Key government witness testifies in Michael Sussmann trial

Fox News correspondent David Spunt has the details from Washington on ‘Special Report.’

"Making a false statement." What a nice, clean, uncomplicated world it would be for prosecutors, such as Justice Department Special Counsel John Durham, if that were the crime on the federal books.

All you’d have to do is prove that a person made a false statement. Like Democratic lawyer Michael Sussmann. He said he was not representing a client, when in fact he was representing the Clinton campaign. There’s no doubt he said it. There’s no doubt it wasn’t true. Case closed.

Except, down here on Planet Earth, it’s never that simple. The crime is not "making a false statement." It is making a false statement to the FBI.

SPECIAL COUNSEL JOHN DURHAM'S PROSECUTION OF MICHAEL SUSSMANN: EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW

That is not a small additional detail because the law further requires that the false statement be material. That is, the false statement cannot be about a trifling detail. It has to have made a difference to how the FBI evaluated the information in connection with its investigation. It has to have mattered.

This is a big problem for Durham. In Russiagate, it turns out that the FBI, was not the impartial, just-the-facts-ma’am investigator we expect it to be. At the headquarters level, the FBI had a rooting interest. It was invested in the proposition that Donald Trump was a corrupt, clandestine agent of Russia. And it wasn’t willing to drop the idea even if the evidence didn’t pan out.

That meant headquarters was willing to mislead its frontline agents.

Those agents diligently did their investigative work and determined that there was nothing to the allegation, made by Clinton lawyer Sussmann to FBI general counsel James Baker, that Trump and the Kremlin had established a communications back channel through a Trump email domain and servers at Russia’s Alfa Bank. But headquarters wouldn’t take "no" for an answer, and wouldn’t share basic facts that would have shown how unreliable the allegation was.

Hence the problem for Durham: How does he prove that Sussmann’s false statement mattered when the agents were also being misled by their own bosses?

This week, we were treated to the startling revelation that the FBI’s "EC" – the electronic communication by which the bureau formally opens investigations – contained a false statement, claiming that the predicate for the probe was information referred to the bureau by "the US DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE." Of course, the information came from Sussmann, not the Justice Department.

How could a false statement get into a critical FBI document … in a false-statement case? Embarrassingly, none of the FBI officials who’ve been asked about it, including the agents who drafted the EC, has been able – or at least willing – to answer that question. But we know the gist of how it must have happened.

Baker, the FBI general counsel who took the information (internet data and white-paper analyses) from Sussmann, immediately alerted his chain of command – FBI Director James Comey, Deputy Director Andrew McCabe, and counterintelligence agent Bill Priestap. Whatever happened in those consultations, headquarters made a decision to treat Sussmann as if he were a confidential informant, and thus to conceal his identity from the agents who would be tasked to assess Sussmann’s information.

Why did they do that? Baker suggested that it was to protect Sussmann. But there is no indication that Sussmann asked for his identity to be concealed from Bureau investigators – he came to the FBI quite intentionally. There was no threat to him from publicity – he was part of a Hillary Clinton campaign effort that wanted the information to go public.

General view of the J. Edgar Hoover F.B.I. Building in Washington, U.S., March 10, 2019. REUTERS/Mary F. Calvert (REUTERS/Mary F. Calvert)

Baker rationalized that Sussmann’s identity should be shielded from professional investigators because Baker believed Sussmann’s story about coming to the Bureau strictly as a patriotic American, not as a lawyer representing a client.

Call me cynical, but I’m not buying it. The FBI was not protecting Sussmann. The FBI was protecting itself – guarding its reputation, which has been the top headquarters priority throughout the agency’s history.

The FBI had already bought into the Trump-Russia collusion narrative. Even as Baker met with Sussmann, the Bureau was preparing to seek surveillance warrants from the FISA court based on the Steele dossier – another compendium of bogus anti-Trump information sourced to the Clinton campaign.

