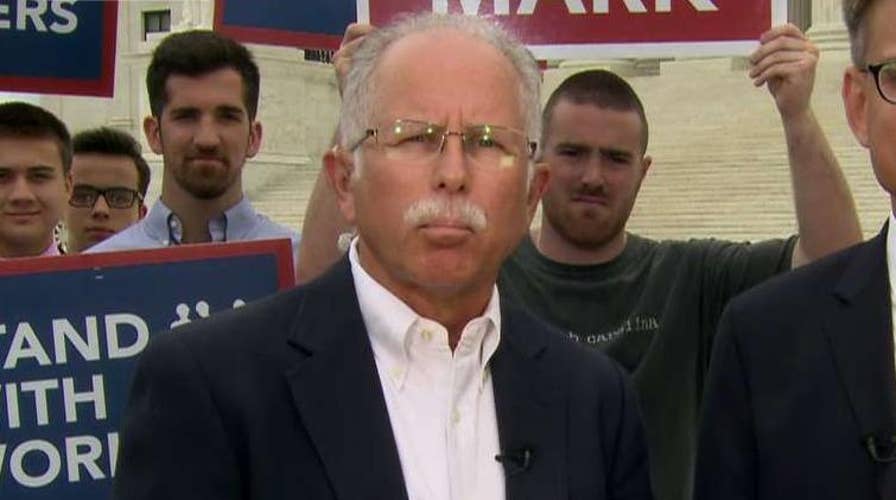

Mark Janus on Supreme Court ruling: I'm ecstatic

Janus v. AFSCME plaintiff Mark Janus and attorney Jacob Huebert on the Supreme Court ruling on public sector unions.

Thomas Jefferson said, “to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves and abhor[s] is sinful and tyrannical.”

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito echoed those words in his majority opinion in Janus v. AFSCME, a decision that one year ago abolished the longstanding practice of forcing public workers to pay money to the union at their workplace whether they were a member or not. Specifically, the decision stopped compelling the plaintiff, Illinois state worker Mark Janus, to financially support AFSCME’s politics, which were not his own.

Illinois offers a glimpse into what the Janus ruling has meant for workers and taxpayers after its first year.

Many public-sector workers in Illinois have indicated they don’t want to continue paying dues. In fact, more than 8,000 public employees stopped sending money to AFSCME Council 31 – that’s at least 12 percent of employees represented by AFSCME, the largest and most powerful government union in the state.

Each of those 8,000 workers had their own reasons for choosing to stop paying the union. Maybe they wanted to keep more of their hard-earned money to spend on their family. Maybe they didn’t like the union’s demands on taxpayers. Or maybe they didn’t like the union’s politics.

Whatever the reason, they aren’t alone – nearly 15,000 public employees from just two of Illinois’ largest government unions have chosen to stop sending money to their unions.

The truth is that government unions are inherently political animals. This was made clear during the Janus hearings when Justice Anthony Kennedy asked AFSCME’s attorney, “If you do not prevail in this case, the unions will have less political influence: yes or no?” The attorney agreed the union would indeed have less power.

“Isn’t that the end of this case?” Kennedy exclaimed.

The proof is in the numbers. AFSCME spent just 17 cents of every dollar on representing workers in 2018. The rest went to overhead, politics and other leadership priorities.

AFSCME Council 31 and its national headquarters spent over $213 million on political activities and lobbying between 2013 and 2017. In 2018, Council 31 spent over $5.1 million on Illinois politics alone.

Undoubtedly, government unions’ focus on politics and protecting their special interests will only increase in a post-Janus world. It’s already happening in Illinois.

After the Janus decision came down, government unions in Illinois were quick to pursue a far-reaching legislative agenda. And with willing partners in the governor’s mansion and general assembly, government unions attempted to shepherd through bills that would compromise their members’ privacy while at the same time preventing members from receiving information from anyone other than the union. Another proposal would allow AFSCME to give “orientations” to all new government hires. None of these efforts are meant to empower workers, but rather to keep them in the dark about their Janus rights.

AFSCME has also used its muscle to wield political control. After years of deadlock between former Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner and AFSCME over the union’s exorbitant demands, Gov. J.B. Pritzker immediately boosted their contract by $3.6 billion – which includes 11.5 percent raises over four years.

Illinois state workers are already among the highest-paid in the country and make significantly more than the average taxpayer responsible for supporting them.

What the union brass and their Statehouse allies fail to realize is that this continued overpromising and overspending puts workers’ own retirements and livelihoods at risk in the long term. The state’s pension funds could become insolvent by 2040 if lawmakers fail to reform the retirement systems, according to original Illinois Policy Institute actuarial analysis. It’s hard to cut checks with no money in the bank.

AFSCME isn’t the only union forcing bad policies on government and taxpayers, and it isn’t unique in seeing its members flee. Nearly 7,000 public school educators have stopped sending money to the Illinois Federation of Teachers – that’s more than 6.7 percent of employees represented by the union.

In Janus’ first year, the ruling meant a lot of different things to different people. Union leaders viewed the case as an existential threat; other critics caricatured it as “union-busting.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

But Janus was always about something much more universal than that. It was a case that sought to restore workers’ basic freedom to choose how they spend their money and which causes they support.

The coming years will show us what workers choose to do with that freedom – and how government unions fight to limit it.