'Thomas Jefferson' reads from Declaration of Independence

Anna Kooiman talks with the Founding Father in Colonial Williamsburg.

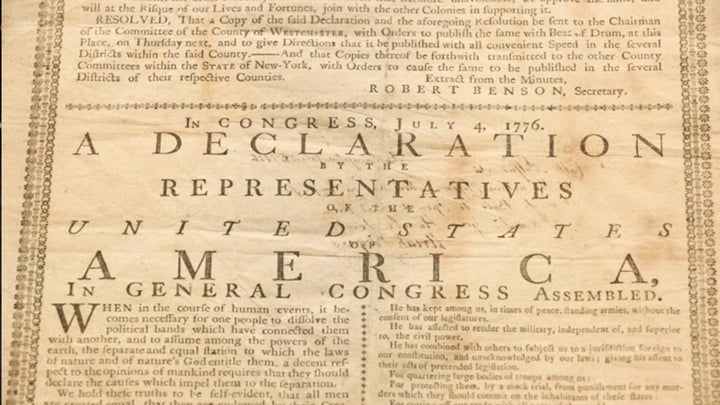

When Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence two hundred and forty-five years ago, he put the British crown and the rest of the world on notice. Yet, it might surprise some that one of the document’s most ardent and consequential champions would be a Frenchman.

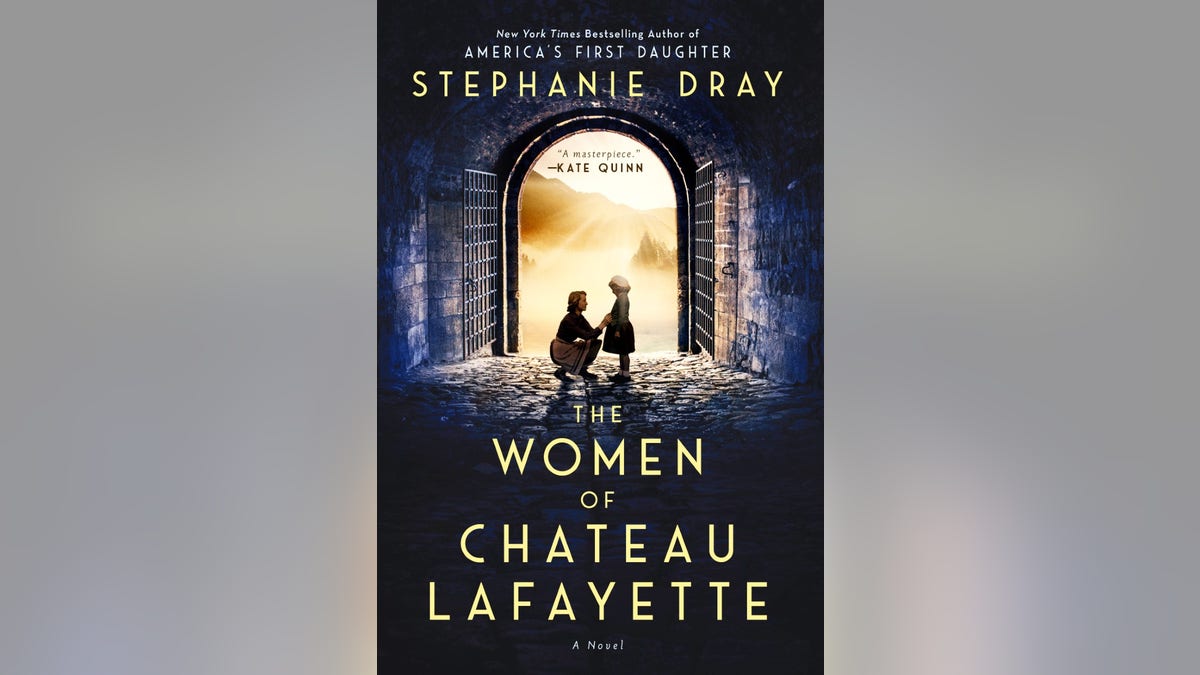

As I explore in my new novel, "The Women of Chateau Lafayette" (Berkley Books, March 2021), Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, surrendered his noble title in solidarity with the idea that all men are created equal and left behind a world-changing American legacy that has played out generation after generation.

At the tender age of 19 , Lafayette wrote, "The moment I heard of America, I loved her; the moment I knew she was fighting for liberty, I burnt with a desire to bleed for her."

A statue honoring Lafayette in Paris, France.

He did just that at the Battle of the Brandywine, having crossed an ocean against the wishes of his French king to fight in the American cause. And despite his youth, he would go on to become one of George Washington’s most trusted aides and friends.

FOURTH OF JULY: WHY DO WE CELEBRATE WITH FIREWORKS?

Together they secured American victory both by facilitating a much-needed alliance with France, and by trapping Cornwallis at Yorktown, where a decisive American victory effectively ended the war. It’s no wonder that Jefferson once remarked that, in securing America’s rightful place "among the powers of the earth," he had only "held the nail" whereas Lafayette actually "drove it."

But Lafayette’s belief in, and service to, the founding principles of the nation didn’t end at Yorktown. He carried them back to France, where he displayed a copy of the Declaration of Independence in a double frame--one side empty and waiting, he said, for the French version.

WHITE HOUSE ANNOUNCES PLANS FOR FOURTH OF JULY CELEBRATIONS

"The happiness of America is intimately connected with the happiness of all mankind," he told his wife. Lafayette insisted the human rights articulated in the Declaration of Independence were universal and America made herself an example for a more enlightened world. Lafayette’s "Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen" touched off both the French and Haitian revolutions, and still carries constitutional force in French law today.

His fight for freedom was not without consequence. Lafayette languished for five years in a dungeon and lost family to the guillotine. But not even these horrors shook his faith in the American experiment, which he returned to celebrate as the Guest of the Nation in 1824.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

It was on this visit that America’s adopted son was forced to reckon with the Declaration’s ideals versus the Constitution’s pledge to build "a more perfect union." Lafayette was appalled by the lack of progress that had been made in ending slavery in the United States; he was not shy about saying so to Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and President James Monroe. Lafayette, having been invited to help Americans heal their divisions, made a point of visiting the African Free School in New York and shaking the hands of Black veterans.

Portrait of Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert Motier (1757-1834), Marquis of Lafayette, French general, politician, engraving by Hopwood from Histoire de la Revolution Francaise (History of French Revolution), volume I, by Adolphe Thiers, published by Furne, Jouvet et Compagnie, Paris, 1880. (Photo by Icas94 / De Agostini via Getty Images) (Photo by Icas94 / De Agostini via Getty Images)

"I would never have drawn my sword in the cause of America, if I could have conceived that thereby I was founding a land of slavery," Lafayette reportedly said, though this quote was attributed to him long after his death. Whether apocryphal or not, in the end, he did not conceive of having founded a land of slavery. Rather, Lafayette was a true abolitionist who advocated both emancipation and racial equality, believing the United States would ultimately live up to its promise. "I shall probably not live to witness the vast changes in the condition of man, which are about to take place in the world," he said. "But the era is already commenced, its progress is apparent, its end is certain."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

In short, he had faith in the spirit of 1776 and America’s capacity to change and grow. It was a faith that was answered during World War One, when the United States embraced her destiny as a world power and helped end the bloodshed in Europe with the words, "Lafayette, We Are Here." A faith again gratified when, during World War Two, America threw her might behind the field of western democracies she had sown.

America has often fallen short of its founding document’s ideals. But if we resurrect our Frenchman Founding Father’s example, we can rediscover all that is great about America.