Let me say this right at the top: I was scared of my grandfather.

Hollywood tends to portray grandparents in something of a golden glow, and understandably so.

After all, who isn’t drawn to warm and friendly seasoned citizens?

DEROY MURDOCK: AND THE OSCAR FOR WORST IDEA FOR MOTION PICTURES GOES TO ...

That stereotype may have fit my grandparents on my mother’s side, but it wasn’t my grandpa from my dad’s. William “Will” Batura was a short, stout, grumbly and grouchy man with an artist’s flair who made his living painting the insides of New York City’s early skyscrapers.

Serene and sage, gregarious and generous, loving grandmas and grandpas are usually depicted as bespectacled and big-hearted, if even a bit eccentric.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

Think Jack Albertson as “Grandpa Joe” in the original (and best) “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,” Will Geer on “The Waltons” or Peter Falk (“As you wish”) in “The Princess Bride.”

Then there was Grandpa Munster, played by the wild-eyed Al Lewis. Vladimir Dracula, the Count of Transylvania on the zany “Munsters” ‘60s sitcom, was supposed to be pushing almost 600 years of age, so some of his oddities could be expected and excused.

More from Opinion

But on this National Grandparent’s Day, with over 70 million grandmas and grandpas in America, I’m thinking of Will Batura, a very imperfect man who was born in 1890 to Polish immigrants.

By the time I came around in 1972, my grandfather was widowed and pretty much confined to his living room chair, where he sat and read or invited us to watch old Abbott and Costello movies with him on Sunday afternoons. He was never without a lit cigar, which he puffed incessantly.

To this day, whenever I smell a stogie, I think of my grandfather. I love their aroma. It’s shocking to me that despite his bad habit, he lived till 87.

"Will Batura, a very imperfect man who was born in 1890 to Polish immigrants." (Family photo)

I’m reminded of George Burns’ famous quip, “If I had taken my doctor’s advice and quit smoking when he advised me to, I wouldn’t have lived to go to his funeral.”

In his old age, my grandfather was the nervous type. He was convinced my siblings and I were going to destroy his small, saltbox house at 309 S. Broome St. in Lindenhurst on Long Island. If we wandered away from the couch to the kitchen, he would holler after us.

Looking back at my grandfather, I’m reminded life’s best lessons don’t come from watching perfect people do everything well.

“What are you doing in there?” he would grouse. “Nothing,” I would reply. Truth be told, I was usually stealing M&M’s that he kept in a big glass jar.

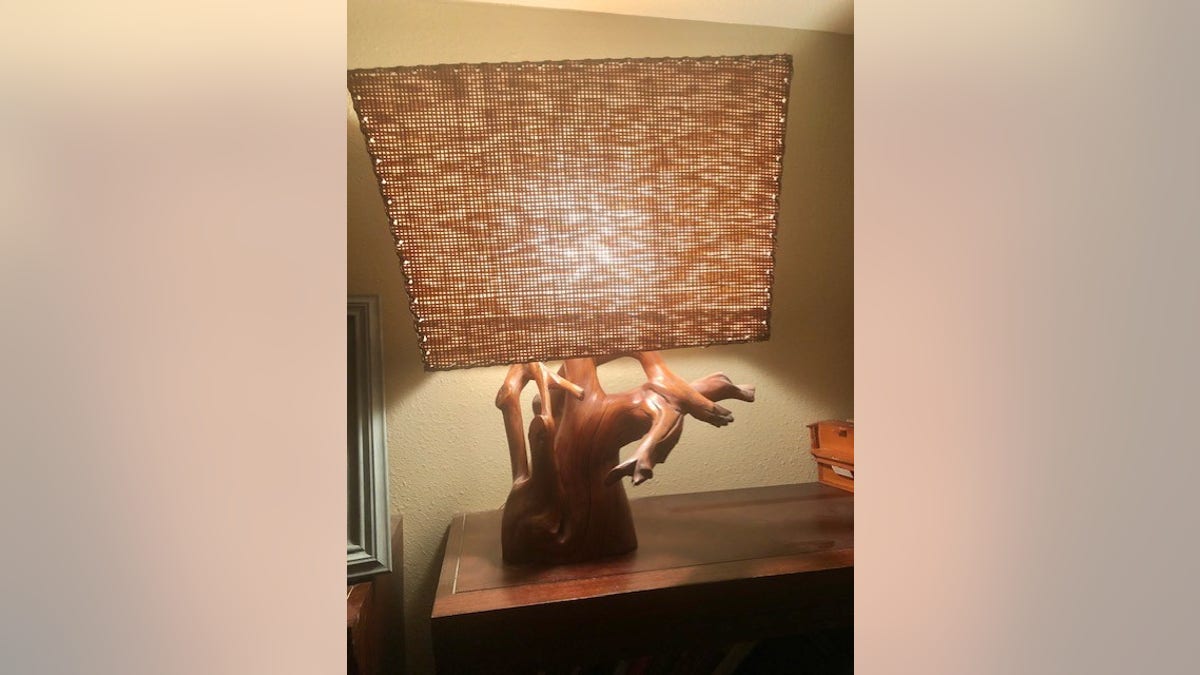

My older siblings remember doing projects with my grandfather, building birdhouses with scrap wood, in particular. He said he loved creating homes for innocent, vulnerable creatures. A master craftsman with chests of ancient tools, he built all kinds of things, including lamps made from reclaimed driftwood.

