Not all scandals are alike, and nowhere is that more true than in the case of recent events at the General Services Administration and the Secret Service. Don’t get me wrong, neither story is anything to be proud of, but even if the worst is confirmed regarding the behavior of 11 Secret Service personnel in Cartagena, the scenarios are fundamentally different and the GSA story is far worse.

To be sure, the agents who are suspected of bringing prostitutes to their hotel rooms clearly violated what Secret Service Assistant Director Paul S. Morrissey described as the service’s “zero-tolerance policy on personal misconduct.” And while I am no prude, and would never reduce my assessment of another person based on their decision to avail themselves of a prostitute, prostitution is not a victimless crime, and by supporting it, the agents involved supported a harmful practice, whether they intended to do so, or not.

So far, as this story unfolds, the agents appear not to have broken any laws.

We don't know all the facts here yet and we are also still left with a list of “what ifs”:

- Did the agents open themselves up to the possibility of being blackmailed? Right now, we do not have evidence that the women involved in the case, now perhaps as many as 21 of them, were foreign agents interested in obtaining otherwise secret information from the agents involved.

- Did the agents use tax-payer money to pay the prostitutes whom they are accused of bringing to the hotel?

Despite all these questions, I am convinced that the agents involved betrayed the public image of the Secret Service, and to a lesser extent, that of the nation. Unlike employees at the GSA, however, they did not betray the public trust. And that's a crucial difference.

Of course, should it emerge that any one of the possibilities just mentioned actually did occur, then we would have to move the agents’ behavior from the betrayal of image “column” to the betrayal of trust “column”, where the indiscretions at the GSA firmly stand.

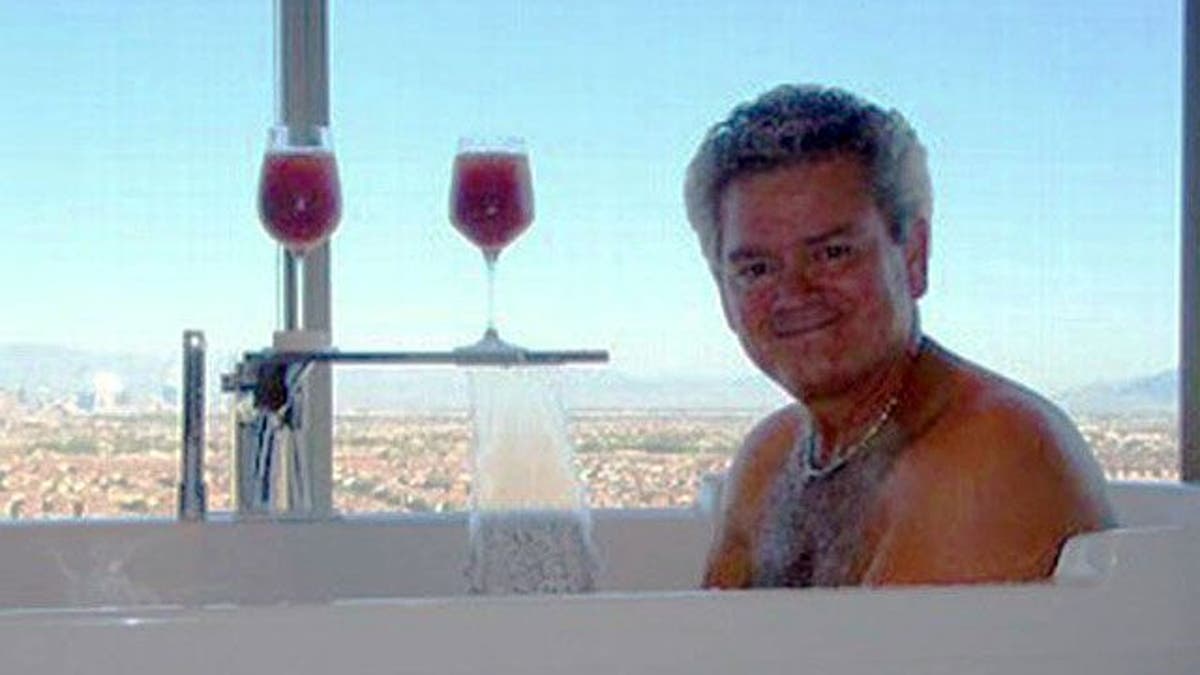

Spending over $823,000 for a few days in Las Vegas, even for 300 people, as GSA did, is simply nuts.

Let’s do the math. -- That comes out to almost $3,000 dollars a head, in a city where they are practically giving away hotel rooms because the local economy is so bad! But it is not only crazy, it is offensive.

And that’s just the beginning. Not only was this a case of financial mismanagement, it was a case of brazenly spending other people’s money – yours and mine – because those who did so had no regard for the finances of those they serve – you and me.

Yes, those are strong words, and I would hesitate to use them if the Las Vegas event had been an isolated incident. In fact, no organization is immune from mistakes and occasional over-indulgence. But in the case of the GSA, it’s systematic.

It extends to spending $330,000 dollars to relocate a single employee to Hawaii, and authorizing multiple staff members to spend 7 days in those same islands in order to attend a one-hour ceremony. And those are just a few examples from among the many which have surfaced recently, let alone those that surely will.

The issue at GSA is not simply, as some are suggesting, about the need for competitive bidding or tougher spending guidelines. That would simply add more bureaucracy to fight the current one. That may actually be necessary, in the short term at least, but that is not the real issue here.

The issue here is trust, especially at time when trust in the government’s ability to use citizen’s money wisely is at or near an all time low.

When government officials fail to act as good stewards of the nation’s dollars, they are not only wasting money, they betray the trust of the American public. And once betrayed, trust is a very difficult thing to reestablish. Restoring trust in the GSA will certainly require more than a few firings and demotions. --And it’s not likely to be reestablished through lengthy, costly, and likely politically charged hearings in Congress either.

Of course, the GSA scandal is actually both a challenge and opportunity. The challenge lies in seeing the full dimensions of the problem which the agency’s abusive spending represents, the fact that people are responding so sharply because of the broad scale loss of faith in government agencies to accomplish even those tasks which most Americans support, and in responding more intelligently than we typically do at these moments.

The opportunity lies in people being willing to ask not simply how to preserve or kill any particular program, initiative or agency, but in assuring that public employees see themselves as stewards of the public trust.

We must insist that the first question asked in any government agency is: are we providing the greatest possible value to the American people, and doing so in a way which builds their confidence in our ability to do so?

Arguments about big government vs. small government will come and go, but wherever you come down on that issue, that is the real question that must be asked by both sides, each and every day, in order to build trust in government, no matter how big or how small.

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield is the author of "You Don’t Have to Be Wrong for Me to Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism," and president of Clal-The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership.