Explosions on Mont-Blanc (NSA)

Dec. 6, 1917 – exactly 100 years ago – marks one of the most extraordinary episodes of American heroism, when common U.S. citizens rushed to the scene of a disaster unlike anything the world had seen before.

A French freighter carrying 6 million pounds of high explosives intended for the trenches of the World War I blew up in Halifax, Nova Scotia, wiping out half the Canadian city, wounding 9,000, and killing 2,000 more. It was the world’s biggest man-made explosion until America dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945.

Within an hour of the explosion in Halifax, the people of Boston starting sending two trains and two ships with 100 doctors, 300 nurses and $1 million in medical supplies – all without being asked.

The Americans’ remarkable compassion and courage helped transform Canada from an adversary to an ally, and is honored every winter when Nova Scotia spend $180,000 to send the province’s biggest and best Christmas tree to Boston Common in gratitude for helping to save their city a century ago.

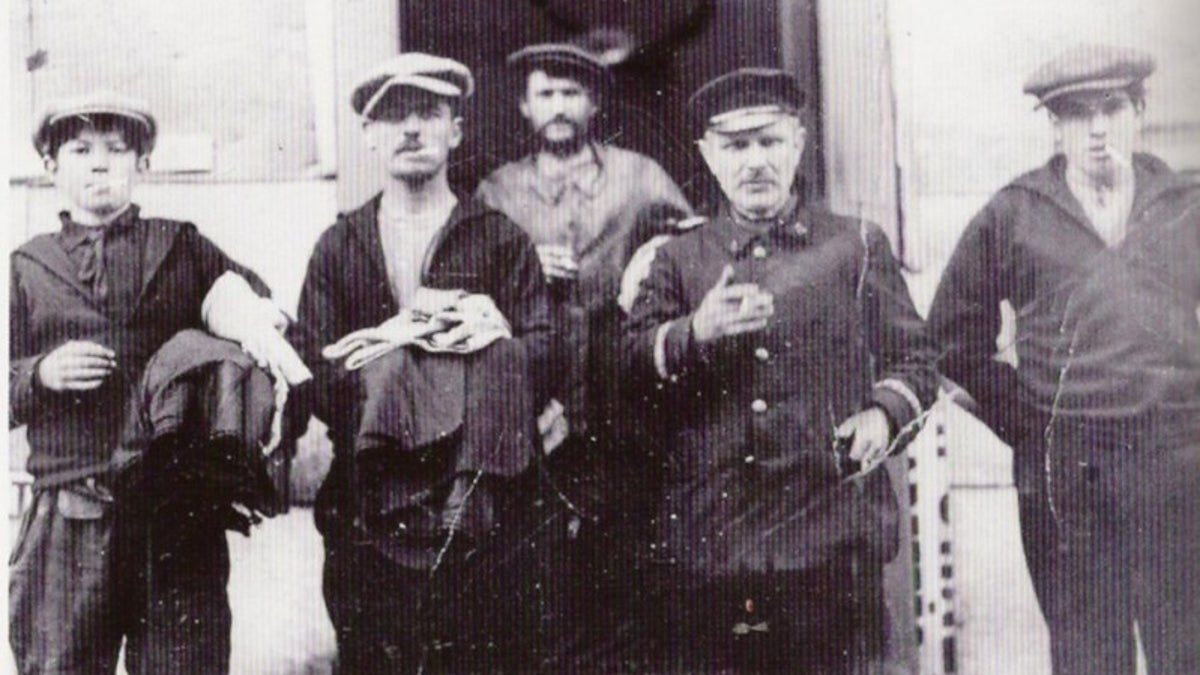

On the morning of disaster, the captain and crew of a French munitions ship called Mont-Blanc were eager to reach the safety of Halifax Harbor – and with good reason.

Mont-Blanc Crewmen (MMA)

Five days earlier a crew of stevedores in Brooklyn in New York City had finished loading the ship with a staggering 6 million pounds of high-explosives – 13 times the weight of the Statue of Liberty. The touchy cargo was headed for France, where it was to be packed in shells and fired on Germans to break the Great War’s three-year stalemate.

A Norwegian relief ship named Imo was just as eager to go in the opposite direction to New York to get supplies. At Halifax Harbor’s narrowest stretch, the Imo passed several ships on the left, against nautical convention, which set it on a collision course with Mont Blanc, hugging the shore.

In this high-stakes game of chicken, Mont-Blanc bailed first, pivoting to the left at the last second – also against nautical convention. This would have worked – if Imo hadn’t steered to the center at the exact same moment.

At 8:46 a.m. Imo struck Mont-Blanc’s bow, igniting barrels of airplane fuel on deck. Mont-Blanc’s crew escaped on lifeboats, while Halifax’s workers and schoolchildren watched the ghost ship slip perfectly into Pier 6.

At 9:04 a.m. Mont-Blanc erupted, leveling almost half of Halifax, rendering 25,000 people homeless, wounding 9,000, and killing 2,000 more – all in less time than it takes to blink.