In fact, I’m writing this in the soft glow of the light of one of those very lamps. Another wooden box he built is to my left, full of treasured cards and letters from my life.

"A master craftsman with chests of ancient tools, he built all kinds of things, including lamps made from reclaimed driftwood." (Family photo)

My own father often butted heads with my grandpa, but said he learned a lot about being a husband and dad from him – that is, by often acting or behaving in a contrarian manner.

Where my grandfather was gruff, my dad was gentle. Where he was domineering and demanding with his wife, my father went the extra mile to serve my mom. My grandpa jumped from job to job. My dad worked for one company for 44 years.

Looking back at my grandfather, I’m reminded life’s best lessons don’t come from watching perfect people do everything well. Some of the most profound teaching comes from recognizing our own or other people’s mistakes and shortcomings.

Imperfections and all, I loved my grandfather – and I always knew he loved me. He’d wrap his big, burly hands around my small ones and give me warm hugs as we arrived or departed. “Be a good kid and make us proud,” he’d say in a thick, Brooklyn accent, slapping my cheek for extra emphasis.

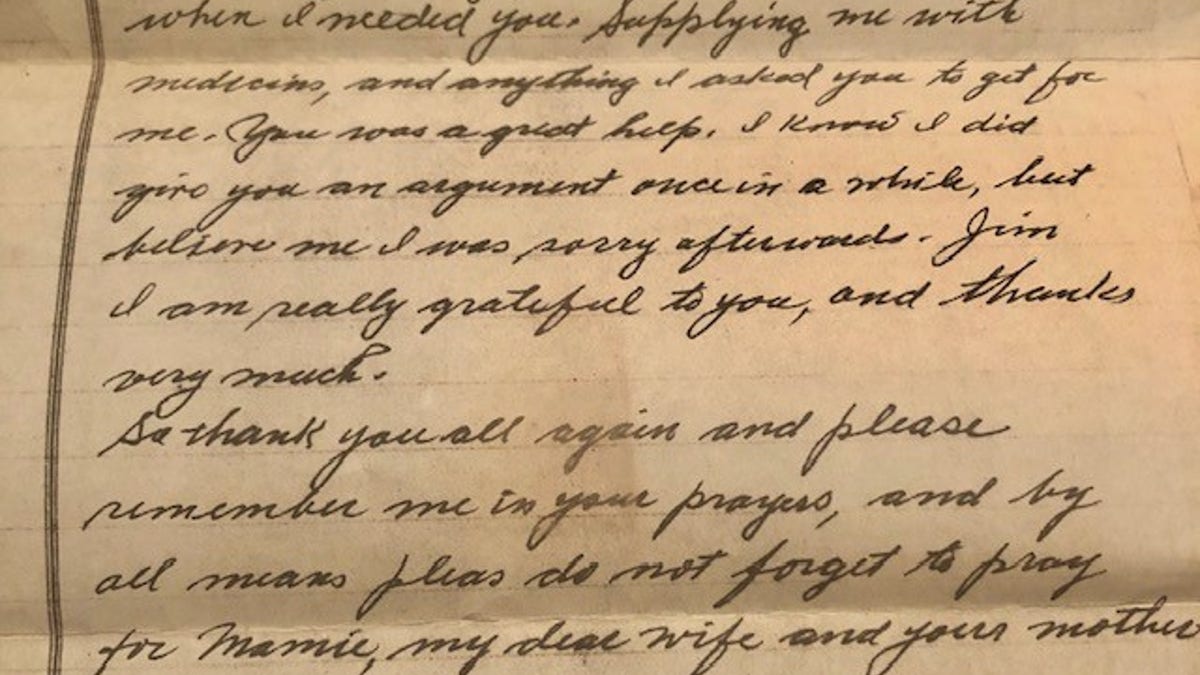

I’m told my grandpa softened and mellowed with time, something that seems evident thanks to a letter my dad found in my grandfather’s handwriting beside his chair the night he died.

“And you Jimmy [my dad] you were always there when I needed you,” he wrote. “Supplying me with medicine, and anything I asked you to get for me. You were a great help. I know I did give you an argument once in a while, but believe me I was sorry afterward. Jim I am really grateful to you, and thank you very much.”

"My dad said he wept when he found the note ..." (Family photo)

My dad said he wept when he found the note, which he read over and over while sitting in my grandfather’s chair. When my own dad died, I found that 40-year-old note in a table beside his easy chair.

It’s not lost on me that my grandpa built small masterpieces with old and discarded materials, giving new life to the marred and imperfect. He knew that everything and everyone is redeemable – because he had been a work in progress himself.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Grandparents are one of God’s greatest gifts. But they’re not perfect. Nobody is. If you are one, though, don’t underestimate the impact you can have on the next generation.

If you have one, cherish the relationship – it goes all too quickly. If you’ve lost one or all of them, like me, don’t just mourn their passing, but be grateful for the time you’ve enjoyed in their company.