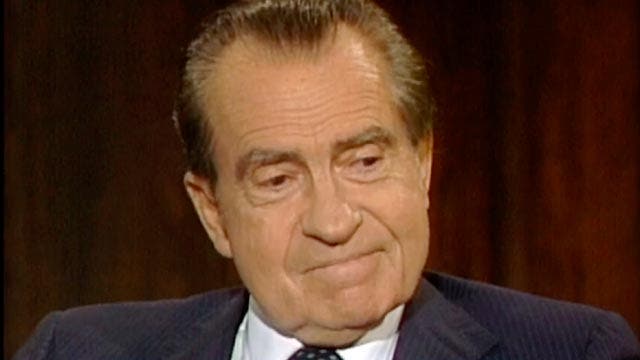

New doc paints fuller picture of Nixon

HBO's 'Nixon by Nixon' coincides with the 40th anniversary of president's resignation

Forty years ago this week, Richard Nixon became the only president of the United States to resign from office. I was a junior member of Henry Kissinger’s National Security Council staff and as close to the Watergate scandal as one could get without actually being drawn into it.

Kissinger’s staff, even those of us working in the West Wing, were isolated from the unfolding events of Watergate. No NSC staff members had been implicated, and we were preoccupied by a dazzling series of foreign policy challenges: the opening to China, rapprochement and arms control agreements with the Soviet Union, Vietnam peace accords and Middle East shuttle diplomacy following the October 1973 Arab-Israeli war.

[pullquote]

While we burned the midnight oil in Kissinger’s West Wing offices, the lights were going out in other White House offices, as one after another of Nixon’s staff resigned or was fired. Those who remained treated Watergate as the elephant in the room that no one talked about. It wasn’t just Nixon who was in trouble, but many of his most trusted aides. You didn’t know who had been subpoenaed, who had lawyered up and who was already testifying. It was hard to have a conversation, casual or otherwise, when the person you were talking to might also be talking to the Watergate special prosecutor.

Nothing was the same after the White House Praetorian guards, Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman and top domestic affairs adviser John Ehrlichman, were forced to resign in April 1973. Kissinger’s former deputy, Gen. Alexander Haig, was called back to become the new chief of staff. Other than that, departing aides were rarely replaced, and their offices remained empty, lights out. The West Wing became a ghost town.

Even so, I, along with an ever-dwindling number of my NSC colleagues, held out hope that Nixon would be found innocent of charges he had lied to the American people, and that his administration could weather the storm. But once the Supreme Court ordered the release of the president’s secret Oval Office tapes on July 24, 1974, the proof was there. While Nixon may not have ordered the break-in of the Democratic National Committee’s Watergate offices, the tapes showed he was part of the elaborate efforts to cover it up from the very beginning. The question of the day – “What did the president know and when did he know it?” – would soon be answered.

On Monday morning, Aug. 5, I came through the West Basement entrance to see several staffers huddled around the guard’s desk, reading Xeroxed papers. The White House had just released three transcripts of Nixon’s tapes, plus a presidential statement. The “smoking gun” tape was the evidence Congress had been waiting for. Nixon would be impeached within days and, in all likelihood, tried and found guilty. It was either that or resign.

There was nothing more to say. The Nixon presidency was drawing to a close within days, hours or weeks, and Vice President Gerald Ford would soon become president. Our job was to get him ready, but without seeming to do so, since Nixon had not made any final decisions. The vice president and his staff had almost no dealings with the rest of the White House staff. Ford rightly decided it would be improper to prepare for the presidency before Nixon resigned, and it would be improper to urge Nixon to stay. So he, and his staff, remained silent and apart.

But the United States was in a period of intense and confidential negotiations with several foreign governments that the new president would need to take over within hours of being sworn in. Most new presidents have over two months between election and inauguration to become familiar with the state of America’s ongoing foreign relationships. Gerald Ford had less than four days.

We got word early Thursday, Aug. 8, that Nixon would address the nation that evening to announce his resignation the following day.

We all came to the White House early on Aug. 9, and we were fast at work preparing materials for Kissinger to brief the new president. My colleagues and I left our West Wing offices and walked to the East Room at about 8.15 a.m. The Cabinet and senior White House officials were sitting in hastily assembled chairs; the junior staffers were lined up along the wall. I stood next to a window overlooking the south lawn. Everyone was either crying or stone, cold quiet.

