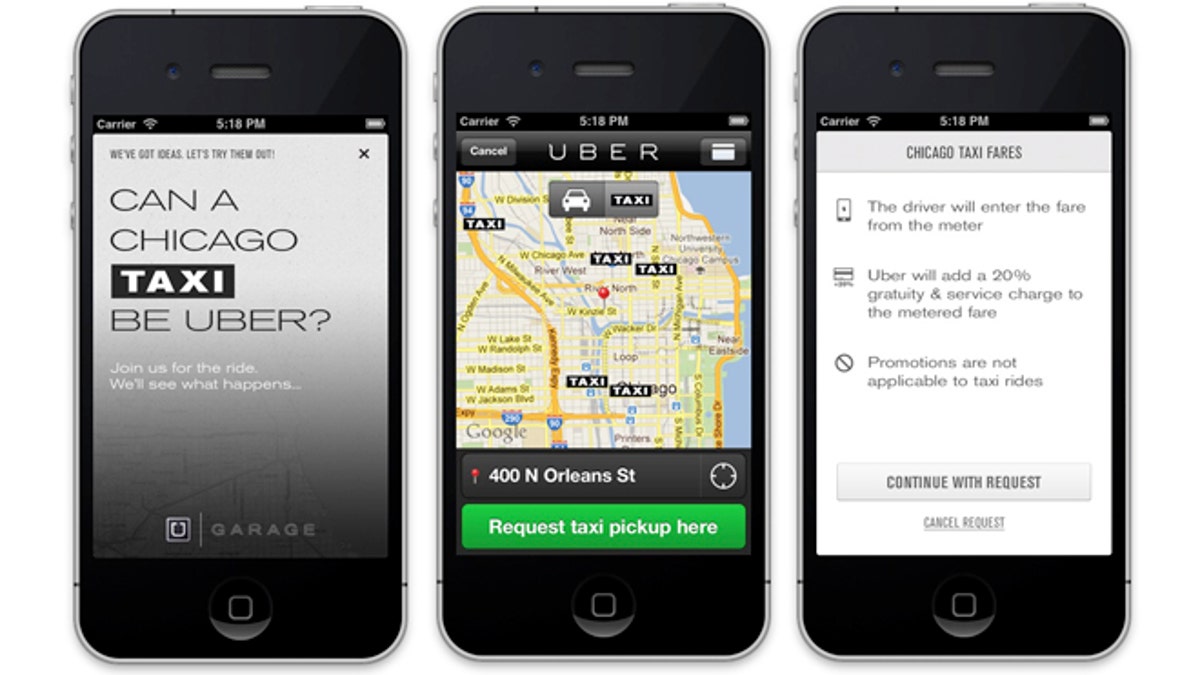

Innovative app Uber allows you to hail a taxi from your smartphone. The company recently expanded to Chicago, but still faces numerous regulatory hurdles. (Uber)

If you saw a fat man in a sleigh distributing presents this week, he was in violation of several government regulations.

The Federal Aviation Administration has complaints about his secret flight path. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources might shoot his unauthorized reindeer the way they shot a baby deer named Giggles at an animal shelter this year. His bag of gifts definitely violates numerous charity tax rules.

In real life, government barely lets people give each other rides in cars. But now the Internet has given birth to some exciting new businesses that challenge this conceit.

[pullquote]

Companies called Lyft, Uber and Sidecar offer a phone app that allows people who need a ride somewhere to connect to a driver nearby who'd like to make a few extra bucks. It's like creating an instant taxi business -- which is why it makes existing taxi businesses nervous.

I became a Lyft driver. Once I passed a criminal background check and got my Lyft driver app, I pressed a button on my phone saying I was "available." I quickly got a message from someone nearby who wanted a ride.

My passenger was easy to find -- my phone gave me directions. He wanted to go to a grocery store. After I dropped him off, I told my phone app I was "available" again. No cash changed hands.

My passenger's phone suggested he give me a credit card "donation" based on time and distance. He could have stiffed me, but if he did, it would appear on his Lyft "rating," and he'd have trouble getting another ride.

My next passenger was a woman. Why would she feel safe getting into a stranger's car? Again, the rating system protects both her and me. Her phone showed her my picture and ratings from other passengers (with me, she took a chance, as I was a new driver).

Because of the ratings, both passengers and drivers have an incentive to behave well. The higher your rating, the easier it is to get or give rides.

In the end, I made money, and my passengers saved money (Lyft rides are about 20 percent cheaper than taxis). Win-win!

But regulators and taxi companies don't see it that way.

Taxi companies aren't happy about losing business to people like me, driving my own car. One cabbie complained, "We have to pay big money for licenses, get fingerprinted, have commercial insurance. [Lyft] has nothing! Sidecar has nothing!"

But it's not "nothing." I had to have a driver's license, a state-inspected car and there was that background check. But more useful than all that: the ratings.

This instant feedback gives drivers and customers more reliable information than piles of licensing paperwork spewed out by regulatory agencies.

Do you pick a contractor or dentist after examining their licenses? No, you consult friends or websites like Yelp to determine the sellers' reputation. Feedback from customers is more useful than any bureaucrat's stamp of approval.

Internet apps like Lyft's make this feedback ever better.

Will government crush innovations like Lyft? Maybe.

Seattle moved to limit it.

Nashville declared it illegal to charge anything less than $45 for rides, so there's no way for a company like Lyft to compete by undercutting regular cabs' prices.

Regulators want their fingers in everything. A new idea gives them an excuse to draw attention to themselves as "consumer protectors." In addition, existing taxi companies request regulation. They want politicians to regulate new competition out of existence.

Luckily, technology and capitalist innovation sometimes move faster than the lazy dinosaur that is government. Lyft, Uber and Sidecar have quickly become popular, and this may help them avoid being crushed.

By contrast, politicians don't hesitate to destroy things that people think of as weird or dangerous.

Ride-share companies, perhaps sensing that it's better to ask for forgiveness than permission, offered rides without first seeking approval from every regulator. Now they have millions of customers.

Politicians often fear regulating things that are widely liked.

Government is as crude and annoying as a speed bump, but individuals looking for better ways to do things keep cruising ahead. Sooner or later, if we restrain the regulators, the market might even produce flying sleighs.