Bill Clinton: John Lewis has left us his marching orders. Let's salute, suit up and march on

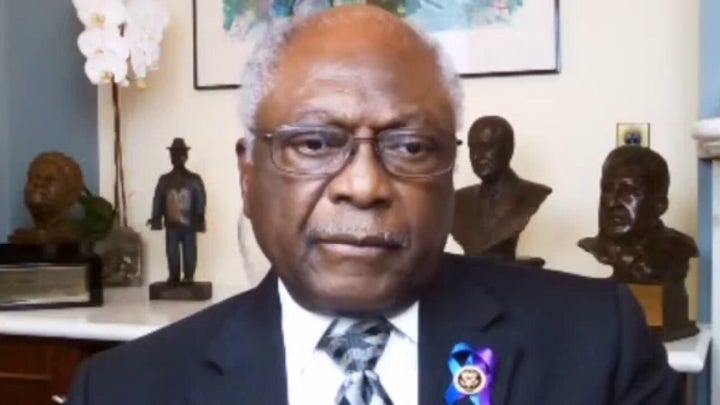

Former President Bill Clinton delivers a tribute to Rep. John Lewis at his funeral service in Atlanta, Georgia.

“Hello, Congressman.”

“Today, I’m the ‘Boy from Troy,'” John Lewis replied with a mischievous grin.

It was October 2011. The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial had just been dedicated in Washington, D.C.

POSTHUMOUS LETTER FROM JOHN LEWIS PUBLISHED

Lewis could see I didn’t get the joke from the confused look on my face.

“That’s what he called me,” the congressman explained.

Yes, Dr. King created a rhyme to tease the young John Lewis. He wanted to lovingly remind him he would always be in King’s eyes, the son of sharecroppers who in 1958 got a prepaid bus ticket – sent by mail from Dr. King – to travel 50 miles from Troy to Montgomery and meet King.

The power of John Lewis, as he was honored on Thursday with a funeral featuring three presidents, is he remained the "Boy from Troy," incredibly humble, incredibly determined, as he put himself on the line to make American history, as he made America a better, more just nation.

Lewis had every reason to strut.

He had the right to brag about being one of the brave people in the Freedom Rides – crossing state lines on integrated buses and withstanding bloody beatings from White segregationists for breaking their racist rules.

He had every right to brag that at 23 he spoke immediately before Dr. King at the March on Washington – a speech that was a perfect prelude to “I Have a Dream,” because Lewis spoke of the harsh, violent reality facing people trying to achieve the dream of racial equality in the face of segregationist violence.

And Lewis certainly had the right to say that a week after he suffered a cracked skull – by marching for voting rights – he watched as the president of the United States, Lyndon Johnson, stood before a joint session of Congress to propose the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Imagine the Boy from Troy, having so much heart that as a 25-year-old man he was in the lead of daring activists who compelled a president from Texas to tell 70 million watching on television and the entire Congress: “Their cause must be our cause, too. Because it is not just Negroes, but it is really all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. We shall overcome.”

C.T. Vivian, a top aide to Dr. King, who died the same day as Lewis, watched President Johnson’s speech with Dr. King. In my book on the civil rights movement, “Eyes on the Prize – America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965,” I quoted Vivian as recalling that when the president said, “We shall overcome,” he looked over at King.

“Martin was very quietly sitting in the chair and a tear ran down his cheek. It was a victory like none other. It was affirmation of the moment,” Vivian said.

In today’s New York Times, in a posthumous essay by Lewis, he offered his affirmation for the continuing movement for racial justice, the Black Lives Matter movement.

At the end of a life that inspired so many, including President Johnson to take action for racial justice, Lewis praised Black, White, Latino and Asian Americans for keeping up the movement today by marching to protest today’s police brutality.

Lewis wrote today’s multi-racial movement sets “aside race, class, age, language and nationality to demand respect for human dignity… the truth is still marching on.”

The Boy from Troy wrote in the Times that as a Black child of the 1940s and 1950s he lived as a virtual captive of legal racial segregation and the racial violence used by White public officials to enforce second-class status on Black people.

More from Opinion

“Emmett Till was my George Floyd,” he wrote. “He was my Rayshard Brooks, Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor. He was 14 when he was killed, and I was only 15… I will never forget the moment it became clear that he could easily have been me.”

Lewis added that as a child his family was constrained by “an imaginary prison and troubling thoughts of potential brutality committed for no understandable reason were the bars [of that prison.].”

That child, that Boy from Troy, somehow made a way out of no way, as the gospel song says, using a steady, nonviolent passion to face down racist traditions, racist laws and violent, racist state troopers.

At a time when America offered few reasons for hope to a Black child from the rural south, that child found Godly purpose as an evangelist for racial equality.

He grew up to be Congressman Lewis. He traveled so far to be on the right side of history.

But the most amazing grace of his life is that he remained humble, available to all as a public servant, never envious of a new generation of civil rights activists, no matter their race. He was so humble as to want to pull all of America along the true path of love for all.

What a Boy from Troy.

Lewis gave me an endorsement for my last book – “What the Hell Do You Have to Lose? – Trump’s War on Civil Rights.” He wrote the book “was needed now more than ever – not just in libraries and classroom but in our homes and our hearts… we must speak up and speak out before it is too late.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

That was Lewis – in his New York Times piece, as always – inspiring us one more time.

God bless John Lewis, the man who grew from the Boy from Troy.