Years later, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the architect of the atomic bomb, correctly calculated the bomb dropped on Hiroshima would be only five times more powerful.

At 10:13 a.m., Boston’s leaders received a brief telegram about the tragedy. It was hard to predict how they would respond.

On the one hand, the Revolutionary War pushed some 30,000 Loyalists to the British from New England to Nova Scotia with hard feelings.

During the War of 1812, one of Nova Scotia’s favorite sons, Joseph Barss Jr., returned the favor by capturing, sinking, or burning more than 60 American ships. This made him the most wanted man in New England.

During the Civil War, people in Halifax helped a notorious Confederate battleship, the Tallahassee, sneak past Union ships under cover of darkness.

For the Americans’ part, when the U.S. speaker of the House took the floor of Congress in 1911 to advocate annexing Canada, Massachusetts’s representatives didn’t raise a peep.

But Boston and Halifax were two shipping towns that had more in common than most. Boston was home to thousands of Halifax cousins and transplants, including James Earnest McLaughlin, who designed Boston’s Fenway Park.

It was helpful that in April 1917, the United States finally entered the Great War, becoming allies with Canada for the first time. Plus, Boston had just created something no one else had – a Committee on Public Safety, for disasters like this.

About two hours after the explosion, Massachusetts Gov. Samuel W. McCall sent a telegram to the mayor of Halifax: “Understand your city in danger from explosion and conflagration. Reports only fragmentary. Massachusetts ready to go the limit in rendering every assistance you may be in need of. Wire me immediately.”

Boston Doctors (NSA)

While waiting for a response, McCall gathered the Committee on Public Safety at Faneuil Hall, where 100 leaders formed the Massachusetts-Halifax Relief Committee and organized a relief train to leave that evening.

When Gov. McCall’s second telegram to Halifax received no response, he sent a third: “Realizing time is of the utmost importance we have not waited for your answer but have dispatched the train.”

Explosion survivor and Halifax historian Thomas Raddall recalled: “Doctors and nurses arrived from outlying provincial towns and substantial help was on the way from Montreal and Toronto, but the first and most valuable assistance came from the ancient foe beyond the Bay of Fundy.” Boston.

The Boston train had to smash through gigantic snowdrifts left by the Maritimes’ biggest blizzard in a decade.

Blizzard Day After Explosion (MMA)

When McCall’s representative arrived Saturday morning, he handed a Canadian official the governor’s letter, which assured him: “I need hardly say to you that we have the strongest affection for the people of your city, and that we are anxious to do everything possible for their assistance at this time.”

The stoic official could not hide the tears streaming down his face. “Just like the people of good old Massachusetts,” he said.

McCall’s group sent another train and two ships loaded with food, clothing, bedding, motor trucks, medical supplies, welfare workers, 300 nurses and 100 doctors. The group included Dr. William E. Ladd, whose experience in Halifax would help him become the “father of pediatric surgery” back in Boston.

When Boston newspapers told their readers where the next relief ship had docked, the pier overflowed with Good Samaritans eager to contribute to the cause, including a “society lady” who doffed her fur coat and added it to the cargo.

When the ship pushed off from the pier, one reporter said “a lusty cheer went up from the crowd of workers and spectators who lined the docks.”

Halifax greeted Boston’s help “with a gasp of relief,” Raddall wrote. “And this was only the beginning. Financed entirely by American funds, the Massachusetts Relief Commission continued its clinics and its housing and welfare work in Halifax long after the disaster, a memory cherished by Haligonians to this day.”

Some seven decades later, interviewer Janet Kitz noticed the first thing aging survivors mentioned was the “instant and unstinting aid from the State of Massachusetts.”

Joseph Ernest Barss, the great-grandson of Canada’s deadliest privateer, had been wounded in the Great War and returned to Nova Scotia to recover. When the Mont-Blanc exploded, he put his first-aid experience to use for three sleepless days before being relieved by medics from Boston.

“I tell you we’ll never be able to say enough about the wonderful help the States have sent,” Barss wrote his uncle. “The response was so spontaneous and everything done even before it was asked for. It brought tears to all our eyes. You know we have always been a trifle contemptuous of the U.S. on account of their prolonged delay in entering the war. But never again! They can have anything I’ve got. And I don’t think I feel any differently from anyone down here either.”

In the 1920s, Canada opened official diplomatic relations with the United States, and has been our nation’s biggest trading partner for decades – exceeding China, Japan, Germany and Mexico.

On Nov. 30, the people of Boston lit the Christmas tree, a testament to a time when the worst the world could inflict brought out the best in two countries. The hard-earned friendship those days forged has stood as an example to the world for a century.

“Why,” one Nova Scotian asked, “do we have to stop saying ‘Thank you!’?”

Adapted from John U. Bacon’s latest book, "The Great Halifax Explosion: A World War I Story of Treachery, Tragedy, and Extraordinary Heroism."