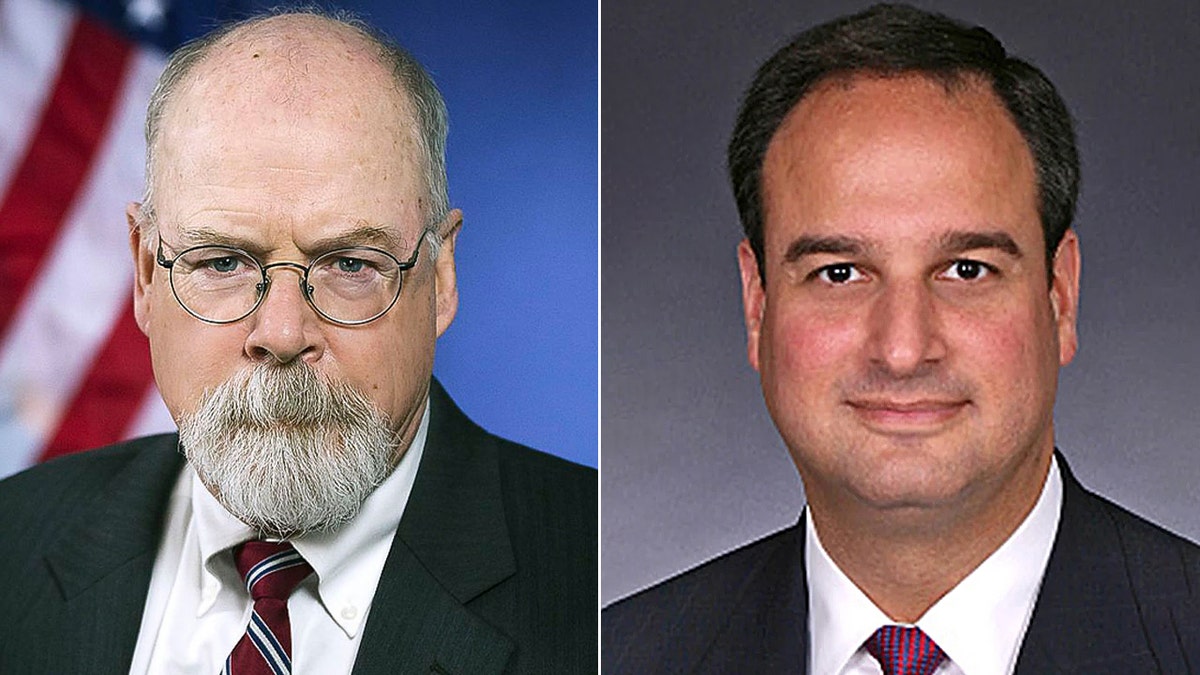

John Durham and Michael Sussmann. (US government/Perkins Coie)

Baker was not a babe in the woods. He knew Sussmann represented top Democrats – Sussmann had been the DNC’s lawyer when its servers got hacked. Baker and his bosses knew the FBI was taking a big risk accepting derogatory information about Trump about six weeks before Election Day from a top Democratic Party lawyer who refused to say who had given it to him.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

Knowing they were playing with fire, headquarters officials hedged their bets. They uncritically accepted Sussmann’s dubious story that he wasn’t representing a client and rationalized treating him as a confidential informant. But it wasn’t to protect Sussmann’s safety; it was to avoid leaving a paper trail identifying him. It was to avoid recording that headquarters had accepted anti-Trump opposition research from a highly partisan source in the stretch-run of a presidential campaign.

This concealment of Sussmann’s identity caused confusion and frustration for the Chicago cyber-crime agents who were called on to assess the information. Whatever headquarters told the field, the message got garbled (or worse) into a claim that the information came from the Justice Department. Headquarters would not tell them the source, a rudimentary piece of information that any investigator would want for purposes of assessing reliability.

The entrance signage for the United States Department of Justice Building in Washington DC, USA. The Department of Justice, the U.S. law enforcement and administration of Justice government agency. (iStock)

And even when the agents concluded the data provided by "the Justice Department" was deeply flawed, headquarters would not permit the investigation to be shut down. Unable to establish a cyber crime, Chicago agents were told they had to open a counterintelligence investigation because "People on 7th floor to include Director are fired up about this server," as agent Joe Pientka, assigned to headquarters and deeply involved in the Trump-Russia investigation, put it.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The 7th floor, FBI headquarters, has given Sussmann his defense: Sussmann didn’t lie to the FBI investigators; their headquarters lied to them. Susmman may have misled Baker in claiming not to represent a client, but Baker wasn’t fooled – headquarters officials fully understood the political nature of the information; that’s precisely why they concealed it from the agents doing the actual investigating. And in the end, what did it matter? After all, even when the information turned out to be nonsense, the FBI nevertheless continued pursuing the Trump-Russia collusion narrative.

Durham has banked his case on the premise that the FBI was a dupe rather than a willing, though cagey participant in the Russiagate farce. That turns what looks like a slam-dunk false statement into a very tough case for prosecutors.