police guard Hollywood Boulevard after the Rodney King incident sparked riots. Photographed May 1, 1992 in Los Angeles, CA. (Photo by Dayna Smith/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Q: What do you think is the biggest lesson to be learned from the riots?

A: We all know that democracy is fragile. I believe that the relationships with police in communities is fragile, that you will always have the cheerleaders, you'll always have the supporters, but you need to continually put credits in the bank with all communities. You can't just say "the community" today. It's communities because they're all different. They all have different experiences with government, with law enforcement, and you have to feed those communities with support, with services, with a voice, with interaction, with town hall meetings, with problem solving efforts, with access to government.

You can never stop because you know that a crisis is always on the horizon. You're always going to have a storm come, and you're going to have to take those credits out of the bank. You've got to make sure you're not bankrupt because, in 1992, we were bankrupt with certain communities in the city, and we didn't have any more stature.

(Note: The gang sweeps during the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics and during Operation Hammer, which began in 1987, led to the arrests of tens of thousands of people. Many were not charged.)

Social scientists believe that these things happen every 30 years. We certainly hope it doesn't happen like that today, but I do know that even when you look at Jan. 6, 2020, as kind of an analogy and leading up to the 2024 elections, I'm very worried about what could happen in this country.

I know the Joint Chiefs of Staff are very worried because they met about the potential for a civil war leading up to the 2024 election, and I know that's an extension of what we saw in 1992, but it's more of a national picture versus a localized picture.

The protests and demonstrations for this country are a good thing. For police and first responders and public servants to facilitate protests, so that they're orderly, so people can speak their mind and if they need to appeal or protest against a policy or a governmental procedure or something, that needs to be in place. There needs to be listening mechanisms in place and there needs to be some type of action taken to address them.

That's what our democracy was built on. If you suppress the ability to protest and demonstrate, you're going to have a pressure cooker type of problem where the lid is going to be blown off and you're going to have another riot.

Q: Has the LAPD improved in the years since the riots?

A: I think the Los Angeles Police Department has improved in many ways. I think the one mechanism that really created a lot of evolution and improvement and reform within the police department was the consent decree that we were under for 10 years.

That really concerned me when we went through this whole debate about defunding the police and starting over. You can't throw the baby out with the bathwater. Everybody knows that reform is a continual thing and that probably the greatest adversary we have is complacency and status quo. We can never have that.

But if you look at the type of organization, even back to the 1930s, where we were a politically controlled police department and then we went into a reform police department and then we went into the era of being a professional police department and then we went into the era of community-based policing police department and we've played with this other era of intelligence-led or predictive-led policing, but the foundation of policing is always based on communities.

The one principle that holds true is people are the police and police are the people. The police department has to reflect what the people look like, how they feel, what their values are. We can never move away from that idea.

Have we improved? When you look at the consent decree, 187 paragraphs of improvement were written in that consent decree. I think when we ended it 10 years later, we were somewhere in the neighborhood of 97% compliance.

There's always the potential to slip and go back or default back to where you were. That is eliminated by or mitigated by excellent leadership, by continually looking back and critiquing, by having people who don't necessarily agree with you, to have them be a voice and be reflective on that voice and listen to the critiques.

Civilian oversight is so important to the Los Angeles Police Department. I wish there was a better way to have civilian oversight where they weren't so much attached to the mayor's office and/or to city council but they did reflect the values of a civilian commission that would oversee and be the board of directors of a police department.

I think some of the problems that we've gone back to is we've become politicized … When you politicize a police department the way it's been politicized today, you see what happens in Los Angeles and you're seeing what's happening to it now. Crime is going up, violence is going up, and the physical stature of the community looks horrible with homeless encampments. It's not good for the homeless.

It's because the police hands have been tied and there hasn't been a plan and there hasn't been good leadership. We need to get back to the basics. Communities need to participate. We need to listen to communities. We need to create better partnerships in communities. We need to solve these quality of life problems and the big things will take care of themselves, but we need to get back to basics.

