The 'great disconnect' of Barack Obama

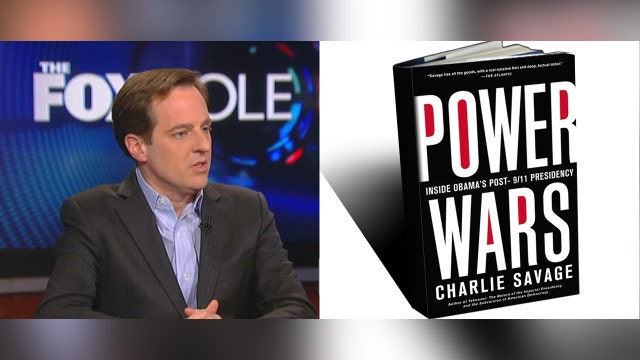

Fox News Chief Washington Correspondent James Rosen talks to author Charlie Savage about his book,

At the White House Correspondents Association Dinner in 2011, an annual black-tie ritual for 2,000 Beltway reporters and other insiders, “SNL” comedian Seth Meyers roasted President Obama with jokes on a broad array of soft targets: from the 2,600 pages of Obamacare legislation (“longer than The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo”), the national debt (“when my speech started [America] was still a nation that was rated AAA by Standard & Poors”), and the toll the presidency had taken on Mr. Obama’s appearance, as it does on all occupants of the Oval Office (“When you were sworn in, you looked like the guy from the Old Spice commercials; now you look like Louis Gossett, Sr.”).

But one riff stood out. Surveying the emerging crop of Republican presidential candidates for the 2012 contest, Meyers conceded “it’s not a strong field,” and suggested – prophetically, as it turned out – that it was unlikely to produce a general election candidate who could defeat the president in his bid for re-election. Then came the twist of the comedic knife. “I tell you who could definitely beat you, Mr. President,” Meyers said, turning to his prey, seated on the dais. “2008 Barack Obama. You would have loved him! So charismatic; so charming. Was he a little too idealistic? Maybe. But you would have loved him.”

Meyers’s joke cut to the core of what will surely emerge as an enduring question about the Obama presidency long after its terminus in January 2017, to wit: Did Barack Obama betray his campaign promises? Put differently: Should liberals, who held such great hope for Mr. Obama as a transformative president – particularly in the realm of national security, following the Bush-Cheney years, and the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, from which Candidate Obama promised to extract us – be disappointed by the president’s ultimate performance in office?

Freshly arrived with heaping volumes of information to help voters – and historians – decide that question is Charlie Savage, the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the New York Times and author of Power Wars: Inside Obama’s Post-9/11 Presidency (Little, Brown, November).

At 769 pages – an index for the book appears online, at www.charliesavage.com/powerwarsindex – Power Wars marks a monumental contribution to the literature of the Obama presidency, carefully researched and comprehensive in scope. For the project, Savage interviewed more than 150 current or former Executive Branch officials (the president, however, was not one of them; the White House declined to make him available) and reviewed reams of declassified documents. The result is a study of how Candidate Obama became President Obama on national security issues, and the prosecution of the global war on terror, in particular.

In a recent visit to “The Foxhole,” Savage said he began the book in 2013, after the leaks about National Security Agency operations by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. Those leaks, Savage said, “showed that Obama had really kept without much changes at all the expansive surveillance state that he had inherited from George W. Bush.” And the more Savage kept digging, the more frequently he uncovered evidence of this trend.

“This book has as its fundamental question that it's trying to answer: How is it that Barack Obama, the liberal law professor who was going to bring change from George W. Bush's global war on terrorism, and was such a strong critic of it on the campaign trail, ended up keeping so many parts of the counter-terrorism architecture that he inherited?

SAVAGE: He accepted indefinite detention without trial as legitimate. His plan to close Guantanamo, to move those people somewhere else and keep holding them under the same authority – he accepted the rendition to other countries based on diplomatic assurances, which on paper is the same policy as the Bush administration. He went beyond Bush in terms of the pace and intensity of drone strikes and targeted killings and, in fact, killed an American citizen without a trial, which is something that Bush never did….He presided over, as you know very well, an unprecedented crackdown on leaks and people who provide information to the public without authorization….And [he did this in] many other ways, absent torture, which kind of stands alone. He continued a lot of the policies that he had inherited, and this created a great disconnect from the expectations created by his campaign rhetoric.

One recurring strain in the Obama administration’s approach to national security that Savage identified was a “lawyerliness” that reflected the president’s own legal background and the large number of lawyers he surrounded himself with: Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton, John Kerry, among others. This led to a sometimes exhausting interagency back-and-forth, of the kind that lawyers love, but which could hamper swift implementation of policy; and, too, to a process-driven system that often arrived at the same place Messrs. Bush and Cheney had staked out, only using what Mr. Obama and his aides regarded as sounder legal vehicles to get there.

“Bush and Cheney were CEOs by nature, not lawyers,” Savage said. “And the result of this sort of overwhelming concentration of people who had been trained to think through the law school experience was they were prone to seeing the problem with Bush as being a rule of law problem.”

ROSEN: You point to this lawyerliness of the Obama administration. Did that serve the country well?

SAVAGE: So I think – well, first of all, you know, I'm always uncomfortable [with] normative questions. I think, though, that descriptively we can see, especially in comparing the sort of lawyerly Obama administration with the sort of remarkably un-lawyerly Bush administration…the Obama administration was deeply engaged with the law by nature. They wanted to ask the question. They wanted to know: How are we going to justify what we're doing as lawful?

ROSEN: […] Methodologically, I take issue with you here.

SAVAGE: OK.

ROSEN: You have covered this administration and you've done, in addition to your coverage of this administration, a ton of work on this book to put this book together. It's not fair to say that this book simply collects the work you had done as a daily deadline reporter.

SAVAGE: That's correct.

ROSEN: OK. And the book covers the first seven years, or first six years let's say, of the Obama presidency, correct?

SAVAGE: Up through about last August.

ROSEN: OK. So, in a sense, you are going from being a reporter to being a historian of sorts.

SAVAGE: I think I called it “investigative history.”

ROSEN: OK. And so one of the chief functions that we expect from the best of our historians is to render judgment, not simply to tell us what happened and why, but to say – but to provide judgment, and to say this was good, this was bad. This was – this served a good purpose, this didn't. And so when you demur in the aspect of me asking you whether this lawyerliness served the country well, you say, well, we can – we can be descriptive. You know, I'm putting you on the spot, assuredly, but I'm asking you to be the historian and tell us whether – which approach worked better, or –

SAVAGE: Well, I think, you know – I, I guess I reject the criticism because I think I identified a way in which it was positive and a way in which it was negative. So that's not purely, you know, not casting some judgment. But there's also the problem with [the fact that] we don't know where things are going. And this is the problem with writing anything you might call history, but it's really a sort of current events book. You know, what happened in this era may look very different twenty years from now in one way or another, depending on what happens next, or even what happens in Obama's last term.

As a member of President Obama’s war Cabinet, Hillary Clinton figures prominently in Power Wars, and possesses firsthand knowledge of much of its contents: the internecine struggles for control over national security decision-making that the book chronicles.

For the Republicans vying to succeed Mr. Obama, however, the book will be useful reading, for it offers clues to how the next commander-in-chief can adapt or reconfigure the national security apparatus to reflect his or her own preferences in the prosecution of the war on terror.

As Savage told me: “If Obama has some of these reforms…and then the next president decides ‘I disagree entirely,’ he can reopen that door entire[ly]….I think we can say with some confidence Donald Trump would be a very different kind of president – or even Marco Rubio.”