At 9 o’clock the Nixon family walked into the East Room and stood with the president at the podium. When Richard Nixon walked into the East Room, he was the most powerful man in the world; when he left, he was just Richard Nixon and his family. I remember thinking that no matter how high you rise, you had best be at peace with yourself and your family, because in the end, that is all you will have.

When Nixon finished his remarks, he and his family walked through crowds in the East Room to the portico, then walked down the staircase with Vice President and Mrs. Ford to the helicopter waiting on the south lawn. We followed the Nixons and Fords onto the lawn, and silently waved goodbye.

I headed back to the West Wing for more paperwork, and then two hours later returned to the East Room for President Ford’s swearing in. Back again were the Cabinet and White House staff, now joined by senior members of Congress and their spouses. Ford took the presidential oath to enormous applause and declared that our “long national nightmare” was over. He asked the nation to pray for him, and for the former president and his family. He hoped that Nixon, who brought peace to millions, could find peace for himself.

For the first time in over a hundred years, a president had faced impeachment, and for the first time in American history, a president had resigned. At the time, it seemed like Richard Nixon had committed an unforgiveable crime, an abuse of power so serious, so grievous, it demanded he leave office.

It’s laughable to look at the events of 40 years ago through today’s eyes. A president who lies to the American people? They do it all the time nowadays – from Clinton’s “I never had sex with that woman” to “If you like your health care plan you can keep it.”

An administration that covers up its crimes? Lois Lerner’s lost IRS emails and crashed hard drives make the missing 18-minute gap on Nixon’s tapes look puny. Nixon wiretapped a handful of reporters and officials to track down leaks of highly classified military information about the Vietnam War, but that was nothing compared to the CIA tapping into the computers of congressional staff or launching criminal investigations of reporters who write stories critical of them.

Nixon fired a special prosecutor who wouldn’t do his bidding; Obama won’t even appoint one.

What has happened in the last 40 years is that we’ve grown immune to the abuse of power. The outrage that fueled the Watergate era is gone; we’ve become so used to corrupt politicians, we hardly raise an eyebrow.

Where is the outrage from the media when the administration taps their phones and reads their emails? Or from Congress when the executive branch spies on it and lies about it? Or from the Judiciary when the president enforces those laws he likes and ignores those he doesn’t? Or from the American people when the president’s aides persecute average citizens whose political beliefs run contrary to theirs?

This week the Nixon Foundation posted videos of interviews Nixon gave to an aide 10 years after Watergate. The media always portrayed Nixon as evil, conniving and with a sinister 5 o’clock shadow. Cartoons showed him as a hunchback, bent over and rubbing his hands together – looking like the embodiment of Shakespeare’s murderous Richard III.

But the Nixon in these newly released videos show a man who is humbled and has come to terms with his mistakes and failures, yet remains justifiably proud of his accomplishments in foreign and domestic policy. When asked why he chose to resign rather than stand trial in the Senate, Nixon said he was always a fighter and that he had wanted to fight impeachment, even if it ended with the Senate removing him from office. But he resigned because he didn’t want to put the country through a constitutional crisis of a prolonged impeachment. How many of our modern politicians would put the country first, before their political careers?

People are still debating the significance of the Watergate scandal. Some say it was proof that, in America, no one is above the law, and the system worked. Others say Nixon, despite his many accomplishments, was hounded out of office by a powerful and hostile press corps who never liked him. It is probably some of both.

But the lasting legacy of Watergate, and its companion piece, the Vietnam War, is that it began an era of eroding trust in Washington, in our institutions of government and especially in our political leaders.

The legacy is that the majority of our modern presidents have dealt with scandal and special prosecutors ever since.

Opinion polls consistently show that confidence in government is lower today than at any time since polling began. The great majority of Americans think the country is headed in the wrong direction, and they disapprove of the current president’s handling of foreign and domestic affairs. His low approval ratings are surpassed only by the even lower approval ratings of Congress. President Obama was elected in part because he wasn’t President Bush, who was elected in part because he wasn’t President Clinton. We no longer vote, if we vote at all, for the candidate we like; we vote for the one we dislike least. It’s contagious. Not only do we no longer trust our government, we increasingly no longer trust each other.

Who knows where this leads? Some say if we only had better leaders in Congress and the White House, all these problems would evaporate and people would believe in government again. I’m not so sure.

That’s the lasting legacy of Watergate. And that’s the greatest tragedy of all.