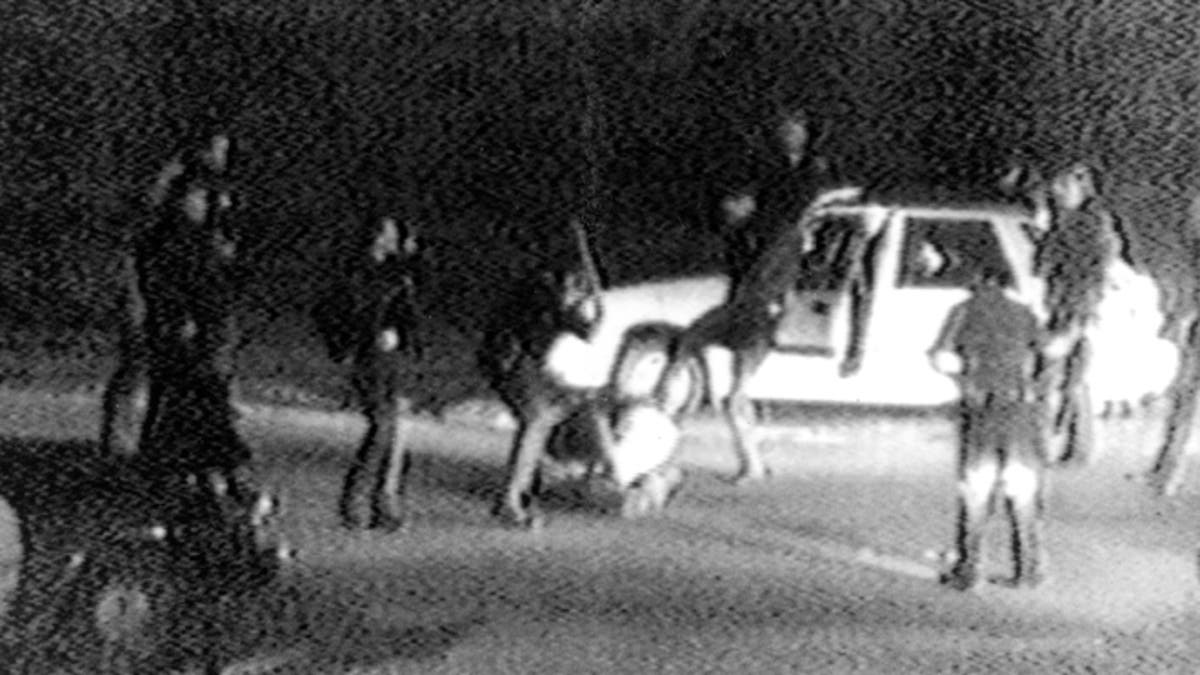

March 31, 1991: FILE - This image made from video shot by George Holliday shows police officers beating a man, later identified as Rodney King. (AP/Courtesy of KTLA Los Angeles)

What concerns me is that if we don't and this continues to devolve and continues to whirl in this downward spiral, we're going to be back to where we were 30 years ago.

Q: How has the LAPD sought to become more reflective of its communities?

A: We got to a point where I believe that we didn't really have to say we have an affirmative action policy and we need these certain percentages in the department because we had those percentages and it was created through equal opportunity, through recruitment, through giving everybody opportunities for promotion.

I think we had to reflect that diversity up through the rank structure of LAPD, which is happening. A good example is my watch commander when I was a captain in the Hollywood Division. Before I retired, she became my boss. She was an assistant chief and I was a deputy chief. I was thrilled, because I had a little piece of that to give her, to see her succeed. It was fantastic.

I think when you look at the diversity of women on the police department, it looks pretty good. I think we have to improve a little bit when it comes to minorities. I think we always have those goals and I think there's opportunities for everyone now. It's not perfect. We need to continue to reform.

But there was a point where we had to say, "Let's manage the diversity now so that we can reflect it up through the rank structure and let's not stigmatize it so that we create a system where we're just promoting people or recruiting people to fill a quota." Because then that creates really a stigma against that person because there's a belief, "Well, you only got this position because of your ethnicity or your gender." That could be equally as damaging.

Q: The Los Angeles Riots changed Los Angeles forever. How did it change the city? How did it change you?

A. How it changed me? It made me believe that however good I thought we were, we had a long way to go and that we had a lot of improvement to do. And that sometimes you have to let go of being right and create enough room in the glass to listen to people, react to people, allow people to see change and reform take place and be accountable to that.

