Brandon Phillips as a young boy getting ready for Christmas. (Courtesy of the author)

I was born with a congenital heart defect (CHD) in the late 70s. During one of my visits with my pediatric cardiologist, my mother mustered enough courage to ask how long I would live. He replied that his oldest patient with my condition was in his 20s.

I must have fixated on this number without realizing it, only seeing my life for that far into the future. Over the years, my pediatric cardiologist would occasionally mention medical advances and research studies. I knew they were still learning how best to treat patients based on those who came before me. But even as a first-year medical student, the reality of living long enough to have a future as a practicing physician had not yet set in.

An early picture of Brandon with his maternal grandparents. (Courtesy of the author)

Brandon with his family. (Courtesy of the author)

The open-heart surgery I had as a young child was “successful,” but I was left with an incompetent pulmonary valve – with each heartbeat some blood intended to reach my lungs would slosh back into my heart. My heart had to work harder, and my heart enlarged and became less effective over time.

During medical school, it was recommended that I get an artificial valve to replace my incompetent one, and this open-heart surgery was also a success. Even though I didn’t feel tired before, I noticed an increase in energy after my surgery. It seems I had adapted my lifestyle to my limitations.

At the beginning of medical school. (Courtesy of the author)

I ultimately became a pediatric cardiologist, inspired by and learning my craft from the very physicians who had cared for me. During my training, I realized that people with CHDs were living longer with more options and opportunities than I ever imagined. I thoroughly enjoy treating children, seeing myself in many of those I now care for.

Heart defects are the most common type of structural birth defect and occur in 1 out of every 125 births. CHDs are classified into about 35 different types with many variations and differences in severity for each type. Some defects are minor and resolve on their own in time while others require urgent surgery. Treatment is individualized based on the patient’s unique heart, and the need for lifelong care is not uncommon. One of the greatest advances in medicine is that there are now more adults living with CHDs than children living with these health challenges, something we could not say 20 years ago.

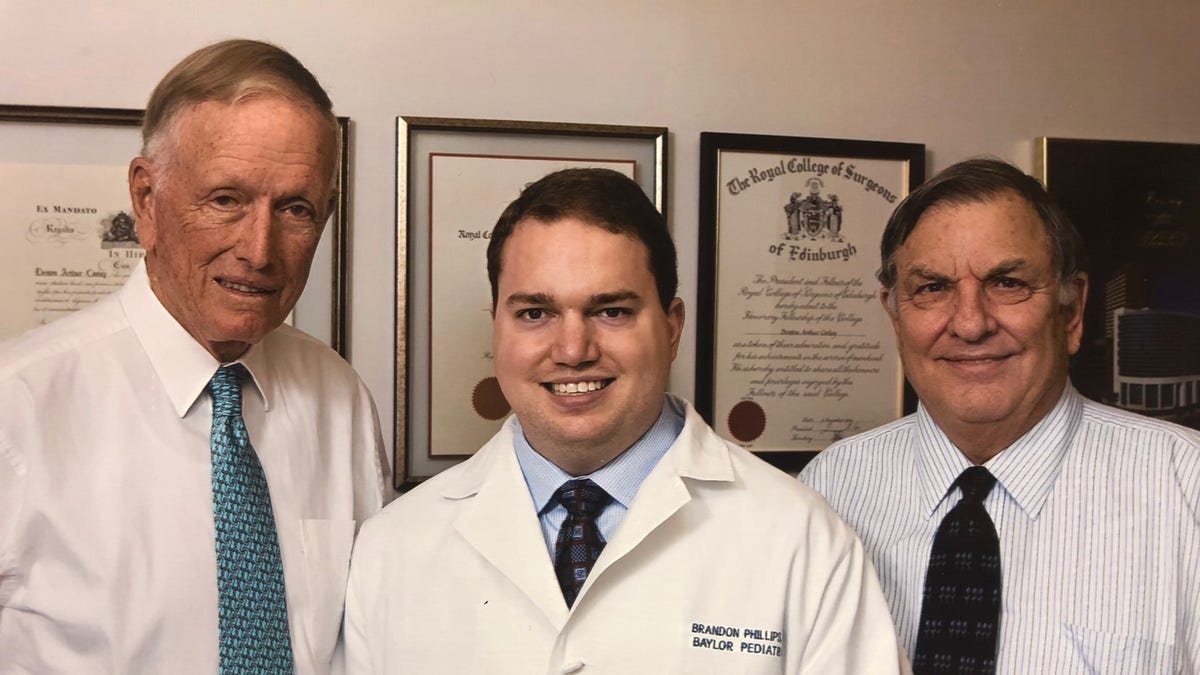

Taken during Brandon's residency at Texas Children’s Hospital with his heart surgeon (Dr. Denton Cooley) and pediatric cardiologist (Dr. Tom Vargo). (Courtesy of the author)

The registered nurse who works with me in clinic is also a CHD survivor. Previously, she worked in the neonatal intensive care unit, and we met while I was making rounds one day. The family she was caring for was overwhelmed by the prospect of taking home a child with a heart defect. She asked me to reassure them, sharing her story of survival with me. We were surprised to learn we both had been repaired by the same surgeon. Together, we let this family know that kids facing heart defects can survive and thrive!

Even into adulthood, additional procedures may be needed, and sometimes new technologies allow for more treatment options. In my case, it was after 15 years of dedicated service that I could hear my replacement heart valve leaking with my own stethoscope. I knew it had become incompetent and needed to be replaced. But this time around, open-heart surgery was not required thanks to continued medical advances. My new valve was guided into position through the blood vessels leading to my heart in an interventional cardiology procedure. Of course, I asked to borrow a stethoscope in recovery, so I could assess my new valve for myself. And unlike previous surgeries requiring a lengthy hospital stay, I was discharged the following day.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

I have the privilege of working with Dr. Terry King, a pioneer in pediatric cardiology. In 1974, he and Dr. Noel Mills invented the cardiac umbrella device to close holes between the top chambers of the heart without needing open-heart surgery. Millions worldwide have now had variations of this procedure, and it led to further advances in the field, including the valve I recently received. A decade ago, I couldn’t have imagined such technology would be possible, and it makes me hopeful for what the future may hold for myself, for others with CHDs, and for my patients.

During this week, as we pause to focus awareness on congenital heart defects, it is important that we acknowledge those who have and continue to work so diligently toward better treatments and even cures for these defects. It is because of them, that not only I but countless others like me, have futures that are wide open to us. It is so important that we support ongoing research and encourage continued growth, so those with CHDs can be excited about planning a long and full future.