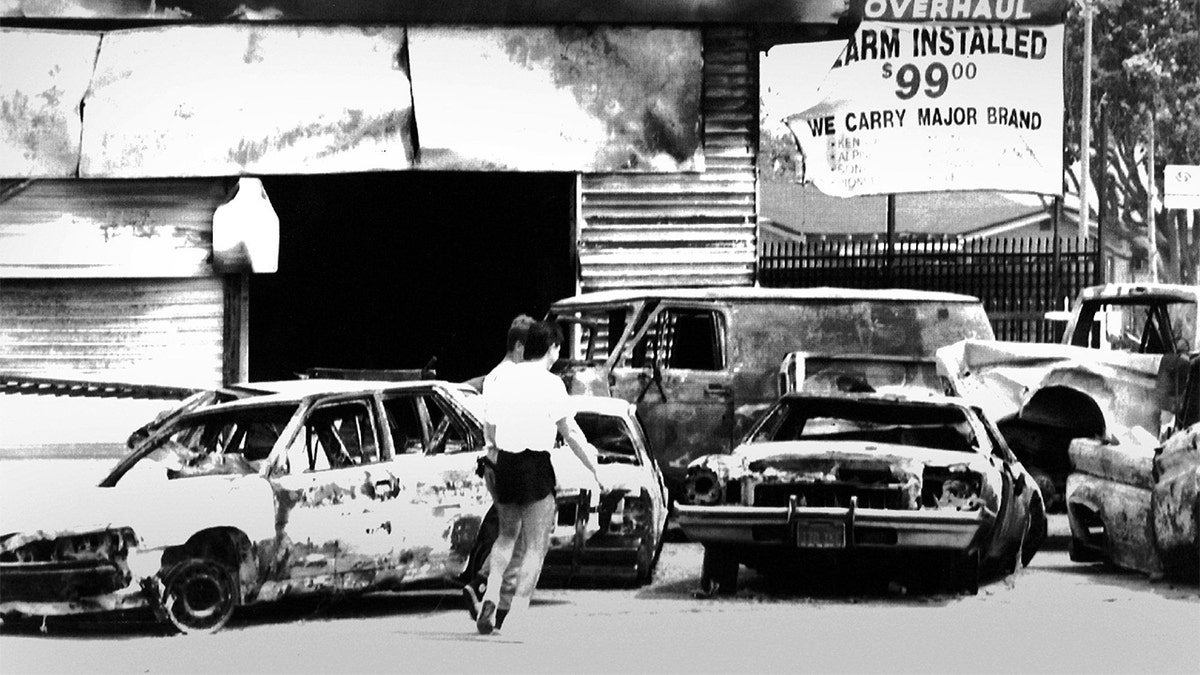

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA - MAY 1: Burned-out cars at the intersection of Normandie and Florence in South Central Los Angeles after the Rodney King riots. Photographed May 1, 1992 in Los Angeles, CA. (Photo by /The Washington Post via Getty Images)

When you get inculcated in a culture, sometimes that culture doesn't serve you very well and you need outside influences to continually question what you're doing … to make sure that you don't get stuck in this groupthink type of mentality.

Are arrests a really good measure of success? I've learned that it's probably not. You know, leading up to the riots, we went through all these different initiatives, battle plans and operation plans and it didn't serve us very well, because it created more of a military mentality, a quasi-military mentality … We should be leaning much more toward public service and serving with a public servant's heart and understanding the nature of what communities really need and what they really want in terms of how we approach our job.

It made me think that's the type of leader that I want to be. I want to be an inclusive leader, a coach and somebody that listens to a variety of opinions.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

How it changed the city … I think the city still is at the point where it's fragile and I think you've seen what's happened over the last nearly 10 years or so … If you take your eye off the ball, you're going to default back to what it was. I think that's what we're seeing right now.

In the 2000s, we had homicides that were under 300 per year, whereas in the '90s, they were almost over 1,000 I think a year. Obviously, 300 is way too many. One is way too many. The violence is starting to curb up again. The physical stature of the communities is starting to look bad again. There needs to be a reset. We need to refocus on how we're approaching this problem while still keeping compassion and empathy toward under-served communities and making sure we push social services and mental health and triage those communities.

It's this idea of how do we achieve this rule-based approach and a care-based approach so that we don't have anarchy but we don't have lack of freedoms as well, but that we provide inspiration to communities to become good partners, so that we're doing it together and it's not just a police department problem.